The Asa Clapp Monuments

Fifth in a series of Occasional Papers about Eastern Cemetery in Portland, Maine

by Ron Romano

© 2018

A volunteer working at Maine Historical Society in 2017 discovered a receipt in the Asa Clapp papers held in the Maine Historical Society (MHS) Collections. The receipt was for a monument to decorate Clapp's family tomb at the town's Burying Ground (now Eastern Cemetery), created by Portland's first resident stone-cutter, Bartlett Adams. The receipt, in Adams' own hand, was dated 1810. Few business records from the Adams shop have survived, so the receipt is an important "new" piece. This paper provides the details of my research and findings related to the discovery of this newest piece of Bartlett Adams' history.

Contents

- Introduction

- Asa Clapp (1762–1848)

- Tomb A–83

- The Receipt

- What Does Capt. David Smith Have to Do with This?

- When Clapp Bought Tomb A–83

- Today’s Monument

- One Other Marker

- Additional Materials

- Clapp Family Notes—Four Generations

- Sources

Introduction

Portland’s sole public burying ground was already nearly 150 years old when Asa Clapp purchased a monument for a family tomb there in 1810. Unoccupied burial plots were scarce towards the end of the eighteenth century, but the cemetery had nearly doubled in size in 1795, with the acquisition of Reverend Thomas Smith’s field. The Smith acquisition provided instant relief to the town’s need for burial space, and led to a unique arrangement: the development of a series of abutting underground tombs. Over a thirty-year period (beginning about 1798), 86 underground tombs organized in four parallel rows were constructed along the border between the old and new sections of the cemetery. Each tomb is approximately twelve feet long, six feet wide and six feet tall, intended to hold up to thirty coffins. Each has a private stairway and entrance. A tomb is accessed by removing the sod and wooden planks over the stairway and then descending into the chamber.

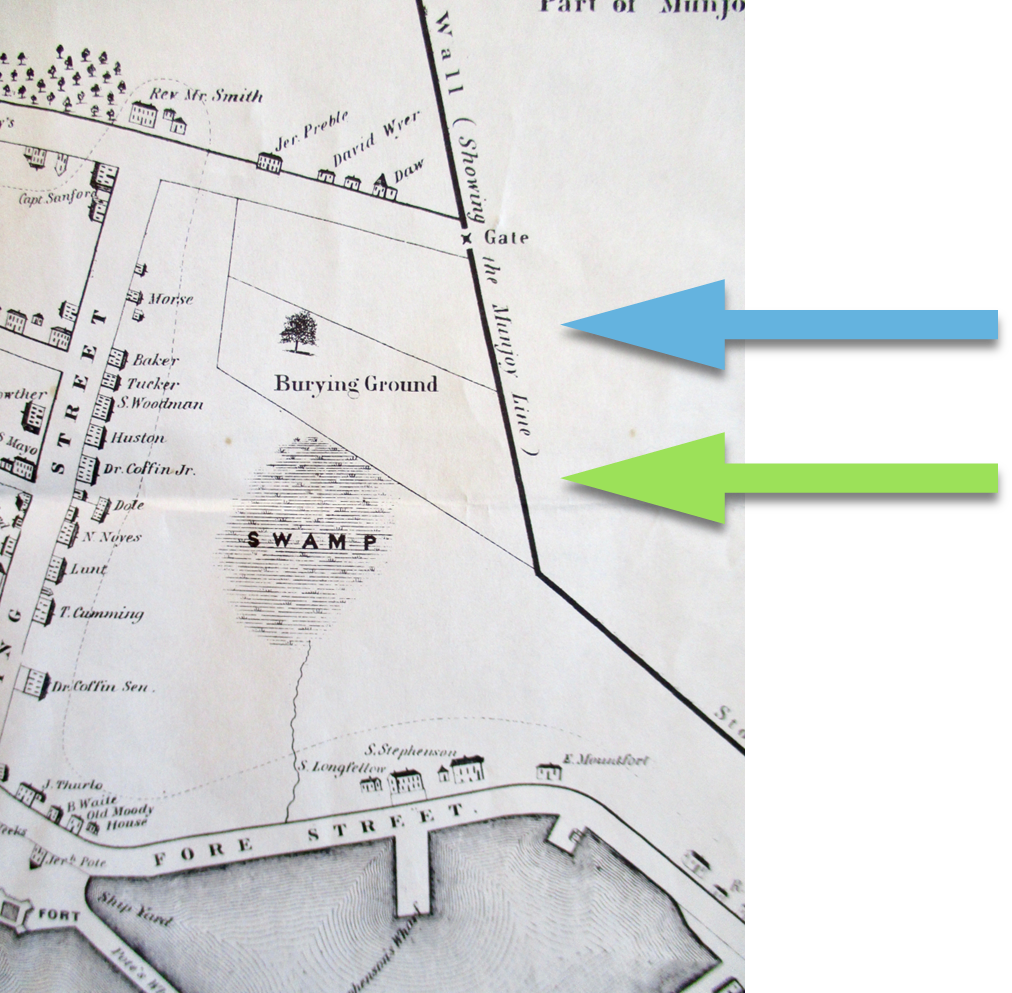

Detail of map from The History of Portland, by William Willis, showing the town in 1775 (Figure 1). The green arrow (bottom arrow) points to the original section of the Burying Ground; the blue arrow (top arrow) points to Reverend Smith's field, with its northern border on today's Congress Street and southern border abutting the Burying Ground. This land was deeded to the town in 1795, shortly before Smith died, nearly doubling the town's burial space.

Figure 1. Map

We find the town’s large and more prominent families among the list of tomb owners—Preble, Widgery, Moody, and McLellan, for example—so it’s no surprise to find Asa Clapp there as well. The tombs were likely financially out of reach for working class citizens and simply unnecessary for smaller and more transient families. Those families that did purchase tombs were able to decorate them as they wished. Today, a variety of large monuments are found, including obelisks, pedestals, table tombs (none of which still have their columns), ledgers and box tombs. The difference between the monuments found over the tombs compared to the grave markers found in the adjacent original section of the cemetery is striking and supports the fact that these tombs were purchased by the town’s wealthy.

Note on the right side of tree-lined Funeral Lane that the old section is populated by slate and marble gravestone marking individual graves, while on the left side of the lane the newer section is populated by large monuments of different varieties placed there by Portland's well-to-do (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Asa Clapp (1762–1848)

The Honorable Asa Clapp was a highly-respected citizen of Portland, whose generosity toward the community and country is well documented in many of the published biographical sketches of Maine and the histories of Portland (Sources). His accomplishments and contributions during his long life could fill pages, but a nice summary is found in the 1876 The Clapp Memorial. It reads:

He established himself as a merchant in Portland, in 1796, trading extensively and profitably, by numerous vessels, with Europe, the East and West Indies, South America, &c. He was active in the separation of Maine from Massachusetts, and was an efficient member of the Convention for forming the Constitution of Maine, in 1819, and was afterwards a Senator in the Maine legislature.

During the War of 1812, when the nation was in dire need of financial resources, Mr. Clapp voluntarily loaned the government approximately half of his substantial net worth, then signed on as a common soldier to further assist in the conflict. For a short period in the 1820s, he was the wealthiest man in Maine. He entertained three US Presidents at his home which is now a part of the Portland Museum of Art: President Monroe in 1817 and President Polk and future President Buchanan in 1847.

Tomb A–83

The Asa Clapp tomb is found in the new section of the cemetery in the first of four parallel rows of tombs just off of Funeral Lane. There are 24 tombs in that “front” row1 followed by a second row of 24, a third row of 22 and the fourth row—closest to Congress Street—of 16 tombs. Although his tomb is today numbered “83” (of 86), it was likely among the first wave of tombs built over the approximately 30-year project, given its location facing the Lane. Historical records suggest that the tombs were originally named for their owners rather than being numbered. Examples from more than three dozen such burial records are “Buried near Elder’s tomb,” “Buried by Swan’s tomb,” and “Buried in Gould tomb.” The numbering was assigned by William Goodwin during his complete (and the first known) survey of the cemetery in 1890.

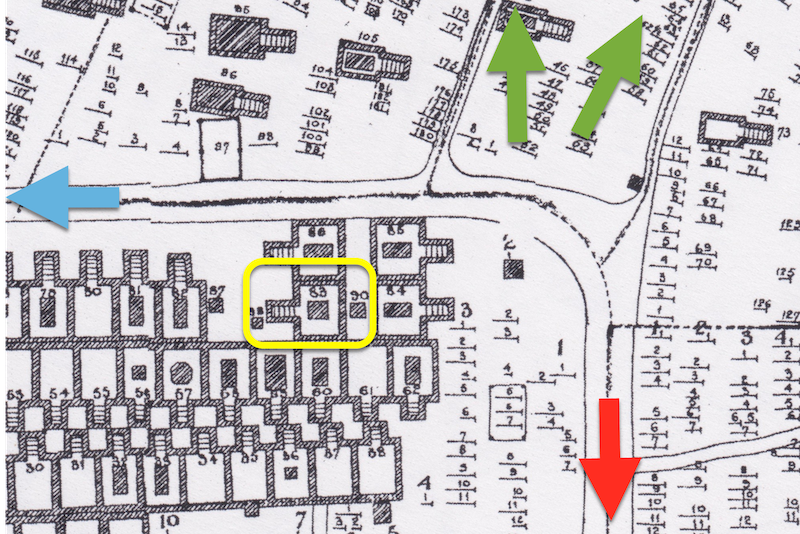

Figure 3. (Detail of Eastern Cemetery plot map courtesy of MHS)

Notes about Figure 3:

- The red arrow (lower right) is on the north/south portion of Funeral Lane and points to today's front gate on Congress Street.

- The blue arrow (left) is on the east/west portion of Funeral Lane pointing towards the Mountfort Street gate. This part of the lane separates the cemetery's old section (above) from the new section (below).

- The green arrows (top) point towards the waterfront and the original entrances to the burying ground.

- The yellow box (center) encircles the Clapp Tomb. Note its private stairway on the left. The dark square on the tomb represents the shape of the monument there, which is a square-based granite pedestal.

The Receipt

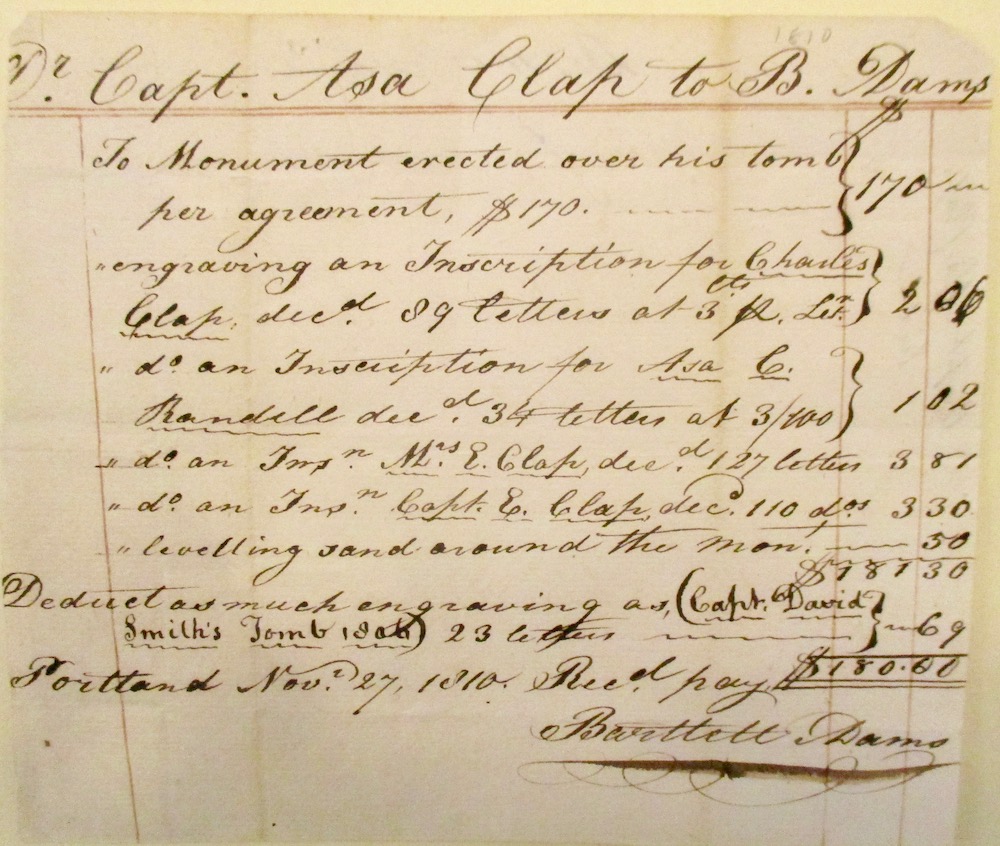

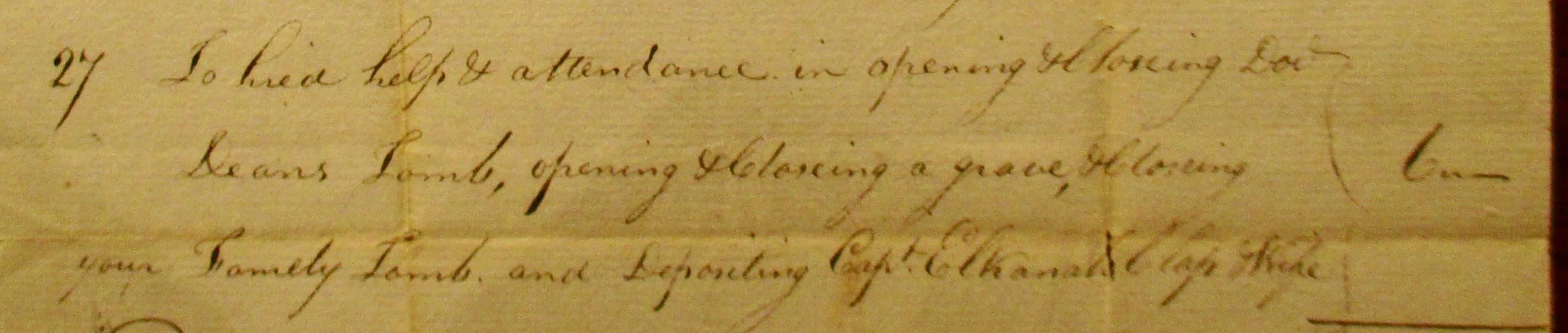

The receipt (Figure 4) found among the Clapp papers measures 6.5 by 7.5 inches. Except for one short phrase, the handwriting is that of Bartlett Adams, Portland’s first stone-cutter. It is signed and dated November 27, 1810. Adams spelled the family name as “Clap” throughout (as did Asa Clapp himself at the time).

Figure 4.

- Capt. Asa Clap to B. Adams

Monument erected over his tomb per agreement, $170

- engraving an Inscription for Charles Clap, dec’d. 89 letters at 3 cts p. ltr, $2.06

- an Inscription for Asa C. Randall dec'd. 34 letters at 3/100, $1.02

- an Ins’n Mrs. E. Clap, dec’d 127 letters, $3.81

- an Ins’n Capt. E. Clap, dec’d 110, $3.30

- levelling sand around the mon., $ .50

$181.30

Deduct as much engraving as 23 letters (Capt. David Smith’s Tomb 1806), $.69

Portland Nov. 27, 1810, Rec’d pay $180.00

Bartlett Adams

The receipt lists the “Monument erected over his tomb per agreement” at $170. There’s also a $0.50 charge for leveling sand around the monument.

The remaining four charges itemize individual inscriptions carved by Adams on the monument. Those details provide us with something new to add to the growing body of knowledge we have about Bartlett Adams’ business: that is, in 1810 he charged 3 cents per engraved letter. The four inscriptions Adams engraved, and their costs, were summarized as follows:

- Charles Clapp, 89 letters for $2.062 (He was Asa’s 5-year-old son)

- Asa C. Randall, 34 letters for $1.02 (Asa’s 8-year-old nephew)

- Elizabeth Clapp, 127 letters for $3.81 (Asa’s sister-in-law, married to his brother Elkanah)

- Elkanah Clapp, 110 letters for $3.30 (Asa’s brother)

Creating a monument involved much more than lettering, of course. Cutting the stone from its source block, shaping it, readying the surfaces for inscription, and other tasks all took days. Modern-day stone carvers Matthew Barnes and Michael Updike note that carving standard letters and numbers on marble takes about 10 minutes per character, so carving the 360 characters on the original Clapp monument would have kept Bartlett Adams busy for about 60 hours—well over a week’s work.

The sub-total on the receipt is $181.30, but should have been $180.69.3 Regardless of the minor error (or intended adjustment) in calculations, the more interesting finding here is that Bartlett then added a credit line as follows:

“Deduct as much engraving as 23 letters.” At 3 cents each, 23 letters equals $0.69, and it is that amount that Bartlett subtracted from the bill, leaving a final total owed to him by Mr. Clapp of an even $180. While the line itemizing the deduction is in Bartlett’s hand, someone else wrote in the following parenthetical 23-letter phrase: “Capt. David Smith’s Tomb 1806.”

What Does Capt. David Smith Have to Do with This?

Captain David Smith was born in 1742 and died in 1822, and would have been in his late 60s/early 70s when this transaction between Clapp and Adams took place. Smith’s name appears in one of Asa Clapp’s business journals, with some financial transactions recorded between 1804 and 1807, so we know the men certainly knew one another. Captain Smith and many members of his family were laid to rest in Tomb F–105, just a few steps across Funeral Lane from the Clapp tomb. Regardless of where he was buried, the phrase about deducting engraving on the Clapp-Adams receipt is confusing. Two ideas emerge to explain how one might “deduct engraving” though admittedly both leave more questions than answers....

- Let’s say Bartlett Adams had given Asa Clapp an estimate for monument work involving 100 letters and a total charge of $3.00 (3 cents per letter). Then Clapp decided he wanted a shorter inscription. It would make sense for Bartlett to update the estimate with “deduct engraving of 23 letters” and issue the credit of $0.69. Sounds possible, except the credit on Clapp’s bill apparently relates to Captain Smith.

- Perhaps Captain Smith owned that tomb before Clapp and had a small “owner’s monument” placed on it that read “Capt. David Smith’s Tomb 1806.” When he sold the tomb to Clapp, Clapp asked Bartlett to chisel off Smith’s name and date. This also sounds possible, but wouldn’t Bartlett charge for his efforts to remove the Smith name from a stone?

For now, this is simply a curiosity.

When Clapp Bought Tomb A–83

Less mysterious are the circumstances surrounding Clapp’s purchase of the tomb. His brother and sister-in-law died within 3 weeks of each other in the fall of 1810. Elizabeth Clapp died on September 20 at the age of 38. Sixteen days later on October 5 her husband Elkanah Clapp—Asa’s younger brother—died at the age of 44.

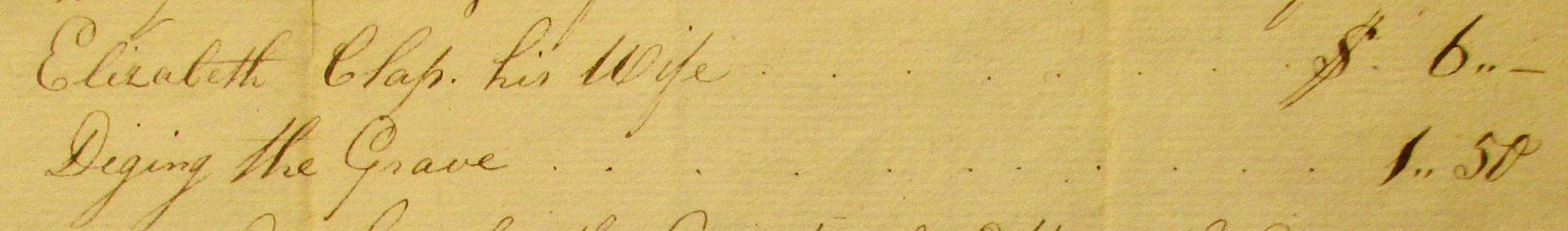

In the Clapp papers at MHS, there is a bill for their final expenses on an estate document in Elkanah’s name. It’s interesting to note (Figure 5) that on September 25th, the itemization for Elizabeth reads “digging the grave,” a service that cost the estate $1.50. So, it appears that Elizabeth was not entombed, but buried in the open ground.

Figure 5.

- Elizabeth Clap, his wife $6

Digging the Grave $.50

Further down the same document, for Elkanah, we find on October 8 a $1.25 charge for “opening and closing the tomb,” but the tomb referenced here seems to be one owned by Dr. Samuel Deane, immediately abutting Tomb A–83. The fact that Elizabeth and Elkanah, who had died less than three weeks apart, were put in two different (and temporary) places suggests that Asa Clapp did not yet own Tomb A–83.

Then, on October 27, this: “...hired help & attendance in opening and closing Doc’t Deane’s Tomb, opening & closing a grave, & closing your Family Tomb and depositing Capt. Elkanah Clap there” (Figure 6). Asa Clapp handled his brother’s estate, so the reference to “your tomb” on October 27 suggests that Asa Clapp completed purchase of the tomb between October 8 and 27.

Figure 6.

- Hired help & attendance in opening and closing Doc’t Deane’s Tomb, opening & closing a grave, & closing your Family Tomb and depositing Capt. Elkanah Clap there.

Here’s a likely timeline for the fall of 1810:

- September 20: Elizabeth Clapp dies, and is buried in a fresh grave at Eastern Cemetery

- October 8: Elkanah dies, and being so soon after Elizabeth’s passing, Asa Clapp decides to purchase a tomb for the family. In the meantime, he asks Dr. Deane if Deane will allow the temporary holding of Elkanah’s remains in Deane’s tomb as opposed to burial in the open ground with Elizabeth

- Between October 8 and 27: Asa Clapp purchases the tomb (from Smith)

- October 27: Elkanah and Elizabeth are removed from their temporary holding places and reburied in the tomb.

- November 27: Asa Clapp engages Bartlett Adams for a monument on the tomb.

While all of this makes sense given the documents I did find in the Clapp papers, I could not find any record of a transaction to transfer ownership of Tomb A–83 from Smith to Clapp. I scoured Clapp’s ledgers, cash books, and journals for 1810, yet found nothing about the tomb. Checking online, the Cumberland County Registry of Deeds also had nothing for Clapp prior to 1817, although we know he had many real estate transactions in the early 1800s. So, more unanswered questions.

Asa’s son and nephew (named on the Adams bill) were also probably originally buried somewhere in the open ground, and were very likely disinterred and re-buried in the Clapp tomb late in 1810. Charges for their disinterment and re-burial are not included on the Elkanah estate document since they were not directly related to him.

Today's Monument

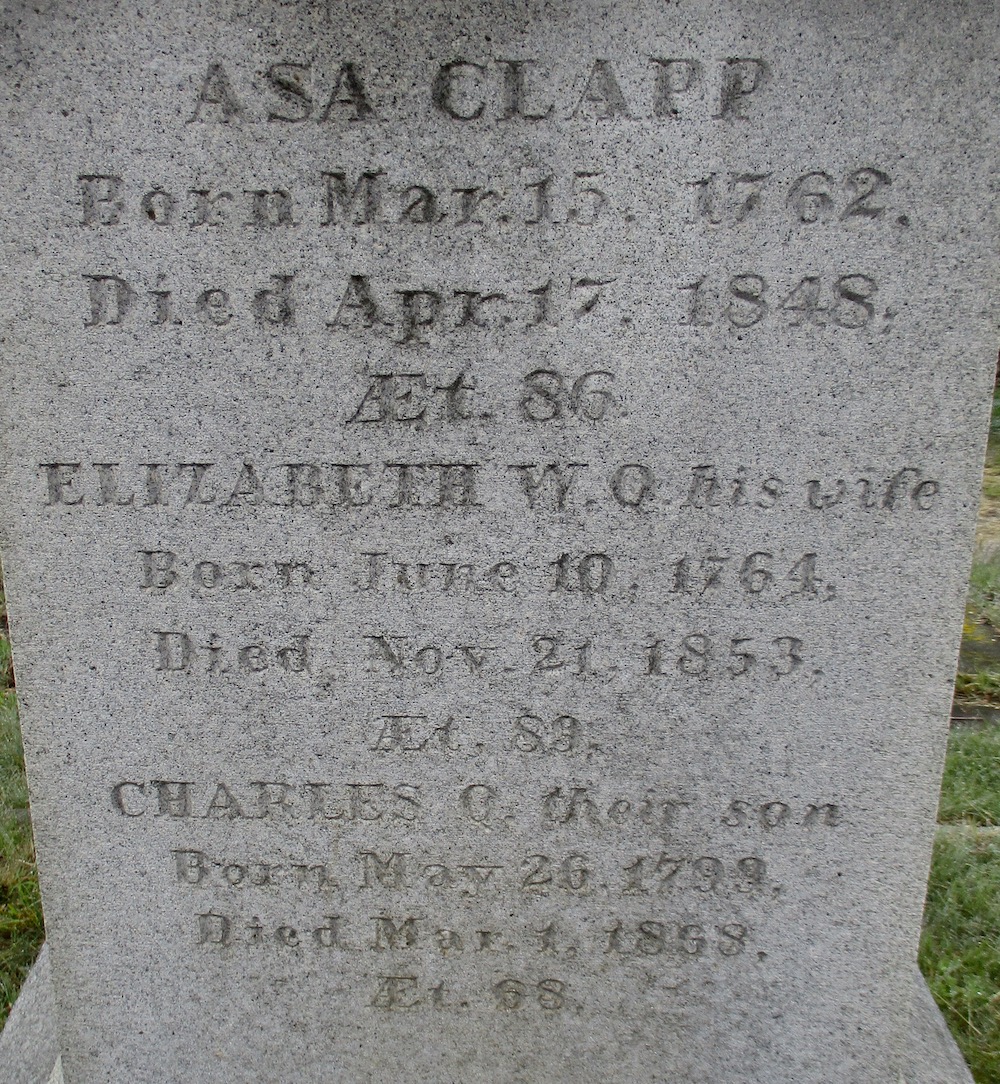

The monument that rests on the Clapp tomb today is not the one that Bartlett Adams inscribed. For large monuments, Bartlett worked primarily with marble, occasionally sandstone. The Clapp monument currently on site is granite, a much harder stone that was not in common use until the third quarter of the 19th century, when machine tools allowed for inscribing letters. My belief is that the monument (probably marble) Adams erected for Clapp in 1810 weathered and eroded over the ensuing decades, and that sometime after Asa Clapp’s death in 1848 the Clapp family replaced the monument with the granite one found today (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Another clue to the fact that the current monument is not the one Adams produced is that the number of characters inscribed for each of the four individuals named on the 1810 receipt do not match what we find today.

- Charles Clapp should have 89 letters, but has only 29 on the current monument.

- Asa Randall should have 34 letters, but has only 27.

- Elizabeth Clapp should have 127 letters, but we find only 45 today.

- Elkanah Clapp should have had 110 letters, but we find only 28.

It makes sense that in 1810, with Elkanah and Elizabeth being the only adults in the tomb, they would have had more lengthy inscriptions. But after Asa himself died in 1848 and the new monument erected, their inscriptions were reduced to just their names and dates.

There are four panels on the new monument, each with some inscription, and there are 12 names listed on the monument (Figures 8 to 11). We find no biographical details other than dates and ages, plus the occasional familial relationship noted (“his wife” for example).

Figure 8. North facing panel. Asa Clapp, Elizabeth W.Q. Clapp, Charles Q. Clapp

- ASA CLAPP

Born Mar. 15, 1762

Died Apr. 17, 1848,

AEt. 86

ELIZABETH W. Q. his wife

Born June 10, 1764

Died Nov. 21, 1853,

AEt. 89

CHARLES Q., their son

Born May 26, 1799

Died Mar. 1, 1868

AEt. 68

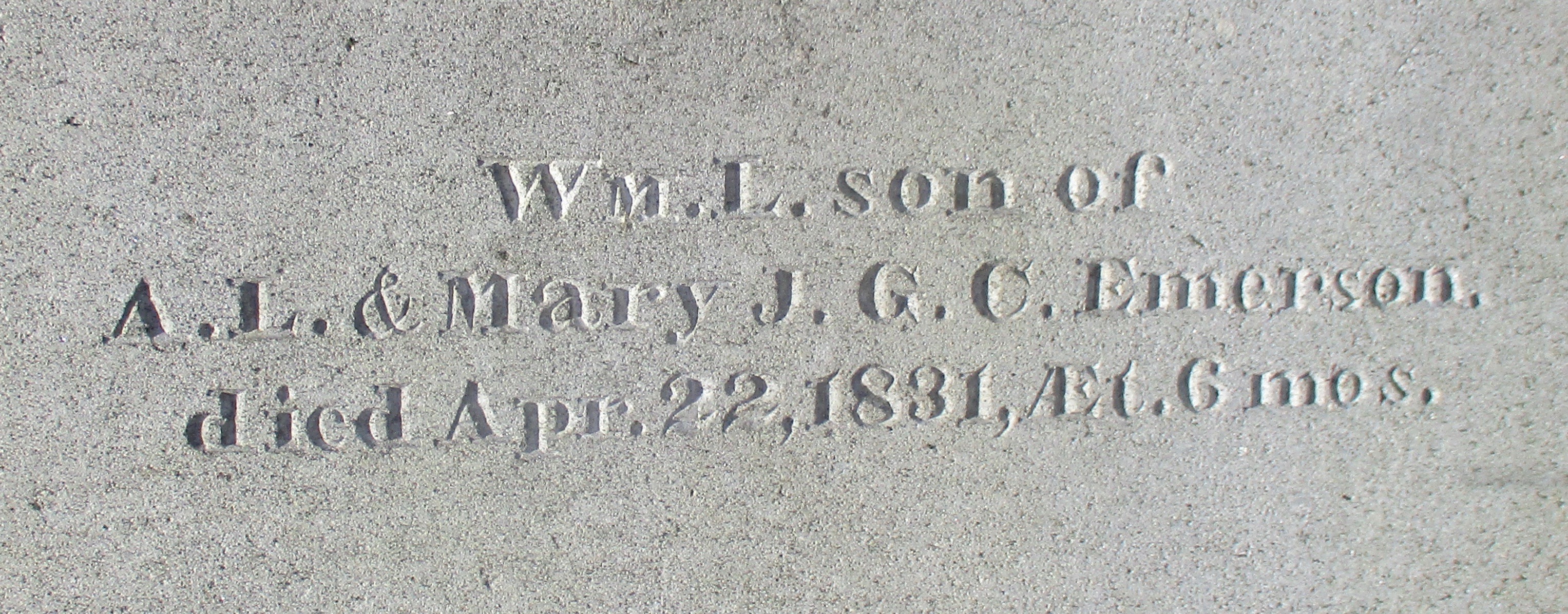

Figure 9. West facing panel. William L. Emerson

- WM. L. son of

A. L. & Mary J. G. C. Emerson,

died Apr. 22, 1831, AEt. 6 mos.

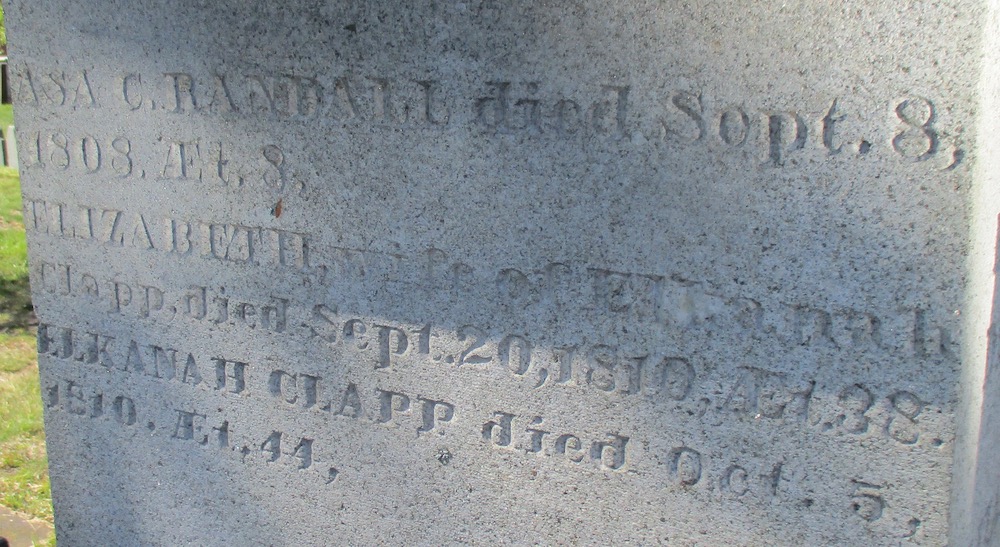

Figure 10. East facing panel. Asa C. Randall, Elizabeth Randall, Elkanah Clapp

- ASA C. RANDALL, died Sept. 3, 1808, AEt. 8

ELIZABETH, wife of ELKANAH Clapp, died Sept. 20, 1810, AEt. 38.

ELKANAH CLAPP died Oct. 5, 1810, AEt. 44

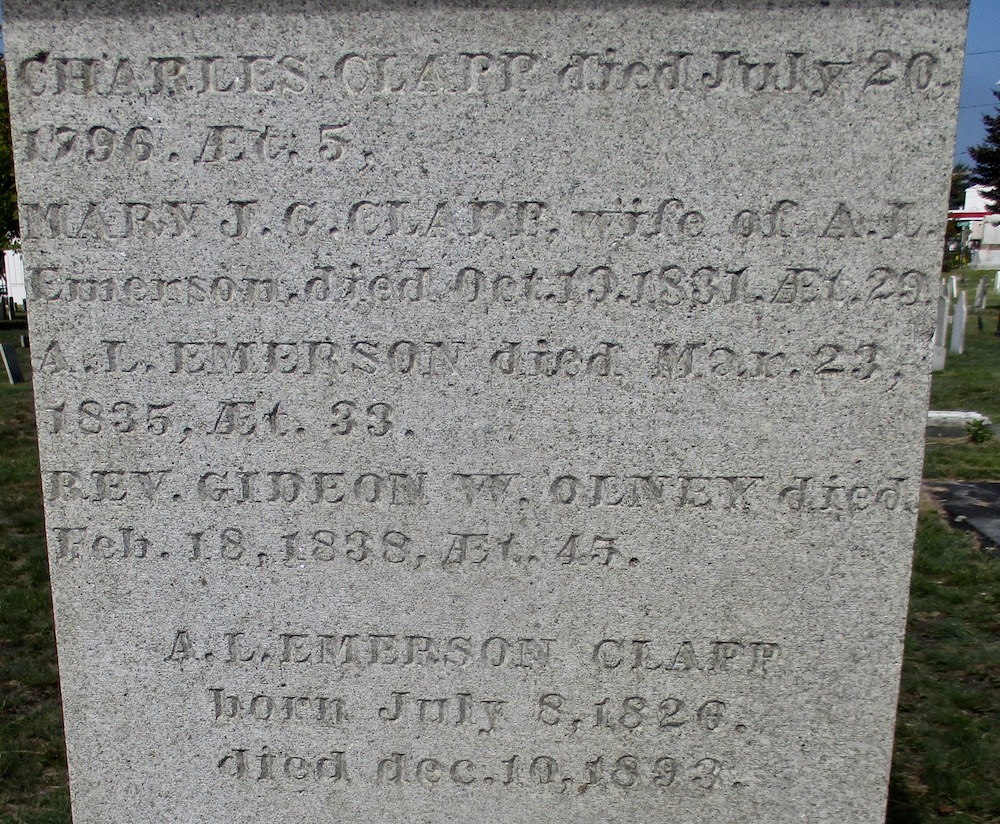

Figure 11. South facing panel. Charles Clapp, Mary J.G.C. Emerson, Andrew L. Emerson, Rev. Gideon W. Olney, Andrew L.E. Clapp

- CHARLES CLAPP, died July 20, 1796, AEt. 5

MARY J. G. CLAPP, wife of A. L. Emerson, died Oct. 19, 1831, AEt. 29

A. L. EMERSON, died Mar. 23, 1835, AEt. 33

REV. GIDEON W. OLNEY, died Feb. 18, 1838, AEt. 45

A. L. EMERSON CLAPP born July 8, 1826, died dec. 10, 1893.

Asa Clapp’s papers in the collection at MHS end by the time of his death in 1848, so we don’t know when the new monument was placed on the tomb. What’s clear is that the inscriptions were not all done at the same time. Note two panels have center-justified text, one has left-justified text and one has a mix of the two. Also some names have “born” and “died” dates, while others have just “died.”

One Other Marker

Those visiting the Clapp family tomb today will find one additional marker, that for the War of 1812 veteran, Kinicum Randall (Figure 12). Mr. Randall is most likely related to Phineas Randall, Asa Clapp’s brother-in-law who married his sister Susan, though I was not able to find vital records to confirm the familial relationship. Kinicum died in 1842, but was not buried in the tomb, as his death record places him at Eastern Cemetery with the note “grave stone lost.” Other members of Asa Clapp’s family were buried in the tomb after 1842 (including Asa himself) and are memorialized on the family monument. Kinicum’s name is not inscribed on the monument, so whoever placed this modern veteran’s marker may just have made some assumptions about a family link.

Figure 12.

- KINICUM RANDALL

CORP MASS MILITIA

WAR OF 1812

1785–1842

Additional Materials

Here are two additional informational sources.

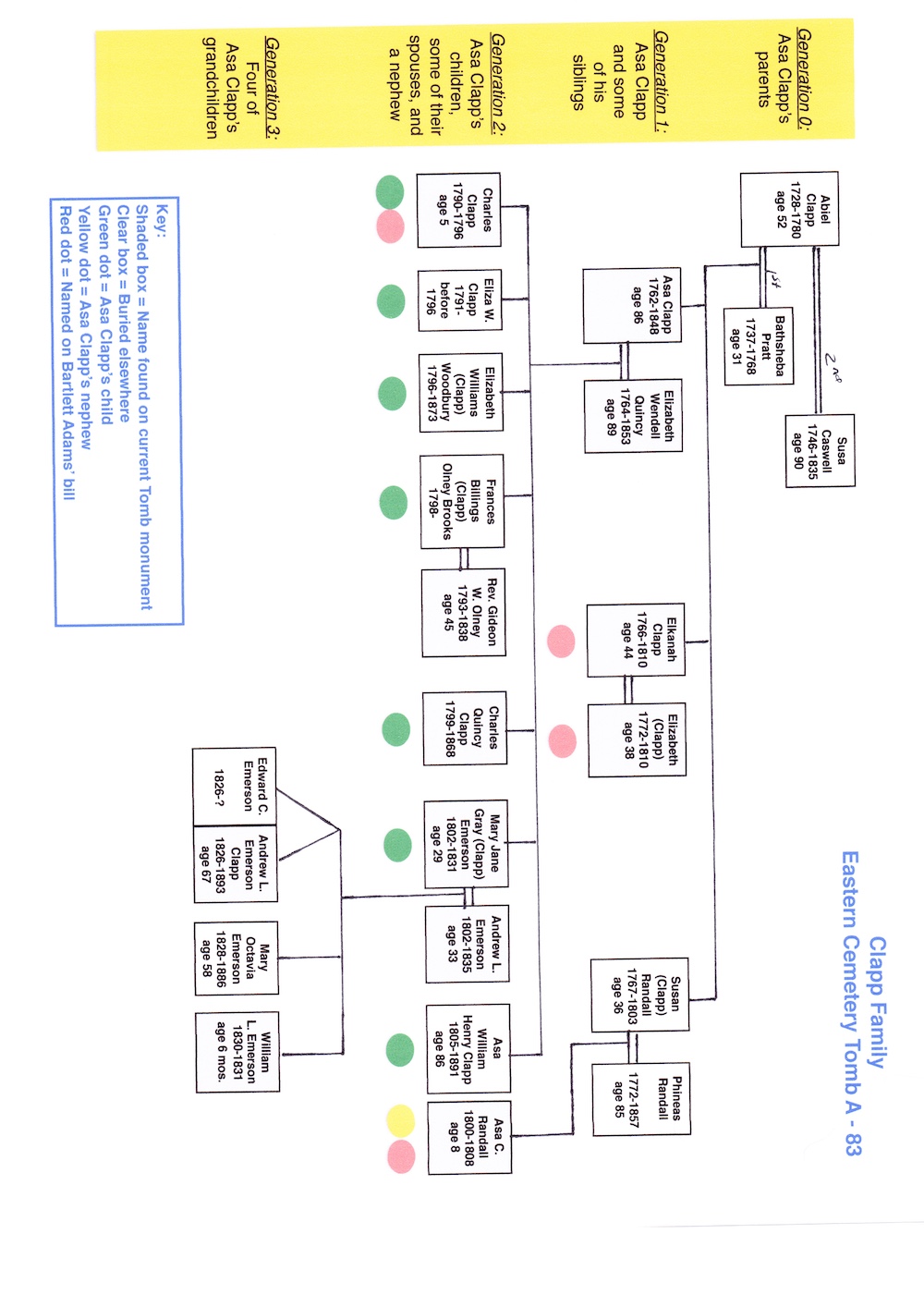

This first one (Figure 13), entitled “Clapp Family Eastern Cemetery Tomb A–83,” consists of a four-generation family tree of some of Asa Clapp’s family. The shaded boxes on the tree show the 12 who are named on the current monument. Those with a red dot are the four who were named on the original bill from 1810. Asa Clapp’s children and nephew entombed with him are marked with green and yellow dots as noted.

Figure 13.

Clapp Family Notes—Four Generations

This second one provides a few additional biographical details about the people entombed with Asa Clapp.

| Name | Notes | Asa was... |

|---|---|---|

| Abiel Clapp |

|

18 when his father died |

| Bathsheba Pratt |

|

6 when his mother died |

| Susa Caswell (sometimes Suse) |

|

10 when his step-mother married his father |

| Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| *One of the 12 members listed on the Clapp monument found today at Eastern Cemetery. | |||

| Asa Clapp |

|

86 when he died | Yes |

| Elizabeth Wendell Quincy Clapp |

|

25 when he married Elizabeth | Yes |

| Elkanah Clapp |

|

4 when his brother Elkanah was born | Yes |

| Elizabeth (Clapp) Clapp |

|

- | Yes |

| Susan Clapp Randall |

|

5 when his sister Susan was born | No |

| Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| *One of the 12 members listed on the Clapp monument found today at Eastern Cemetery. | |||

| Charles Clapp |

|

28 when his first child was born | Yes |

| Eliza W. Clapp |

|

- | |

| Elizabeth Williams Clapp Woodbury |

[For space limitations, Levi Woodbury does not appear on the family tree diagram] |

57 when his daughter married Levi Woodbury | |

| Frances Billings Clapp Olney |

|

- | No |

| Rev. Gideon W. Olney |

|

- | Yes |

| Charles Quincy Clapp |

[For space limitations, Julia does not appear on the family tree diagram] |

70 when his son Charles built the Spring Street mansion | Yes |

| Mary Jane Gray Clapp Emerson |

|

- | Yes |

| Andrew Leonard Emerson |

|

80 when his son became Mayor of Portland | Yes |

| Asa William Henry Clapp |

[For space limitations, Julia does not appear on the family tree diagram] |

- | No |

| Asa C. Randall |

|

- | Yes |

| Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| *One of the 12 members listed on the Clapp monument found today at Eastern Cemetery. | |||

| Edward C. Emerson and Andrew L. Emerson Clapp |

|

64 when his twin grandsons were born | Yes |

| Mary Octavia Emerson |

|

- | No |

| William L. Emerson |

|

- | Yes |

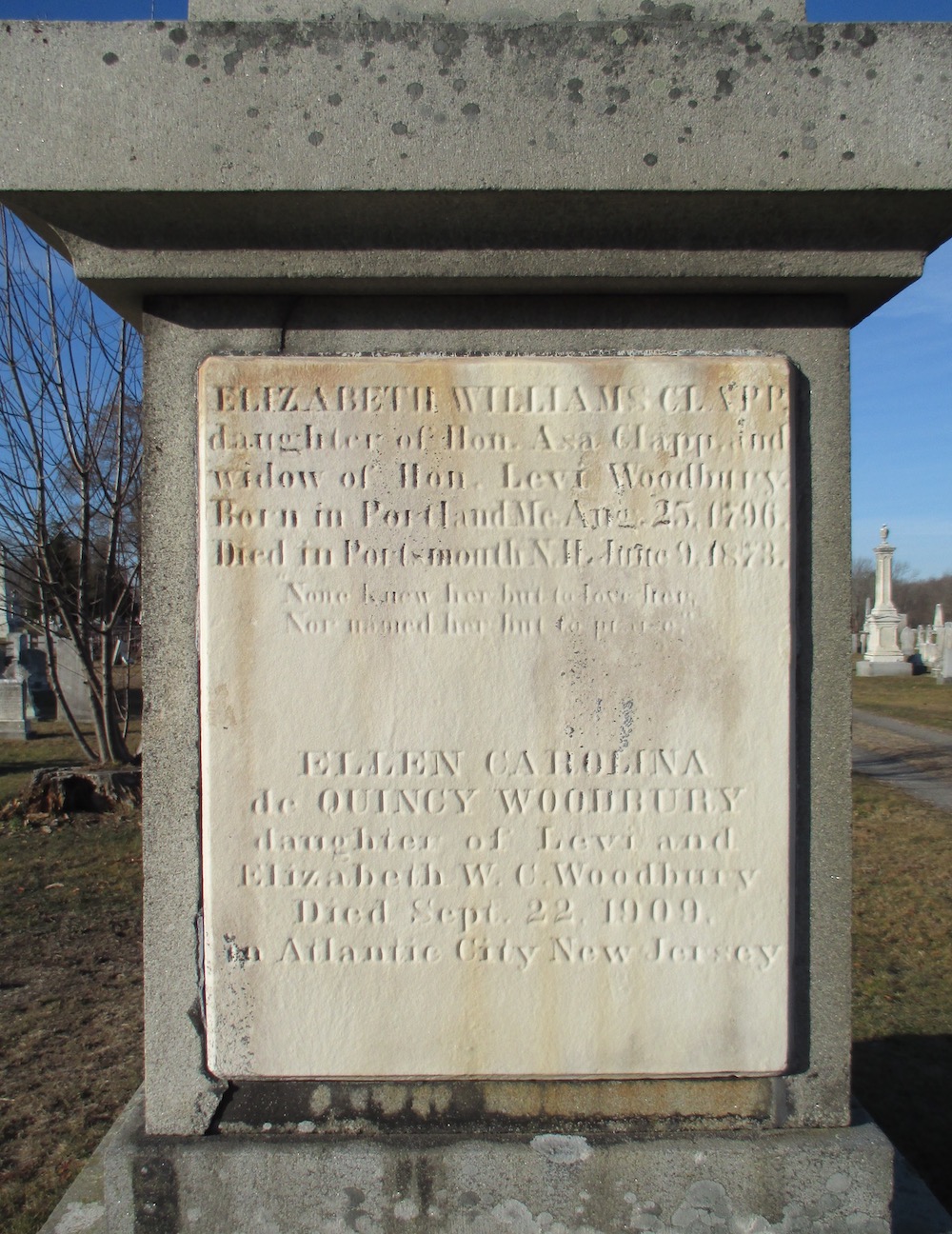

The impressive monument for Asa Clapp's daughter Elizabeth and her family, found at Harmony Grove Cemetery in Portsmouth, NH (Figures 14 and 15).

Figure 14.

Figure 15.

- Elizabeth Williams Clapp

daughter of Hon. Asa Clapp and

widow of Hon. Levi Woobury

Born in Portland, Me. Aug 25, 1796,

Died in Portsmouth, N.H. June 9, 1873.

None knew her to lose her,

Nor named her but to praise.

Ellen Carolina

de Quincy Woodbury

daughter of Levi and

Elizabeth W.C. Woodbury

Died Sept. 22, 1909

in Atlantic City New Jersey

Sources

Description and PDF version: The Asa Clapp Monuments

- Ancestry.com (Vital records, Census records, Immigration files, etc.)

- Find-a-Grave.com

- Collections of Maine Historical Society

- Clayton, W. Woodford. History of Cumberland Co., Maine. Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1880.

- Clapp, Ebenezer (compiler), The Clapp Memorial. Boston: David Clapp & Son Publishers, 1876.

- Davis, William T., The New England States, Volume 3. Boston: D. H. Hurd & Co, 1897.

- DeBolt, Mary M., Lineage Book: National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Vol. LXXI. Washington, DC: 1908.

- Goold, WIlliam. Portland in the Past. B. Thurston & Co Publishers, 1886.

- Jordan, William B. Jr., Burial Records, 1717 - 1962 of the Eastern Cemetery, Portland, Maine. Heritage Books, 2009.

- Jordan, William B. Jr., Record of Interments with Historical Notes, 1978. Collections of the Maine Historical Society.

- Maine - A History. Centennial Edition. New York: The American Historical Society, 1919.

- Olney, James H., A Genealogy of the Descendants of Thomas Olney. Providence RI, 1889.

- Portland City Guide. Portland, ME: Forest City Printing Company, 1940.

- Stover, Arthur Douglas, Eminent Mainers. Gardiner Maine: Tilbury House Publishers, 2006.

- Willis, William. The History of Portland (facsimile edition). New Hampshire Publishing Company, 1972.

References

1 “Front” is used here since the main entrance to the cemetery was - until the 1860s - on the waterfront side of the land, where Federal Street runs today. back to text 1

2 There is a manual correction here for unknown reasons. 89 letters at 3 cents should be $2.67. A close look at this line of the receipt shows that “$2.67” was there, but overwritten with the figure $2.06. back to text 2

3 This subtotal of $181.30 would be correct if he used the original $2.67 for Charles’ inscription of 89 letters. It appears he revised Charles’ charges down to $2.06, but not the sub-total. Had he also revised the sub-total, it would have been $180.69. back to text 3