The Wreck of the Schooner Charles

Third in a series of Occasional Papers about Eastern Cemetery in Portland, Maine

by Ron Romano

© 2017

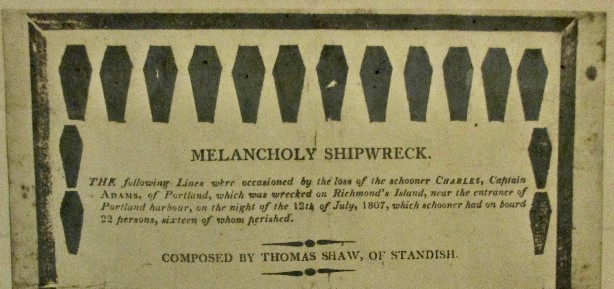

Figure 0.

Detail from a broadside published 1807 (Collections of Maine Historical Society)

- MELANCHOLY SHIPWRECK. THE following Lines were occasioned by the loss of the schooner CHARLES, Captain ADAMS, of Portland, which was wrecked on Richmond’s Island, near the entrance of Portland harbour, on the night of the 12th of July, 1807, which schooner had on board 22 persons, sixteen of whom perished. COMPOSED BY THOMAS SHAW, OF STANDISH

July the twelfth they did set sail,

From Boston port with fav’ring gale,

And then to Portland made their way,

Upon God’s holy sabbath day.

When night came on, and all at ease,

The vessel gliding o’er the seas,

They did not think, they did not fear,

The awful danger which was near.

[From “Melancholy Shipwreck” by Thomas Shaw, July 14, 1807]

Contents

- Introduction

- 1 & 2: Captain Jacob Adams & Mrs. Dorcas (Davis) Adams

- 3: Ship’s Mate Mr. Williams

- 4: Seaman (Thomas) Tandy

- 5: Eben Ruby, the ship’s cook

- 6: Thomas Phillips, the cabin boy

- 7, 8 & 9: Sidney Thaxter, Mr. Cook, & Mr. Moonie

- 10: Mr. Pote

- 11, 12, 13, 14 & 15: The Richards Family

- 16: Eleazer Alley Jenks

- 17: Mrs. (perhaps Miss) White

- 18, 19 & 20: Three generations — Mrs. Stonehouse, Mrs. Hayden, & infant Robert Hayden

- 21: Nathaniel Sargent

- 22: Lydia Carver

- Summary

- Sources

Introduction

In the summer of 1807 during a routine journey from Boston to Portland, the schooner Charles crashed off Cape Elizabeth, Maine just after midnight. The ship was carrying 22 people and cargo valued at $25,000. Sixteen people lost their lives. The task of creating grave markers for the victims fell onto the shoulders of the area’s resident stone- cutter, Bartlett Adams (1776–1828). Bartlett’s shop made at least four gravestones honoring six of the victims. The story of the wreck was told in a chapter in my book, “Early Gravestones in Southern Maine...” (History Press, 2016). This paper presents the research conducted for that chapter and provides additional information about the crew and passengers involved.

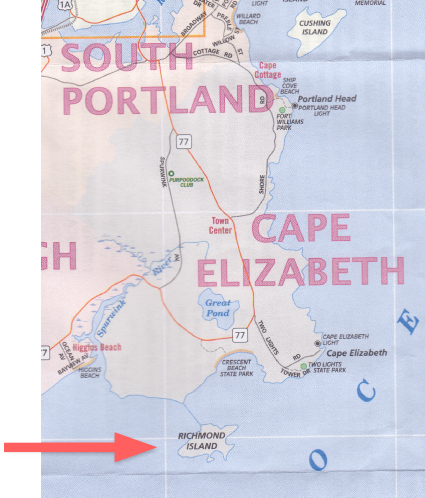

Figure 1.

Richmond (sometimes Richmond’s) Island, the site of the wreck. AAA map detail

1 & 2: Captain Jacob Adams & Mrs. Dorcas (Davis) Adams

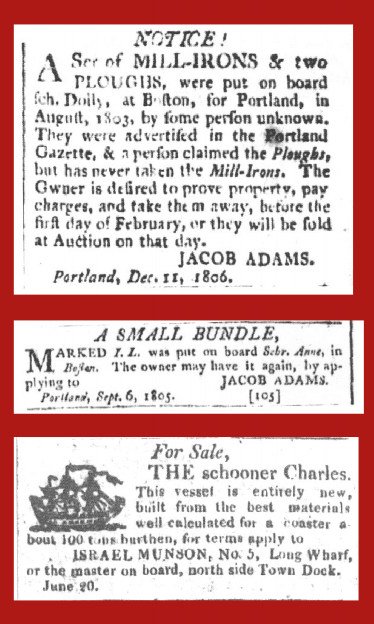

The Captain of the Charles, Jacob Adams, was a native of Maine, born in Portland in 1772. While both he and stone-cutter Bartlett Adams shared a name and ran their businesses out of Portland, the two were not related. Captain Adams owned and operated a packet ship, ferrying people and cargo regularly between Portland and Boston. Before the Charles, he had sailed at least two other packet ships running the Portland-to-Boston route. In the summer of 1803, his boat was the schooner Dolly, as shown in an advertisement (Figure 2, top) he placed in the Portland Weekly Eastern Argus.

By the fall of 1805, his ran the schooner Anne, as shown in an ad in the Argus on September 6 of that year (Figure 2, center).

An advertisement from the Boston Repertory on June 20, 1806, brought Captain Adams and the schooner Charles together (Figure 2, bottom).

Jacob Adams and Dorcas Davis (born 1775), also of Portland, married on October 12, 1794. Officiating was Justice of the Peace, John Colby. Their marriage record gives the Captain’s name as “Addams,” the only record found with that spelling. Five children followed, beginning in 1795. According to Andrew Adams’ genealogy of the Adams clan, the children were:

- Sally (Sarah), born January 18, 1795. She married Matthew Cobb (b. 1796) in 1818 and died in 1870. Matthew predeceased her by five years. They were buried in a family lot in Portland’s Western Cemetery.

- Miriam, born in Portland (date unknown). She married Nathaniel Roberts (b. 1796) in 1816. She predeceased her husband, passing in 1859; Nathaniel lived ten years longer, passing in 1869. They too were buried in their own family lot at Western Cemetery.

- William, born in Portland (date unknown)

- George, born in Portland (date unknown)

- A son, born in Portland (but name and date unknown).

Figure 2.

- [top] NOTICE! A Set of MILL-IRONS & two PLOUGHS, were put on board sch. Dolly, at Boston, for Portland, in August, 1803, by some person unknown. They were advertised in the Portland Gazette, & a person claimed the Ploughs, but has never taken the Mill-Irons. The Owner is desired to prove property, pay charges, and take them away, before the first day of February, or they will be sold at Auction on that day. JACOB ADAMS. Portland, Dec. 11, 1806.

[middle] A SMALL BUNDLE, Marked I. L., was put on board Schr. Anne, in Boston. The owner may have it again, by applying to JACOB ADAMS. Portland, Sept. 6, 1805. [105]

[bottom] For Sale, THE schooner Charles. This vessel is entirely new, built from the best materials, well calculated for a coaster about 100 tons burthen, for terms apply to ISRAEL MUNSON, No. 5, Long Wharf, or the master on board, north side Town Dock. June 20.

The family genealogy also notes that following the tragedy at sea, the orphaned kids were raised by their uncle (Jacob’s younger brother), Benjamin Watson Adams and his wife Elizabeth Varney, in Windham, Maine. Very few good records are found for this family, but the three boys are said to have all gone to sea and died young.

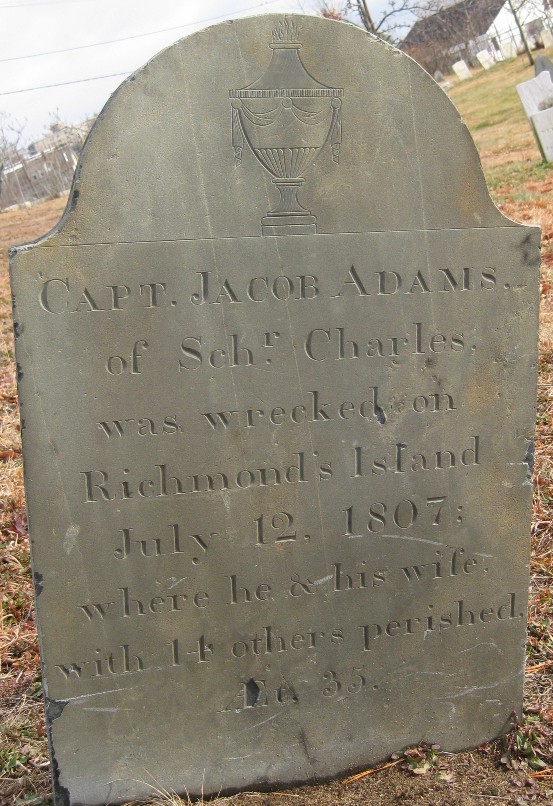

The fateful journey back to Maine began in Boston at 7:00 AM Sunday, July 12, and was expected to take all day and into the night, depending on sea and weather conditions. The Charles passed Boon Island around sunset. When the ship slammed into Watt’s Ledge off Richmond Island about midnight, Captain Adams and three other men were able to swim from the ledge to the safety of the island beach. The sea was stormy and there was no visibility, given the hour. But the Captain could hear the wails of his wife and other survivors still trapped on the wreck and made a heroic effort to rescue them. He swam back to the ledge and tried for an hour to get back on board the wreck to save them. Unfortunately, the tide was rising and a wave washed him off the ledge to his death. He was 35 years old. His body was among the first three recovered early Monday, July 13; the body of his wife Dorcas (age 32) was never found.

The Captain’s remains were brought to Rev. Elijah Kellogg’s meeting house of the Second Parish in Portland, where a funeral service was held on the afternoon of Tuesday, July 14, attended by a great crowd. His burial at Eastern Cemetery followed the service. The grave marker created for Captain Adams and his wife was carved by Alpheus Cary (Figure 3), who was working in the shop of Bartlett Adams at the time. Cary was an accomplished carver who would move to Boston and have a successful stone-cutting career of his own. The stone he made for Captain and Mrs. Adams features a finely-rendered urn decorated with a bunting and shows his ability to finely letter and number slate gravestones.

Figure 3.

- CAPT. JACOB ADAMS, of Sch’r Charles, was wrecked on Richmond’s Island July 12, 1807: where he & his wife, with 14 others perished, AEt. 35.

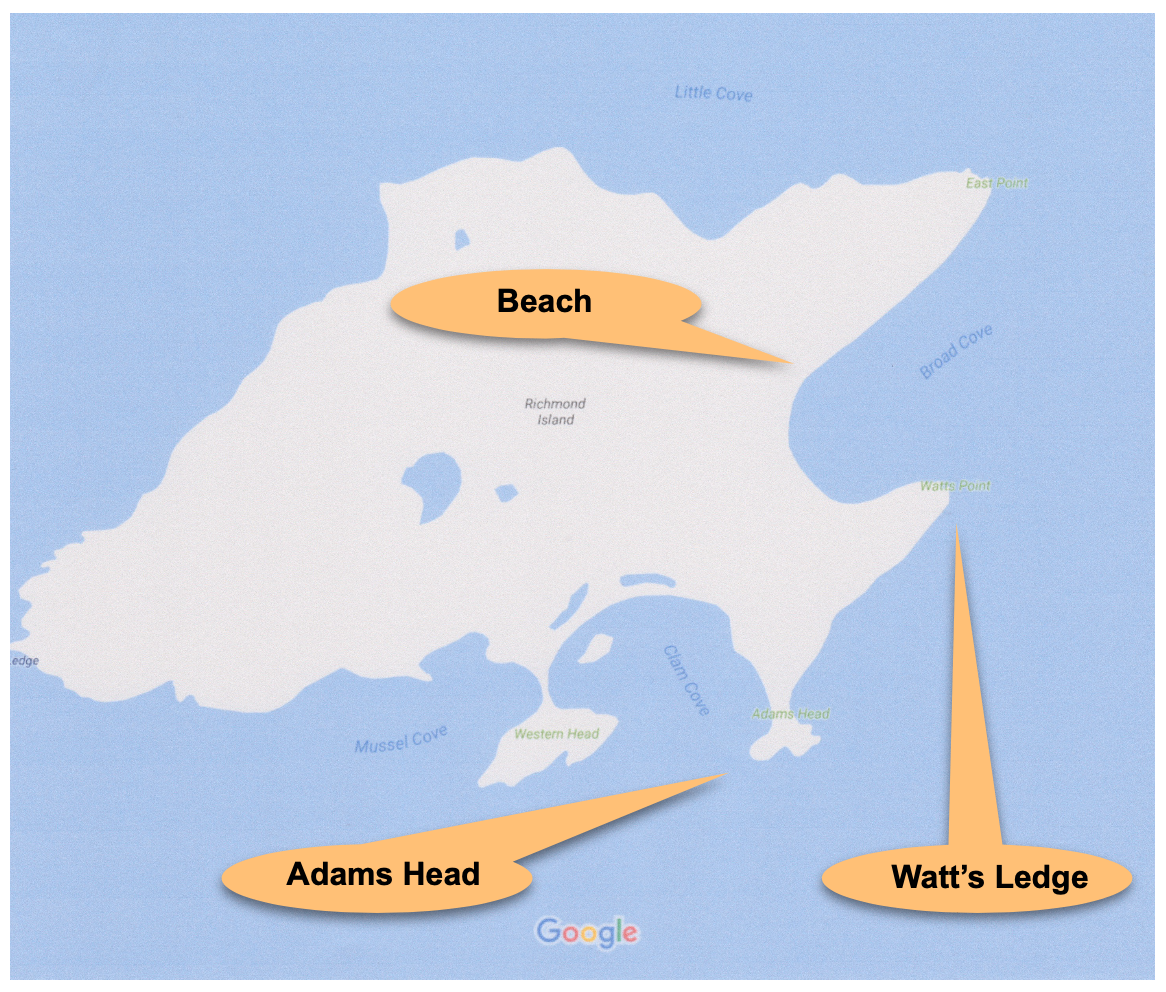

Andrew Adams’ family genealogy, published 93 years after the wreck, noted that Captain Adams’ life had also been honored in that “the place where the vessel struck is now known as Adams’ Head.” Modern-day maps show both Adam’s Head and the adjacent Watt’s Ledge along the south shore of Richmond Island (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

3: Ship's Mate Mr. Williams

Given that Captain Adams’ Mate, Mr. Williams, was one of the fortunate six who survived the wreck, it’s odd that his first name was not recorded. All newspaper reports and other writings of this tragedy simply refer to him as “Mr. Williams.”

As ship’s mate, he was the Captain’s right-hand man; in fact, the Captain had called upon Mr. Williams to help him navigate through the dense fog they’d encountered as they neared Portland. He sent Williams forward, and when Williams heard waves crashing just ahead of them, he realized how dangerously close to the shore they’d come. He raised an alarm but it was too late for the Charles, which moments later hit the rocky ledge.

Mr. Williams was trapped on the wreck all night, and was one of only three men rescued from the wreck itself (three others were rescued from Richmond Island beach). He was the last of the survivors to be picked up and brought to shore Monday morning, when—shortly after 9:00 AM—a gentleman from Cape Elizabeth named Maxwell, who’d sailed over to the island to assist, came to his rescue.

4: Seaman (Thomas) Tandy

Mr. Tandy was one of five members of the crew of the Charles, the others being the Captain, First Mate Williams, a cook, and a cabin boy. All reports of the incident refer to the seaman only as “Mr. Tandy.” But from searches on Ancestry and other sources, I suspect he was Thomas Tandy. There is a marriage record for Thomas Tandy in Portland in 1804; his wife was Betsey Austin, also of Portland.

Little is known about Tandy other than the fact that he did not survive the disaster. The July 20 Portland Gazette noted that his body was “found and interred.” The likely place of interment was Eastern Cemetery, since four other people mentioned in that article—whose bodies were also “found and interred”—ended up in Eastern Cemetery, while the one victim who is known to have not been buried at Eastern Cemetery wasn't listed with Tandy and the others in that article.

Two other clues suggest Mr. Tandy was in fact Thomas Tandy. First, the 1810 US census for Portland lists a “head of household” named “Betsie Tandy,” being in the age range of 26 to 44. Women were not usually listed as heads of households unless they were widows. That census was three years after the shipwreck. Second, a marriage record is found for “Mrs. Betsey Tandy” in 1814, seven years after the wreck. Since the marriage record gives the bride’s name as “Mrs.” it’s a clear indication this was her second marriage.

While all of these clues strongly suggest the Seaman’s first name was Thomas, it remains unstated in the wide variety of the contemporary accounts of the shipwreck.

5: Eben Ruby, the ship’s cook

Eben (Ebenezer) Ruby, the only African-American aboard, was the ship’s cook. His family tree information is sparse so I could not find names of his parents or siblings, and the only clue to his age—and admittedly it is hardly helpful—is that one source referred to him as “young” at the time of his drowning in 1807. He married in Portland, as we have his marriage intention dated March 25, 1804, using the spelling of his name as “Rubee.” His wife was Matilda Chadwick, also of Portland. Perhaps they were in their late teens at the time of marriage? If so, his year of birth would be around 1788.

Good records do exist for an Eben Ruby of the next generation, being born 1816 to Samuel (1790–1857) and Margaret C. Ruby (1792–1885). This Eben married Jemima Pease in Portland in 1838 and census records from 1840 to 1870 follow them to New Gloucester, where they farmed and raised three children. Some census records list them as mulatto, others as free colored people. The 1880 directory for Lewiston, Maine, has Jemima as a widow of Eben, so he passed between 1870 and 1880.

Of course, there were more famous Rubys in Portland at the same time. Reuben Ruby (1799–1878) was a successful businessman, a leader in the anti-slavery movement, and one of the founders of the Abyssinian Church in Portland (which served the black community). His wife and son, Jannett and William, as well as his sister, Sophia Ruby Manuel, are buried at Eastern Cemetery. Reuben far outlived them all, and was buried at Forest City Cemetery in South Portland in 1878.

So, was the Eben Ruby who farmed in New Gloucester perhaps named for his uncle, the ship’s cook who had drowned nine years earlier? If so, could his father Samuel (born 1790) been an older brother of Reuben (born 1799) and/or ship’s cook Eben (assumed born circa 1788)? It opens a few possibilities for exactly how these folks are related, but certainly they were. It cannot just be coincidence that they were African-American, they shared the name Ruby, and they hailed from Portland.

However related to the others, ship’s cook Eben Ruby died the night of the wreck and his body was never recovered. Just two months following his drowning, his widow Matilda married William Johnson in Portland (Figure 5). The marriage record used “Rubey” and confirms that she was black. Census records that followed this couple from 1810 to 1830 further confirm that a family of four people of color lived in Portland under the name of William Johnson.

Figure 5.

- Form R-2 (For old records only)

Copy of an Old Record of a Marriage.

Groom: William Johnson

Bride: Matilda Rubey

Residence of Groom: Portland

Residence of Bride: Portland

Color of Groom: Black

Color of Bride: Black

Intention Filed: Aug. 23, 1807

By whom Married: Rev. Samuel Deane

Residence: Portland

Official Station (Clergyman, Justice of the Peace, etc.): Clergyman

Date of Marriage: Sept. 7, 1807

Place: Portland

6: Thomas Phillips, the cabin boy

Thomas Phillips was Captain Adams’ cabin boy, so he would have been assigned whatever duties the Captain required to keep his business afloat. We don’t know Thomas’ age, although cabin boys were typically 13 to 15 years of age. We also don't know where he was from or the identity of his parents parents or siblings.

As the waves pounded at the broken ship through the night, survivors clung to the wreckage as best they could, but one by one, through sheer fatigue or inability to withstand the waves, they slipped into the sea. Thomas was able to find a place of safety and survived the night. Monday morning, people along the shore of Cape Elizabeth realized that the ship had wrecked, and rescue boats were set off from the mainland to look for survivors.

Boats reached the ledge between 8:00 and 9:00 AM. Thomas attempted to get aboard one, but was unable to do so. As his potential rescuers watched helplessly from their boats, Thomas went under and was washed out to sea to his watery grave.

7, 8 & 9: Sidney Thaxter, Mr. Cook, & Mr. Moonie

Three men were rescued from the beach at Richmond Island. Soon after the Charles crashed, passenger Sidney Thaxter leapt into the water and then made his way onto the ledge. He found a flat spot on the rocks and in an effort to save the people aboard dragged a plank from the ship to the rocks. Passengers Cook and Moonie (Monie in some accounts) were able to navigate the plank to the safety of the ledge. Captain Adams was next. The four men thought that they could wade ashore to Richmond Island beach, but found the water was too deep. In the dark, with the sea roaring around them, Thaxter, Cook, and Moonie swam towards the sound of the waves crashing on the beach some 30 feet away. Once they made it to the safety of the beach, they called out to the Captain to join them. Adams, a strong swimmer, successfully made the trip. But upon reaching the shore, he heard the shrieks of his wife and others still trapped. He told the trio that he would return to the wreck and rescue the survivors, “or die trying.”

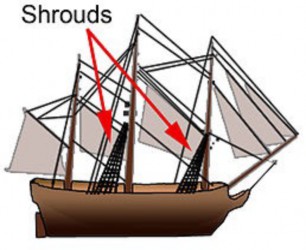

Thaxter, Cook, and Moonie were found in good condition Monday morning, their rescuers returning them to Portland by about 9:00 AM. Once safely on the mainland, Sidney Thaxter reported that when he had left the wreck for the ledge, “there were six persons holding fast on the shrouds (Figure 6), four men, one woman, and a boy.” The boy was, no doubt, cabin boy Thomas Phillips, the 16th—and last—to die in the tragedy.

Figure 6.

First names, ages, and family information are not found for Mr. Cook or Mr. Moonie. Sidney Thaxter is an unusual enough name, so some information was found that could be his. There is a record of the birth of a Sidney Thaxter in Hingham, Massachusetts, in 1788. The 1820 census has a Sidney Thaxter, age between 26 and 44, living in Gray, Maine. If the Hingham man is our Sidney Thaxter, he would have been 19 at the time of the wreck, and 32 at the time of the 1820 census.

10: Mr. Pote

Mr. Pote was another of the three men rescued from the ship on Monday morning (First Mate Williams addressed above and Mr. Richards just below being the other two). Recall that upon rescue from the island, Sidney Thaxter had reported “four men holding fast on the shrouds;” Mr. Pote was one of those men. The newspaper reported that the three taken from the wreck were found, “...exhausted with fatigue, & almost disabled with many bruises. The fragments of the vessel, the feattered (sic.) remains of the cargo & the lifeless bodies of the deceased, entangled in the shrouds, or dashed among the rocks, formed a dreadful scene of desolation—a spectacle of horror shocking to humanity.”

Portland census records before and after the disaster give us a few possibilities for a first name for Mr. Pote. Gamaliel, Increase, Samuel, and Charles were all named Pote and were heads of households in Portland in one or both of the censuses for 1800 and 1810. I also found record that a “Jeremy Pote of Portland” had published a document in 1798; that record was coincidentally listed in the same cluster of documents published by Eleazer Alley Jenks (see #16 below). It could be the two men knew one another and were traveling home together from Boston.

11, 12, 13, 14 & 15: The Richards Family

Samuel Richards lived in Portland. He was married and had two children at the time of the tragedy. All were aboard the Charles. His unmarried sister, from Dedham, Massachusetts, was traveling with them on the Boston-to-Portland packet. With Williams and Pote, he was rescued from the wreck on Monday morning. Though his life was spared, his loss was great; his wife and children, as well as his sister, drowned. Of the four family members he’d lost, only one child’s body was recovered and was likely buried at Eastern Cemetery. His wife, child, and sister were all lost at sea.

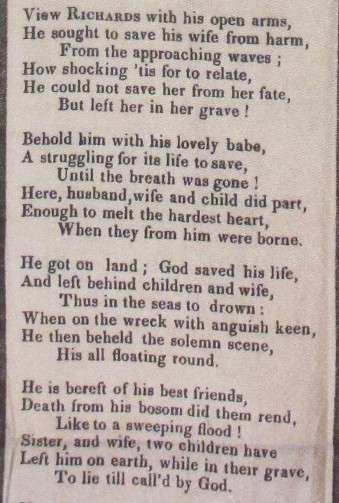

Very soon after the newspaper reports of the incident, Ebenezer Robbins published “An Elegy” (its full title being, “An Elegy on the Distressing Scene of the Schooner Charles”) to honor the tragedy and the great loss of life. An original copy of the work, printed on silk, is found in the Portland Room collections at the Portland Public Library. Robbins wrote 64 stanzas, 384 lines in total, of rhyming verse. Some verses he wrote regarding the Richards family are found in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Detail from “An Elegy” by Ebenezer Robbins

- View RICHARDS with his open arms, He sought to save his wife from harm, From the approaching waves; How shocking ’tis for to relate, He could not save her from her fate, But left her in her grave!

Behold him with his lovely babe, A struggling for its life to save, Until the breath was gone! Here, husband, wife and child did part, Enough to melt the hardest heart, When they from him were borne.

He got on land; God saved his life, And left behind children and wife, Thus in the seas to drown; When on the week with anguish keen, He then beheld the solemn scene, His all floating round.

He is bereft of his best friends, Death from his bosom did them rend, Like to a sweeping flood! Sister, and wife, two children have Left him on earth, while in their grave, To lie till call’d by God.

The names and ages of Samuel Richards’ wife and children have eluded discovery. References to the family simply refer to his wife as “Mrs. Richards” and the children are neither named nor assigned ages. One Samuel Richards married Rebecca Badger in Portland in 1804. If this is our couple, they certainly could have had two children by July 1807, although all accounts of the incident refer to them as “children” rather than “babies” or “infants.” The words used in the newspaper accounts may not have been intended to suggest ages, but it’s interesting to note that one other child from another family that drowned, aged 10 months, is referred to as a “baby” in one account. Still, we don't have hard evidence that Samuel Richards’ children were older.

Samuel Richards may have remarried. Vital records in Portland include two possibilities: A marriage between Samuel Richards and Molly Hearl on January 31, 1808, and a marriage between Samuel Richards and Rebecca Wallis (or Willis) on November 25, 1808. Census records are not reliable in tracking his life following the tragedy.

16: Eleazer Alley Jenks

The most prominent citizen among the passengers of the Charles was Eleazer Alley Jenks, born May 18, 1776 in Portland. His father was a Revolutionary War veteran, Moses Jenks. Eleazer (sometimes Elezer) learned the printing trade as a young man and in 1798 at just 22 years old founded the Portland Gazette, a newspaper which appeared over the subsequent years using a few different titles. About a year before the wreck, he transferred ownership of the Gazette to Isaac Adams (yet another Adams, but not related to either Bartlett or Captain Jacob). Jenks’ printing business also produced almanacs, sermons, eulogies, and other public documents. In 1801 he married Clarina Parsons Greenleaf at her family’s home in New Gloucester, Maine. The couple settled in Portland and had three children: Elizabeth (born 1802), Alexander Hamilton (born 1804) and Eleazer Alley Jr. (born 1806).

The violence of the sea was relentless. As the ship crashed into the ledge, it was turned 90- degrees, so the deck was perpendicular to the surface of the water, tossing cargo and passengers into the ocean. Through the night the crashing waves continued to break the ship into pieces and pull people into the water to their deaths. Eleazer Jenks found temporary safety by tying himself into the shrouds of the ship. He was one of the men Sidney Thaxter had referred to when he noted to his rescuers that people were clinging to the ship’s rigging. But when rescuers arrived after daylight, they found the lifeless body of 31-year-old Jenks, who had “lashed himself to the shrouds, but died in that position and was found hanging to them.”

17: Mrs. (perhaps Miss) White

One of the least well known passengers aboard the Charles was a woman named White. In some accounts she is referred to as “Mrs.,” in others she is listed as “Miss.” So we know nothing of her but that she was among the casualties of the wreck, and that her body was one of the first three found Monday morning. The funeral service held at the Second Parish Meeting House on Tuesday, July 14, honored the Captain, Mrs./Miss White, and one other woman discussed below. The Meeting House was crowded with townspeople who then accompanied the bodies to the cemetery for burial. Though we have no grave marker or burial record for confirmation that she is there, surely Mrs./Miss White lies at Eastern Cemetery with the two others who were mourned that day and whose grave markers can be still found there today.

18, 19 & 20: Three generations – Mrs. Stonehouse, Mrs. Hayden, & infant Robert Hayden

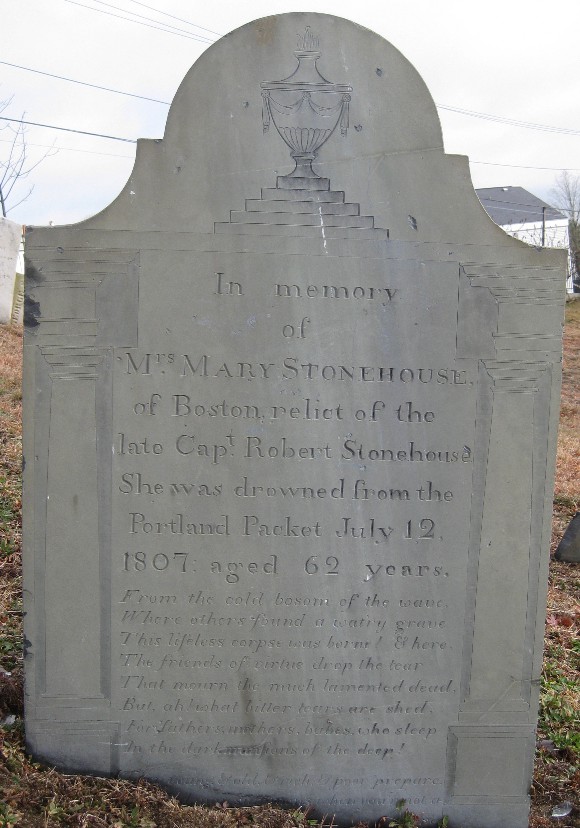

The finest surviving grave marker for the victims of the wreck is for Mrs. Mary (Rhea) Stonehouse, widow of the late Captain Robert Stonehouse, who had died three years earlier, at age 63. He is likely buried in Boston, although no interment record is found to confirm this. Mrs. Stonehouse’s marker is quite large and inscribed with an extensive epitaph. Her marker has an extraordinary 400+ letters and would have taken a week or more for Alpheus Cary to hand carve. The inscription on the stone is framed by two large columns, symbolizing her passage from the familiar world to the unknown. An urn on a stepped base decorates the tympanum (or top) of the stone.

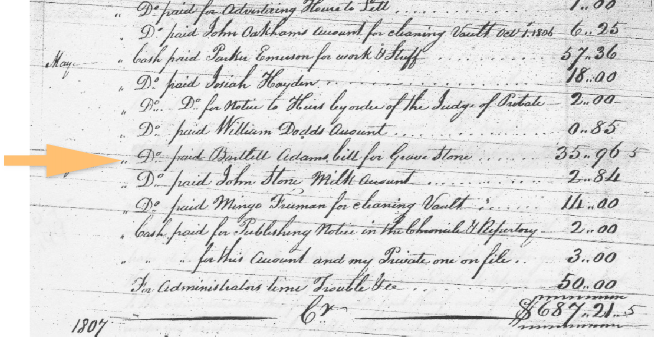

A probate record is located in Boston for Mrs. Stonehouse and shows that Bartlett Adams was paid $35.96 for this marker. While this is a hefty sum in 1807, it reflects the value of the stone’s unusually long epitaph, requiring a great deal of time to complete, and signifies that she was a woman of wealth.

Figure 8.

Detail of Mary Stonehouse’s marker

Figure 9.

- In memory of

Mrs. MARY STONEHOUSE,

of Boston, relict of the

late Capt. Robert Stonehouse.

She was drowned from the

Portland Packet July 12,

1807; aged 62 years.

From the cold bosom of the wave

Where others found a watery grave,

This lifeless corpse was borne! & here

The friends of virtue drop the tear

That mourn the much lamented dead,

But, ah! what bitter tears are shed,

For’fathers, mothers, babes, who sleep

in the dark mansions of the deep!

Figure 10.

Probate record for Mary Stonehouse, showing payment to Bartlett Adams

- " Do paid for advertising House to Sell 7.00

" Do paid John Oakham amount for cleaning vault Oct. 1, 1806 6.25

May " Cash paid Parker Emerson for work [and stuff] 57.36

" Do paid Josiah Hayden 18.00 " Do Do paid for notice to [this] by order of the judge of probate 2.00

" Do paid William Dodds amount .85

" Do paid Bartlett Adams bill for Grave Stone 35.96 5

" Do paid John Stone Milk amount 2.86

" Do paid Mingo Freeman for cleaning vault 11.00

" Cash paid for publishing notice in the Chronical Reperatory 2.00

" " " for this amount and my Private one on file 3.00

For administrator's time trouble etc. 50.00

1807 Cr $687.21 5

Mary Rhea married Robert Stonehouse in Boston in 1766. The marriage was conducted by Reverend Samuel Mather, one of the sons of the more famous Cotton Mather. A record from 1778 comes from the journal of Samuel Tucker, a Commodore in the American Revolution. While at sea, he and Captain Stonehouse crossed paths. Tucker’s journal notes on September 27, 1778: “At 11 A.M. came up and spoke with the brig William, Captain Robert Stonehouse, who sailed from Boston for Amsterdam the 10th day of March, 1778, with a cargo of twenty casks tobacco, one hundred and ninety casks flax-seed, fifty barrels pot and pearl ash. Sailed from Amsterdam, August 3, 1778; out 50 days when spoke with.”

Few other family records are found for Robert and Mary, so it’s unclear if their daughter, Eliza, was an only child. Eliza was born around 1786, probably in Boston. We next find a marriage record for her in Boston, on November 30, 1805, to Josiah Hayden. Hayden was a Massachusetts native, born in 1781. But he had relocated to Portland and owned a shoe store in the bustling town, as seen in the newspaper advertisement (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

- A New Shoe Store.

JOSIAH HAYDEN, respectfully informs the public, the Ladies and Gentlemen of Portland in particular, that he has taken the Store lately improved by Mr. WILLIAM MOULTON, a few doors east of the Columbian Tavern, and opposite Messrs. Z. HANNAFORD & CO. Middle-Street—

Where he has for Sale,

A General Assortment of Ladies’, Gentlemen’s and Children’s SHOES,

of every description, on such terms as to make it worthy the attention of purchasers. As his Shoes are particularly made for retailing, they will be warranted to be of the first quality.

105

Sept. 6

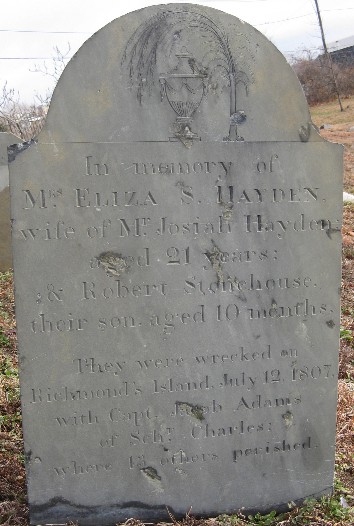

Within a year of their marriage, Josiah and Eliza welcomed their first child, Robert Stonehouse Hayden, on September 19, 1806. Naming their son must have come easily to the young couple, as both Josiah and Eliza’s fathers were named Robert.

Figure 12.

- In memory of

Mrs. ELIZA S. HAYDEN,

wife of Mr. Josiah Hayden,

aged 21 years:

& Robert Stonehouse,

their son, aged 10 months.

They were wrecked on

Richmond’s Island July 12, 1807,

with Capt. Jacob Adams

of Sch’r Charles:

where 13 others perished.

It’s easy to imagine this scenario: Josiah was too busy running his business in Portland to accompany his wife and infant son on perhaps their first journey together to visit Mrs. Stonehouse in Boston. Mary Stonehouse had then decided to come back to Maine to visit a while with her daughter and grandson. But regardless of the reason Josiah Hayden didn't make the journey, it spared him his life, as his wife, child and mother-in-law all lost theirs in the wreck of the Charles.

None of these three were lost at sea; their bodies were recovered and interred at Eastern Cemetery. Eliza Hayden’s remains were among the first three found, so it was she who was honored with Captain Adams and Mrs./Miss White on Tuesday, July 14. The bodies of Mary Stonehouse and her grandson Robert Hayden were found within a day. The Eastern Argus report of Thursday, July 16 noted that Mrs. Stonehouse had already been interred (on Wednesday the 15th) and that, “Mr. Hayden’s child will be interred at 4 o’clock this afternoon—the friends and relations are requested to attend.”

Just downslope from Mary Stonehouse’s marker is the gravestone shared by her 21-year-old daughter Eliza and 10-month-old grandson Robert. It’s the third slate marker that was carved by Alpheus Cary for the victims of this tragedy. Just two rows west from them is the grave of the Captain. It is very likely true that the graves of Mr. Tandy,the Richards child, Mr. Jenks, and Mrs./Miss White are all within this same area. Perhaps one day during conservation activities, we will be fortunate enough to unearth one (or more!) of their stones and restore them for all to see.

Josiah Hayden remarried a year after the disaster. He and his second wife, Dorcas Tobey, had nearly five decades together, mostly back in Massachusetts. Josiah died in Boston of consumption, at age 75, in 1856.

21: Nathaniel Sargent

The newspaper reports in the few days following the wreck provided names of survivors and victims as best they could, as the story came into focus. Some of the passengers whose bodies were swept out to sea obviously took longer to acknowledge as being onboard. One of the victims whose body was never recovered was consistently referred to only as “Mr. Sargent” (sometimes Sargeant). Historian William Goold’s account of the tragedy eighty years later narrowed Mr. Sargent down for us. Goold wrote that among the passengers who’d perished was “a son of Nathan Sargent...of Portland.” Family trees on the Ancestry site provide details about Nathan Sargent, including his son Nathaniel. He was born in 1786 and apparently unmarried at the time of his death at age 21 in 1807.

22: Lydia Carver

Of all the victims of the shipwreck off Richmond Island, Lydia Carver has received the most attention over the years. She was a young woman of 24, born on June 26, 1783 to Amos and Anna (Lane) Carver of Freeport, Maine.

The wreck of the Charles is said to have cast a great gloom over the city. Historian William Goold wrote, “No fatal calamity was ever so sensibly felt by the people of the town.” Newspaper headlines included “Disastrous Shipwreck” and “Melancholy Loss.” Mr. Robbins lengthy publication, “An Elegy,” also reflected the sadness of the townspeople, as line by line, stanza by stanza, he told the story of the wreck and its victims. All of the victims’ lives had been cut short and surely all had left loved ones behind, yet Robbins dedicated a full eight stanzas to Miss Lydia Carver, far more than any of the others. He referred to her as an “intended bride,” but her story really was no more or less noteworthy than any of the others who had perished.

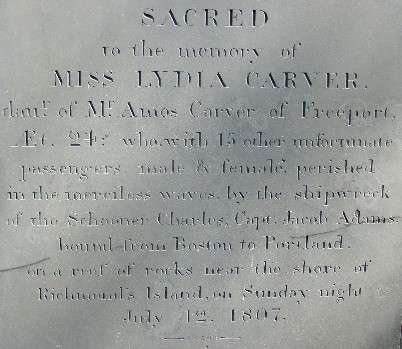

Figure 13.

- SACRED

to the memory of

MISS LYDIA CARVER,

dau’r of Mr. Amos Carver of Freeport,

AEt. 24: who, with 15 other unfortunate

passengers, male & female, perished

in the merciless waves, by the shipwreck

of the Schooner Charles, Capt. Jacob Adams,

bound from Boston to Portland,

on a reef of rocks near shore of

Richmond’s Island, on Sunday night

July 12, 1807.

So it is perhaps from Robbin’s attention to Miss Carver that—over the years—her personal story has been told and re-told, embellished and spun in such a way as to elevate her almost to a cult figure status. Lydia Carver has inspired a song,1 shipwreck-themed weddings, and designation as a “ghost bride.” One modern-day version of her story is that she was returning to Portland with her wedding party, having shopped in Boston for a wedding dress. Having drowned in the wreck, her body washed ashore on Cape Elizabeth and beside her lifeless body was found an open trunk holding the never-to-be-worn wedding gown. Stuck in a state of limbo, she haunts the area (especially the Inn near where she washed ashore and was buried—although the Inn notes that she is a “friendly spirit” so as to not scare away potential customers).

None of the newspaper accounts of the tragedy include any indication that she was with her wedding party; in fact, the only other woman aboard who we are not able to connect with other family members on the same trip is Mrs./Miss White. No accounts of the recovery of victims included details of a trunk or a wedding dress.

The truth is that Lydia Carver was one of 16 victims of this accident. Her body did wash ashore at Cape Elizabeth and she was buried at the seaside cemetery near where she was found. Her slate marker, very similar in size and design to the one carved for Mary Stonehouse, is yet another gravestone that was created by Alpheus Cary for the people lost in the wreck of the Charles.

Figure 14.

Detail of Lydia Carver’s marker

Summary

Robbins’ “An Elegy” was not the only contemporary poetic tribute to this event. Thomas Shaw of Standish, Maine, composed a tribute that was printed on July 14, 1807, as a Broadside entitled, “Melancholy Shipwreck.” Shaw’s tribute consists of 116 lines in 29 stanzas. Most interesting about his publication is the illustration at the top, which shows 16 caskets for the 12 adults and four children lost (Figure 0). Cargo on the ship was valued at $25,000, only about $3,000 of which was able to be recovered. And of the 22 people aboard the Charles, six were saved and sixteen were lost. Nine bodies were recovered, but seven were never found and so are considered to be buried at sea. Except for Miss Carver, I believe the other eight bodies found were all buried at Eastern Cemetery (though only half of those are confirmed by the presence of a marker). In 1886, Goold wrote of Mrs. Stonehouse, Mrs. Hayden and Robert Hayden, “Their gravestones with pathetic inscriptions, and the stones in memory of the Captain and his wife are near the east corner of the eastern burial ground.” The fact that he mentioned no other grave markers may mean that the four others were put in unmarked graves. Yet vandalism at Eastern Cemetery, especially in the eastern corner, has been heavy over the years. Perhaps grave markers were placed for the other four, but the stones were stolen, broken, or otherwise lost between 1807 and 1886. It would be wonderful if someday during conservation activity we recovered a long-lost marker for Mr. Jenks, Mr. Tandy, Mrs./Miss White, or the Richards child.

| Survivors Rescued (6) | Deceased (16) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From Island | From Shipwreck | Body recovered | Never recovered | |

| Mr. Cook | x | |||

| Mr. Moonie (Monie) | x | |||

| Sidney Thaxter | x | |||

| Mr. Pote | x | |||

| Samuel Richards | x | |||

| Mr. Williams (crew member) | x | |||

| Capt. Jacob Adams (crew member) | x | |||

| Lydia Carver | x | |||

| Eliza Hayden | x | |||

| Robert Hayden | x | |||

| Eleazer Alley Jenks | x | |||

| Richards family child #1 | x | |||

| Mary Stonehouse | x | |||

| (Thomas) Tandy (crew member) | x | |||

| Mrs./Miss White | x | |||

| Dorcas Adams | x | |||

| Thomas Phillips (crew member) | x | |||

| Mrs. Richards | x | |||

| Richards family child #2 | x | |||

| Miss Richards (of Dedham, Mass.) | x | |||

| Eben Ruby (crew member) | x | |||

| Nathaniel Sargent | x | |||

| *Most likely buried at Eastern Cemetery near the four others known to be there. | ||||

| Capt. Jacob Adams (crew member) | x | |||

| Lydia Carver | x | |||

| Eliza Hayden | x | |||

| Robert Hayden | x | |||

| Eleazer Alley Jenks | x | |||

| Richards family child #1 | x | |||

| Mary Stonehouse | x | |||

| (Thomas) Tandy (crew member) | x | |||

| Mrs./Miss White | x | |||

| Dorcas Adams | x | |||

| Thomas Phillips (crew member) | x | |||

| Mrs. Richards | x | |||

| Richards family child #2 | x | |||

| Miss Richards (of Dedham, Mass.) | x | |||

| Eben Ruby (crew member) | x | |||

| Nathaniel Sargent | x | |||

Sources

Description and PDF version: The Wreck of the Schooner Charles

- Adams, Andrew N., A Genealogical History of Robert Adams... The Tuttle Co. Printers, Rutland, VT: 1900.

- Colesworthy, Daniel Clement, Chronicles of Casco Bay. Sanborn and Carter, Portland, Maine: 1850.

- Daggett, Windsor, A Down-East Yankee From the District of Maine. A.J Huston, Portland, Maine: 1920.

- Goold, William, Portland in the Past... B. Thurston & Company, Portland, Maine: 1886.

- Greenleaf, James Edward, Genealogy of the Greenleaf Family, Frank Wood Printing, Boston: 1896.

- Little, George Thomas, Genealogical and Family History of the State of Maine. Lewis Historical Publishing Company, New York: 1909.

- Noyes, R. Webb, A Bibliography of Maine Imprints to 1820. Printed by Mrs. and Mr. R. Webb Noyes, Stonington, Maine: 1930.

- Parsons, Henry S., A Check List of American Eighteenth Century Newspapers in the Library of Congress (revised edition). US Printing Office, Washington, DC: 1936.

- Robbins, Ebenezer, An Elegy on the Distressing Scene of the Schooner Charles. 1807.

- Romano, Ron, Early Gravestones in Southern Maine... History Press, Mt. Pleasant, SC: 2016.

- Shaw, Ralph R. & Shoemaker, Richard H., American Bibliography. The Scarecrow Press, Inc., New York: 1958, 1961.

- Shaw, Thomas, Melancholy Shipwreck. Portland, Maine: July 14, 1807.

- Sheppard, John H., The Life of Samuel Tucker, Alfred Mudge & Son, Boston, MA: 1868.

- Walworth, Reuben H., Hyde Genealogy. J. Munsell, Albany, NY: 1864.

- Zwicker, Roxie, Haunted Portland. Arcadia Publishing, Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina: 2007.

Newspapers

- Eastern Argus, Weekly Eastern Argus (Portland)

- Newburyport (MA) Gazette

- New York Evening Post

- New York Spectator

- Portland Gazette and Maine Advertiser

- Portland Press Herald

- Repertory (Boston)

Websites and Miscellaneous

- Ancestry

- Find a Grave

- Grave Addiction

- Strange Maine

- Massachusetts State Archives, Boston, MA

- Portland Freedom Trail walking tour map/brochure

- Vital Records of Portland, Maine

References

1 The band, Icarus Witch, produced an album in 2005 entitled “Capture the Magic,” which includes a song “The Ghost of Xavier Holmes.” While no Xavier Holmes was on board the ship, the song’s lyrics reflect the wreck of the Charles, and the acknowledgements on the album include “Lydia Carver (RIP) ... at Portland Maine.” back to text 1