Henry Hanson: A Marble Worker Leaves His Mark

Sixth in a series of Occasional Papers about Eastern Cemetery in Portland, Maine

by Ron Romano

© 2018

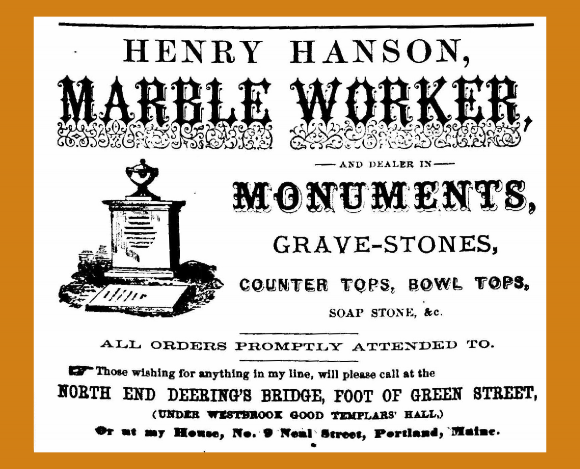

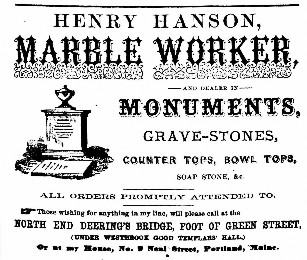

Figure 0

- Henry Hanson, Marble Worker, and Dealer in

Monuments, Grave-Stones, Counter Tops, Bowl Tops, Soap Stone &c.

All orders promptly attended to.

Those wishing for anything in my line, will please call at the North End Deering’s Bridge, foot of Green Street, (Under Westbrook Good Templars’ Hall) or at my house, No. 9 Neal Street, Portland, Maine.

Volunteers working with Spirits Alive—the friends of Portland’s Eastern Cemetery—have cleaned, straightened or repaired nearly 400 grave markers between 2013 and 2018. The conservation crew has begun to take on more challenging gravestones, such as those broken in multiple pieces or ones recovered from under the sod. In 2018, three marble markers were recovered that held carver signatures. A signature on a fourth marker was also found during a random walk. In all, ten gravestones are now known to be signed, and six of those are from one shop—that of marble worker Henry Hanson. This paper looks at the life and work of this nineteenth century stonecutter.

Contents

- Introduction

- Portland’s Stonecutters of the 1830s & 1840s

- The 1850s

- Marker Signatures at Eastern Cemetery

- One Signed Slate

- Henry Hanson (1820–1905)

- The 1860s Marble Markers

- The 1870s Markers

- The Sixth Signature—A Fragment

- The Leafy Flourish

- Through the Turn of the Century

- Family Notes

- Eastern Cemetery Plot Locations of Signed Markers

- Continuing Work

- Sources

Introduction

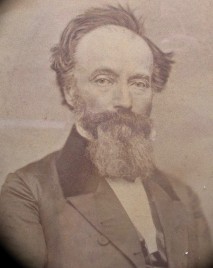

Figure 1. Joseph R. Thompson (photo courtesy Maine Charitable Mechanic Association)

The vast majority of gravestones found at historic Eastern Cemetery were not signed by their makers. It just wasn’t common practice for stonecutters to do so during the cemetery’s first 200 years, the mid-1600s to the mid-1800s. But things began to change by about 1850 as more stonecutters arrived in Portland to meet the demands of the city’s growing population.

In 1854, Evergreen Cemetery was established. Modeled after Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Evergreen was the area’s first "rural cemetery" that was designed to encourage visitation. Featuring ponds, winding paths, mausoleums, and a great variety of trees and shrubs on its more than 200 acres, Evergreen was as much a public park as a cemetery. Residents visited not just to mourn, but to picnic, visit with friends, stroll, and appreciate nature.

Unlike the more traditional utilitarian graveyards with plots organized in rows, burial space at Evergreen was arranged in varying lot sizes and shapes. Many families erected elaborate monuments, even sculptures, on their lots. It’s no surprise that the number of stonecutters producing grave stones increased in this period.

Portland’s Stonecutters of the 1830s & 1840s

For a generation following the 1828 death of Portland’s first resident stone cutter, Bartlett Adams, only one stone shop flourished—that of Joseph R. Thompson. He was a successor of Adams, and for a few years co-owned the business with partner Francis Ilsley, who had worked in Bartlett Adams’ shop at the time of Adams’ death. Ilsley left the partnership by 1834 to pursue a career as a vocal instructor and professional singer, but Thompson remained a very successful stonecutter for about four decades.

Thompson was President of the Maine Charitable Mechanic Association in 1845 & 1846. He and his wife raised 13 children; three of his sons—Henry, Enoch, and Sumner—eventually became marble workers in their father’s shop. Enoch succeeded his father and had a shop on the corner of Cumberland Avenue and Preble Street for many years.

A review of Portland’s directories published in the 1830s and 1840s confirms that Thompson owned the only stone shop in town. He is the single stonecutter to have both business and home addresses provided. The few other men identified as stonecutters have just one address. In the 1837 directory, we find stonecutters Josiah Smith and Joseph Currier located "at J. R. Thompson’s." They likely boarded with Thompson as apprentices or journeymen. Stonecutters Stephen Estes and Alexander Briggs lived "at Joseph Bonney’s" and while one might jump to the conclusion that Bonney owned a stone shop and, like Thompson, was housing his workers there, a closer look reveals that Bonney actually ran a boarding house. Norman Mead lived "at Isaac Davis’," but Davis was a Methodist sexton, not a stone man.

Another indication that Thompson was the only such business in town was his lack of advertisements. The first directory to prominently feature business advertisements was printed in 1846. Among the pages upon pages of ads, we find no stone shops represented. Perhaps Thompson thought, "with no competitors, why spend money on ads?"

But ... competition came soon enough, as Portland’s growth brought greater opportunities for stonecutters to offer their wares. By the early part of the next decade, Thompson was joined by many others, some of whom opened new shops and others who just worked in them.

The 1850s

The directories of the 1850s list at least 50 men working in Portland in the stonecutting trade. Some appear with the occupation of "marble worker," while others have the more traditional designation of "stone cutter."1 The 1852 directory has William Evans, marble worker, and Pierce Goss, stonecutter, "with JR Thompson" (on Federal Street), but living at 121 Exchange Street.

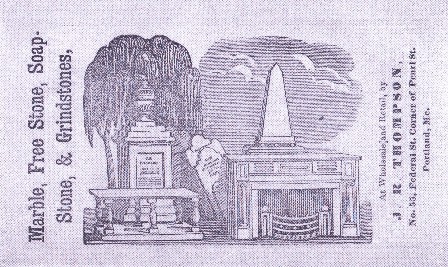

The directory for 1850/51 is the first to feature advertisements for stone shops, marking the beginning of the more competitive period. Thompson placed an impressive full-page ad (Figure 2 shows it as published, Figure 3 shows it turned 90 degrees), complete with examples of his products. Two other smaller ads also appeared confirming that new stone shops had opened in town.

Figure 2

Figure 3

- Marble, Free Stone, Soap-Stone, & Grindstones,

At Wholesale and Retail, by

J. R. THOMPSON,

No. 55, Federal St. Corner of Pearl St.

Portland, Me.

Those 1850/51 ads were for:

- Joshua T. Emery, who had a business on Lime Street, working primarily with granite

- Smith & Chaney, who operated at 308 Congress, making "Grave Stones, Monuments, Table Tombs..." (and more)

The advertisements in the 1852/53 directory brought even more shop owners into the mix:

- Life Parker was a manufacturer of monuments and grave stones, on Exchange St.

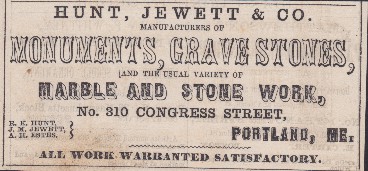

- Hunt, Jewett, & Co. offered grave stones, monuments, and tomb-tables at 308 Congress (where Smith & Chaney had advertised a couple of years earlier)

- John H. Cook had a shop immediately next door to Hunt & Jewett at 310 Congress Street, where he manufactured grave stones

Marker Signatures at Eastern Cemetery

By the 1850s stonecutters had abandoned gray slate as their primary material source for gravestones and had instead embraced imported white marble. Marble’s softness allowed carvers to create more beautiful, often three-dimensional, monuments than was possible with slate. And the stunning bright white of marble was more pleasing to visitors’ eyes than the drab gray of slate that had been used for the previous 200 years.

With so many men producing monuments, carvers also began to sign some of their work. Usually found on the lower right panel of the monument just above ground level, signatures served as a form of advertising to the multitude of cemetery visitors. One ad from Joshua Emery encouraged people to visit Evergreen Cemetery to see his work firsthand. A carver-signature survey at Evergreen would no doubt yield a fine collection of his work.

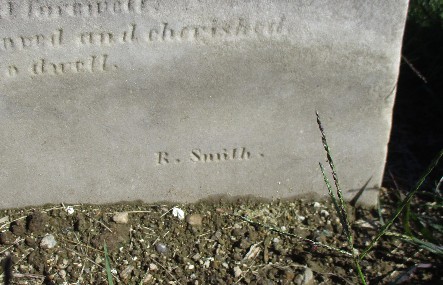

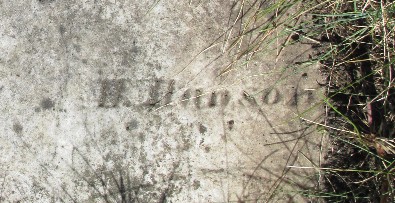

Figure 4. Marble marker for Catharine Mitchell, who died in 1846, illustrating the usual placement of a midcentury carver’s signature (found within the red circle).

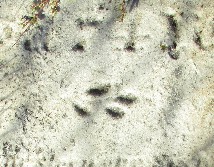

Figure 5. Detail of the marker showing signature of “R. Smith”

Some carvers included their town name with their signatures, so that visitors could more easily track them down in order to purchase markers of their own.

Although Evergreen Cemetery was the more popular place to be buried in the midcentury, some families still had available graves within their lots at Eastern Cemetery. Hundreds of burials occurred there in the 1850s and 1860s, resulting in a good collection of marble markers and great opportunity to look for carver signatures during our conservation work.

When my book, Portland’s Historic Eastern Cemetery (The History Press), was published in the fall of 2017, only six markers with signatures had been identified. That number bounced up to ten in 2018.

Four of the ten signed markers were produced at these four shops.

J. R. Thompson: Signed “Thompson,” the Mountfort family marker was recovered from the sod by Spirits Alive in 2018 and memorializes eight members of this important family.

Hunt, Jewett & Co.: A marble marker for Albert N. Murch (died 1857) was recently conserved by Spirits Alive and is signed “Hunt & Jewett.” A typical advertisement from the company is shown here (Figure 6).

Figure 6

- Hunt, Jewett & Co.

Manufacturers of Monuments, Grave Stones,

and the Usual Variety of Marble and Stone Work,

No. 310 Congress Street, Portland Me.

R.K. Hunt, J.M. Jewett, A.H. Estes

All Work Warranted Satisfactory.

R. Smith: The marble marker for Catharine Mitchell (died 1846) was recently conserved by Spirits Alive and is signed “R. Smith” (Figure 4 and Figure 5). He appears only in the 1851 directory under “R.” His full name is not known.

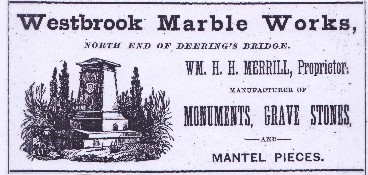

Westbrook Marble Works: A heavily eroded marble marker conserved by Spirits Alive memorializes Hannah Bradford (died 1872) and is signed “W. H. Merrill” and “Deering.”

Figure 7

- Westbrook Marble Works,

North End of Deering’s Bridge.

Wm. H.H. Merrill, Proprietor.

Manufacturer of Monuments, Grave Stones, and Mantel Pieces.

The remaining six markers bear one name: Henry Hanson. Given his hold on the majority of signatures found to date, his life and work deserve examination.

Henry Hanson (1820–1905)

Henry Hanson was born March 4, 1820, in Gilleleje, Denmark. According to his US naturalization papers, he arrived in Boston in 1843 when he was 23. Within two years, he married in Boston; his wife was 17-year-old Portland native Sarah E. Shaw.

Henry and Sarah moved to Portland in 1846 or 1847, as their first child—daughter Annie Maria—was born in Portland in December of 1847. But they did not stay long. By 1850, according to US census records, they were in Williamsburg, New York, where Henry was employed as a miller. With him were wife Sarah (age 22), daughter “Maria” (age 2) and son William Henry (just 3 days old when the census-taker visited their home).

Henry’s time in Williamsburg was equally as brief as his first stay in Portland, for in 1852, Sarah delivered their third child in Portland, a daughter they named Sarah Elizabeth. Henry stayed in Portland for the rest of his life, and he and Sarah brought four more children into the world.

One Signed Slate

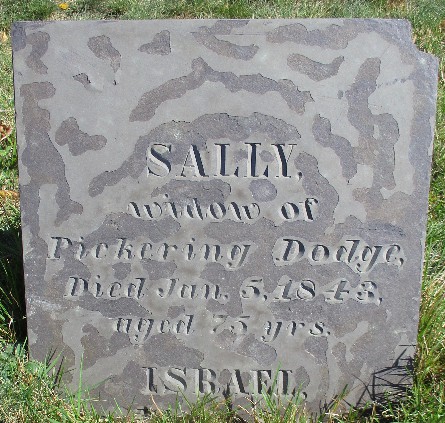

The earliest-dated grave marker at Eastern Cemetery bearing Henry’s name memorializes Sally Dodge, who died in 1843, and her son Israel, who was lost at sea at the age of 18 on the Privateer Dash.2 The marker is broken, with only the top third visible above ground level. It is slate, while the other five with Hanson’s signature are marble.

Figure 8

Figure 9

Similar markers to the Dodge stone are found throughout Maine and were likely made of stone quarried here. They are typically more reddish in color and sometimes referred to as “purple slate.” The Dodge marker is of poorer quality than most and is heavily flaking. Beyond that, it fits the typical pattern found in this collection: it has a square-cut top, lacks decoration, has deeply-cut letters, a simple inscription, and lacks an epitaph. Similar markers are dated roughly between 1840 and 1860, so the use of this material and design lasted just a generation. This marker is backdated, since Henry was in Boston at the time of Sally Dodge’s death. Henry likely made this marker during his first stay in Portland (roughly 1846 to 1848).

By the time he returned to Portland from New York in the early part of the 1850s, Henry Hanson seems to have focused on carving marble.

His first mention in town directories was in the 1852/53 edition. He is listed simply by his name, with the occupation of stonecutter and an address of 6 Congress Place. In the 1856/57 edition, Henry (then age 36) is found as a stonecutter at 38 Parris Street. Then in the 1858/59 directory, he is a stonecutter at St. John Street.

The 1860s Marble Markers

Two marble markers memorialize people who died in the 1860s and were very likely carved by Henry Hanson soon after their deaths. The 1860 census for Portland named him as “head of household.” It confirmed his birth in Denmark and gave his occupation of “marble worker.” In the household were:

- wife Sarah, age 32

- daughter Annie M., age 12

- son William H. A., age 10

- daughter Sarah E., age 8 (“Sarah Elizabeth” according to vital records)

- daughter Nelcina, age 6 (“Nelcina Ester” according to vital records)

- “nurse” Ann M. Shaw, age 38, (very likely Henry’s sister-in-law, Sarah’s older sister)

The same year the census was taken, the Hansons welcomed their fifth child, Charles Albert, born in June. Then, in 1862, sixth child Henrietta Otilla arrived in November.

Hannah M. Damrell died in 1863 at the age of 79 (so, born about 1784). If we are to believe the vital records found for her, she was 25 years younger than her husband, Captain Edward H. Damrell, who had died in 1825 at the age of 65 (so, born about 1760). I found an 1802 marriage record in Portsmouth, New Hampshire for “Captain Edward R. Damrell” and “Hanah Mendum.” Perhaps Edward R. was the son of Edward H.—certainly that would have meant the couple was the same age at the time of their marriage. In any event, the marble stone that Henry Hanson carved and signed in the 1860s originally memorialized Hannah and her husband. It’s now broken, with the top part missing. But we know Edward’s name was inscribed on the top of the marker since his vital record of death lists the data source “From Tombstone” at the current plot location, and since Hannah’s name on the stone is followed by the words “his wife.”

Figure 10. Broken marble marker for Hannah Damrell

Figure 11. detail photo with Hanson’s signature lower right

The other signed marker from the 1860s was created for Captain Ira Bradford, who died in 1866 at the age of 83. As seen in Figure 12, his marble marker is in very poor condition—broken in at least 4 pieces.

Figure 12

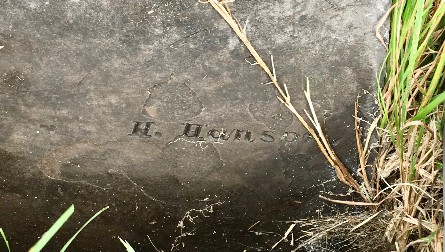

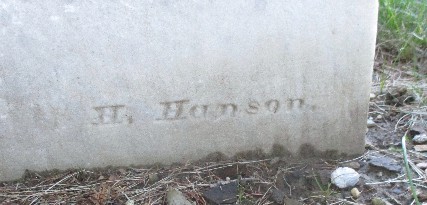

In the accompanying detail photo (Figure 13) note that the signature is “H. Hanson” followed by “Westbrook.”

Figure 13

The advertisement Henry placed in the Portland Directory in 1868 (Figure 14 and Figure 0) tells us the exact location of both his home and business. His shop was located at the north end of Deering’s Bridge, which at the time crossed over the southwestern section of Back Cove into the town of Westbrook.3 No bridge exists today since that part of Back Cove was filled in to create Baxter Boulevard. But if we overlay a present day map over an earlier map that shows Deering’s Bridge, we find that the Hanson stone shop was located about where the large Hannaford grocery store is now. This area was known as “Westbrook Point.”

Figure 14 (Text description under Figure 0)

Around the time these two marble markers were produced, Sarah Hanson delivered her seventh child, George Henry Jarvis Hanson, in February of 1866.

During this decade, Henry appears to have entered into a couple of short-lived partnerships. The 1860 Almanac & Register (published by C. Augustine Dockham) contains a list of marble workers. Among the seven businesses we find “Rumery & Hanson” at 212 Cumberland Ave. But Rumery’s name never appears again, and Henry is listed alone in the 1863/64 directory.

Then, in the 1866/67 directory, we find two listings: “Hanson, Henry (& Swett) marble worker,” and “Swett, Marshal (& Hanson) marbleworker” both with a business address of 26 Preble St. Henry’s home address was 77 Brackett; Marshal’s was St. John. Swett’s listings in the preceding and following directories have him working as a currier and a cooper. Then, in the 1869 directory, Henry is again listed alone.

The 1870s Markers

Two more signed markers we’ve found were created in the 1870s. Mary Wiggin died in 1871, at the age of 79. Her marble marker is intact, but heavily eroded (Figure 15), making it a bit of a challenge to read the full inscription. But the signature, “H. Hanson” is present where expected, at the lower right just above ground level (Figure 16).

Figure 15

Figure 16

By the middle of the 1870s, Henry Hanson was apparently doing quite well. He’d been cutting stone in Portland for 25 years, he and his wife were raising seven children, and he had moved the family and his business to Weymouth Street.4 But in 1876, personal tragedy struck, when his son Charles died of “dropsy” (edema) at the age of 16. Charles was buried in a family lot at Evergreen Cemetery overlooking the duck ponds.

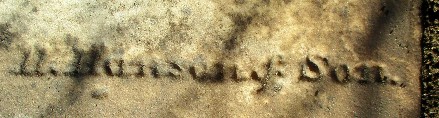

That same year, Henry created a marker (Figure 17) for Mary Shaw, who died at age of 74. Today, her marker is in dire need of attention. It’s broken, laying flat in the ground, and is being lost to the encroaching sod. Still, from the fragment that is still visible, we find Hanson’s signature. Note it reads “H. Hanson & Son” (Figure 18).

Figure 17

Figure 18

The son was Henry’s first boy, William Henry A. Hanson, who was then about 26 years old. The first mention of an occupation for William was six years earlier, in the 1870 census. He was 19 years old then, still living at home with his parents, and working as a fresco painter. This census also confirms that he was born in New York (during Henry and Sarah’s very brief stay there). So Henry must have changed careers—from frescos to marble—to work with his father awhile.

In a springtime 1876 issue of the Portland Daily Press, William was named along with his father on the company advertisement (Figure 19). In the 1877 directory, William was still a marble worker. But soon after, he moved to Boston, where he returned to his former occupation as a fresco painter. He contracted pulmonary tuberculosis and died in Boston at the age of 39. After William moved to Boston, Henry’s business listings never again included a partner’s name.

Figure 19

- H. Hanson & Son,

Manufacturers of Monuments, Tablets, Grave Stones and Granite Work.

Manufactory at No. 907 Congress St., West End, Portland, Maine.

All orders promptly attended to.

Henry Hanson.

Wm. H.A. Hanson.

Apr17, d6m

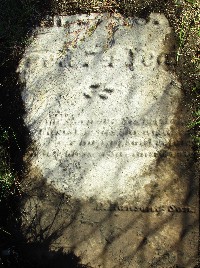

The Sixth Signature—A Fragment

The last known marker found at Eastern Cemetery (so far... we’re always looking!), is not assigned to anyone, since it consists only of a marble fragment containing the signature “H. Hanson.”

Figure 20

The fragment was originally found and photographed in Section C of the cemetery, but has eluded my efforts to locate it again in order to pinpoint an approximate plot location. Perhaps during future conservation work we will find it again and rescue it from permanent loss. If luck is on our side, we will also recover enough of the rest of the stone nearby to allow us to piece it back together, assign it to its rightful owner, and return it to the correct plot.

The Leafy Flourish

Though marble was the material of choice during Henry Hanson’s productive years, it is too soft of a stone to survive for long. All of Hanson’s signed markers have issues. Still, enough remains on some of them to allow for study of his carving style.

Three of the six markers in this collection include a leafy flourish centered at the end of the inscription. The markers for Hannah Damrell, Ira Bradford, and Mary Shaw feature this decoration (Figure 21, Figure 22, and Figure 23—some are heavily eroded). With the stem to the left and four or more small leaves sprouting off to the right, this could have served as a sort of maker’s mark. It’s a simple and small design that adds a bit of charm to the inscription panels on Hanson’s markers, which otherwise lack decorative elements such as urns and willows in popular use by other carvers in the midcentury.

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23

If it’s true that this was Hanson’s “signature mark,” then there are other markers found at Eastern Cemetery that could very well be his. At least four more markers there—three marble and one slate—feature this leafy flourish. Their dates, 1848 to 1865, fit within the time Hanson was cutting stones in Portland. Two of them are shown here; a slate (Figure 24) and a marble (Figure 25).

Figure 24

Figure 25

Through the Turn of the Century

Portland directories through the 1880s and 1890s show that Henry Hanson continued carving into his seventies. The 1892 directory is the last which lists him as a marble worker; in 1893, at the age of 73, he was residing at the Home for Aged Men at 117 Danforth Street. Directories place him there for the rest of his life. The US Census for 1900 has him at the Home, but contains some errors, including that he was a widower. That error is understandable, since Sarah had left Portland to live in Melrose, Massachusetts, with her daughter Nelcina and son-in-law Edwin Waterhouse. The 1900 Census for Melrose lists four generations in Edwin’s household: mother-in-law Sarah, he and wife Nelcina, two of his adult children, and two grandchildren.

Henry Hanson died on August 21, 1905, at the age of 85. Cause of death was senility. Two days later, he was buried in the family lot overlooking the duck ponds at Evergreen Cemetery in Portland. Only one large modern granite monument is on the family lot. It names William & Priscilla on the front side; the reverse names Henry & Sarah, plus Charles and George.

Family Notes

Henry and Sarah had at least seven children, three sons (all of whom predeceased them) and four daughters. All seven reached their teenage years; some lived long lives. Sarah (Shaw) Hanson died seven years after Henry in 1912, at age 84. She was buried in the family lot alongside Henry and their three sons. Notes about the children follow:

| Annie Maria | 1847 | unknown | Married Wallentine Kailer in Portland in 1866. He was an Irish immigrant, working as a "hay weigher" according to the 1870 census. She appears in the 1880 census, but I lost track of her after that. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| William Henry A. | 1850 | 1890 | family lot at Evergreen Cemetery | Married Priscilla T. Woodman; they had at least four children. He initially worked as a fresco painter, but then worked with his father for a short while at the stone shop. He died too young—at age 39—in Boston of "phthisis" (pulmonary tuberculosis) but his body was brought back to Portland for burial. Priscilla died 40 years later, in 1930, and was buried at Evergreen with William. |

| Sarah Elizabeth | 1852 | unknown | She appears in the 1870 census with her parents, but I’ve not been able to track her down further. | |

| Nelcina Ester | 1854 | 1926 | Married Edwin Waterhouse in Massachusetts in 1877 and had children and grandchildren in her household in later years. She hosted her mother at their Melrose, MA home for a few years when Henry was at the Home of Aged Men in Portland. | |

| Charles Albert | 1860 | 1876 | family lot at Evergreen Cemetery | Died at age 16 of dropsy (edema). |

| Henrietta Otilla | 1862 | unknown | Married Franklin H. Jones in 1884, but I lost track of her after that. | |

| George Henry Jarvis | 1866 | 1883 | family lot at Evergreen Cemetery | Died of consumption at age 17. |

Eastern Cemetery Plot Locations of Signed Markers

This table provides plot locations and other details about the six markers signed by Henry Hanson, as well as the other four markers that were signed by their makers.

| Damrell | Hannah M. | 1863 | B-11-05 | Marble. Conserved, though top piece of the marker is missing. Has leafy flourish. | H. Hanson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dodge | Sally and Israel | 1843 and? | J-46 | Purple slate. Heavily flaking. Broken in at least two, with bottom section well below ground. | H. Hanson |

| Wiggin | Mary | 1871 | K-127 | Marble. Eroded and needing cleaning. | H. Hanson |

| fragment | ? | ? | C-51 (possible vicinity) | Broken marble in ground, with encroaching sod. Unsure where this fragment now is. | H. Hanson |

| Bradford | Capt. Ira | 1866 | B-09-35 | Marble. Marker is broken, in at least 4 pieces stacked at plot. Has leafy flourish. | H. Hanson Westbrook |

| Shaw | Mary | 1876 | C-244 | Marble. Broken and in the ground. "Age 74" shows clearly on the fragment and matches record in Jordan for C-244. Has leafy flourish. | H. Hanson & Son |

| Murch | Albert N. | 1857 | L-58 | Marble. Conserved, in good shape. | Hunt & Jewett |

| Mitchell | Catharine | 1846 | A-08-09 | Marble. Conserved, in good shape. | R. Smith |

| Mountfort | Edmund (& 7 others) | 1837 | D-31 | Marble. Conserved, in good shape. | Thompson |

| Bradford | Hannah | 1872 | B-09-36 | Marble. Conserved, though heavily eroded. [Coincidentally, she was married to Captain Ira Bradford listed in this table, whose stone also contains a carver signature.] | W. H. Merrill Deering |

Continuing Work

As more gravestones are recovered from underneath the sod at Eastern Cemetery during our conservation work, we’ll look for additional signatures. Stonecutters were artists, each with his own unique style. Studying signed gravestones helps us differentiate one carver from another. As the collection of signed markers grows, we gain confidence in assigning those markers lacking signatures to the correct carvers of the period.

Specific letters and numbers, patterns of inscription wording, depth of carving and decorative elements all help in the process of identifying carvers and then sorting gravestones by carver. Sometimes a carver used a unique design that becomes a "signature mark" that can be used—in lieu of an actual signature—to assign the stone to him.

Henry Hanson worked with stone for 40 years, and indeed left his mark: the leafy flourish. But with such a small sample known to date, a more in-depth survey at Eastern Cemetery is needed to identify additional markers with his design (with perhaps some careful digging around a representative sample of them to search for his signature). Until that work is pursued, we can appreciate the beautiful simplicity of the mark he left behind.

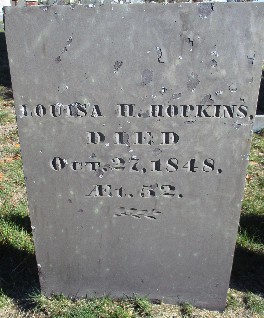

Figure 26. Detail of the leafy flourish from the slate marker memorializing Louisa H. Hopkins (died 1848). Believed to be the work of Henry Hanson.

Sources

Description and PDF version: Henry Hanson: A Marble Worker Leaves His Mark

- Ancestry.com (Vital records, Census records, Immigration files, etc.)

- Find a Grave.com

- Collections of Maine Historical Society. (Directories, newspapers)

- Barry, William David and Anderson, Patricia McGraw. Deering—A Social and Architectural History, Greater Portland Landmarks, Portland ME: 2010.

- Jordan, William B. Jr. Burial Records, 1717-1962 of the Eastern Cemetery Portland, Maine. Westminster, Maryland: 2009.

- Portland. Greater Portland Landmarks, Portland ME: 1972.

References

1 Advertisements, directories and other documents use three versions: stonecutter, stone cutter, and stone-cutter. I use stonecutter in this paper, unless specific context demands another spelling. back to text 1

2 The Dash was active during the War of 1812. back to text 2

3 Today’s Back Cove and North Deering neighborhoods were from 1814 until 1871 within the town of Westbrook. In 1871, Deering separated from Westbrook, but just 28 years later (in 1899) was incorporated into Portland. back to text 3

4 Weymouth Street runs for a couple of blocks, about from the Portland Exposition Building to Maine Medical Center’s main parking garage. back to text 4