Mortality and Memorialization in Portland at the Time of Statehood

Eighth in a series of Occasional Papers about Eastern Cemetery in Portland, Maine

by Ron Romano

© 2020

Figure: Detail of gravestone inscription (1820) at Eastern Cemetery for Mrs. Rebecca Mitchell

Carved by Abel Davis

Many are celebrating Maine’s bicentennial in 2020 by offering details about what life was like in Maine in 1820. This paper takes a look at what death was like in 1820—specifically in Portland and at its sole public burying ground at the time, Eastern Cemetery. It examines the number of deaths in Portland at the time of statehood and breaks the data into a variety of categories. Gravestone makers of 1820, with examples of their work, are discussed along with causes of death and burial practices of the time. Also included are compelling stories discovered about the locals who died the year that Maine separated from Massachusetts to become the 23rd state.

Contents

- Part 1: The Bill of Mortality for Portland

- Part 2: Deaths that Occurred Elsewhere

- Part 3: Eastern Cemetery

- Table of the 153 people found in death records for Portland in 1820

- Sources

Part 1: The Bill of Mortality for Portland

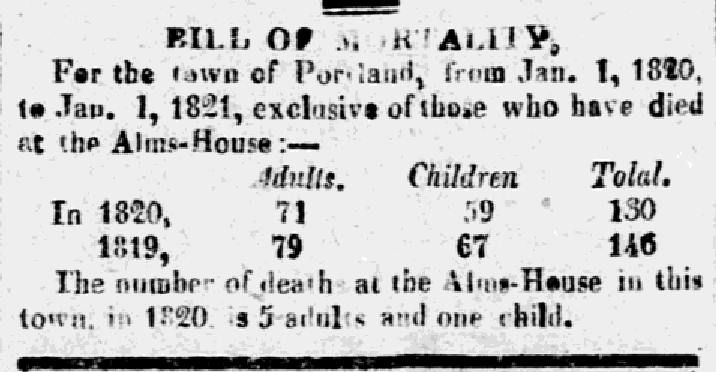

My examination of the year 1820 starts with a notice that was published in the January 9, 1821, Portland Gazette newspaper. There we find the 1820 Bill of Mortality for the town.

Figure 1.

- BILL OF MORTALITY

For the town of Portland, from Jan. 1, 1820, to Jan. 1, 1821, exclusive of those who have died at the Alms-House:—

In 1820, Adults 71, Children 59, Total 130

In 1819, Adults 79, Children 67, Total 146

The number of deaths at the Alms-House in this town in 1820 is 5 adults and one child.

It’s curious that the few deaths recorded in 1820 at the Alms-House were separated from the rest. But what we see is that 136 people (130 + 6 Alms-House) were recorded as dying in Portland in 1820, or about one death every three days. According to the fourth US census taken in 1820 there were just over 8500 people living in Portland. Therefore, the death rate in 1820 was 16 per 1000 residents; according to the Maine Department of Public Health, today’s death rate per 1000 in Maine is 9.8.

My first challenge was to identify those 136 people, and I cast a wide net for this exercise. I went page-by-page through Bill Jordan’s published burial records—as well as the accompanying Record of Interments—in order to find anyone who had a death year listed as 1820. I found 67 such entries in his book on Eastern Cemetery and one in his book on Western Cemetery.

I then looked for the weekly death notices in all 52 editions of the Gazette newspaper, which published every Tuesday in 1820 (I looked at the January 1821 papers as well, in order to catch any late reports of December deaths). A second newspaper, the Weekly Eastern Argus (hereafter just Argus), was published in Portland that year, and I found 44 of its 52 editions. I noticed that for the most part, Argus listings were duplicate to the Gazette, although sometimes one paper carried a death notice the other hadn’t. I also sporadically checked other Maine newspapers published in 1820, since they sometimes included deaths in Portland. But I did not do an exhaustive search of papers published outside Portland; the ones I checked yielded only duplicate listings.

I visited Maine Historical Society to review microfilmed records of deaths in Portland in 1820. Some of those records are available in Ancestry.com's collections. I also explored all of Portland’s cemetery listings on Find a Grave.

Then Westbrook, now Portland

It’s important to note here that in 1820 Portland’s reach was limited to the peninsula; the area inland from the town boundary was then called Westbrook. I did find some 1820 burials in the “formerly Westbrook but now Portland” cemeteries. Those records wouldn’t have been part of the 1820 Bill of Mortality for Portland and so I excluded them from my study, but since the cemeteries are today part of the city, I note them here and include them in the table at the end of the paper. There are 13 such records, as follows:

- Bailey Cemetery — 1 record

- Fobes Street Cemetery (also known as Maplewood) — 3 records

- Pine Grove Cemetery (now part of Evergreen) — 2 records

- Sawyer-Knight Cemetery — 3 records

- Stroudwater Burying Ground — 4 records

As I was building the spreadsheet for my analysis, I researched each person on the list on Ancestry.com, checking family histories, vital records, census data, and related materials. Spirits Alive (the non-profit friends of Eastern Cemetery) has a large collection of transcription forms which document the details of gravestones found there. Those forms were useful to me in verifying the final resting place of some of the people who’d died in Portland in 1820.

As noted above, I had cast a wide net to find as complete a list as possible. When I pulled the net in, I’d collected records for 141 people (including 3 at the Alms-House)—just five more than the 136 reported in the Bill of Mortality. In thinking about the data now, I make an assumption that the writers of the 1820 Bill of Mortality recorded deaths literally as noted “for the town of Portland.” In other words, those who were from Portland but died elsewhere were likely excluded from the tally on the Bill. I found 23 such records, and they’re covered in detail in Part 2, but when I set those names aside, my list reduced from 141 to 118. So, I can account for 118 of the 136 people reported in the 1820 Bill of Mortality, or about 87% of the total.

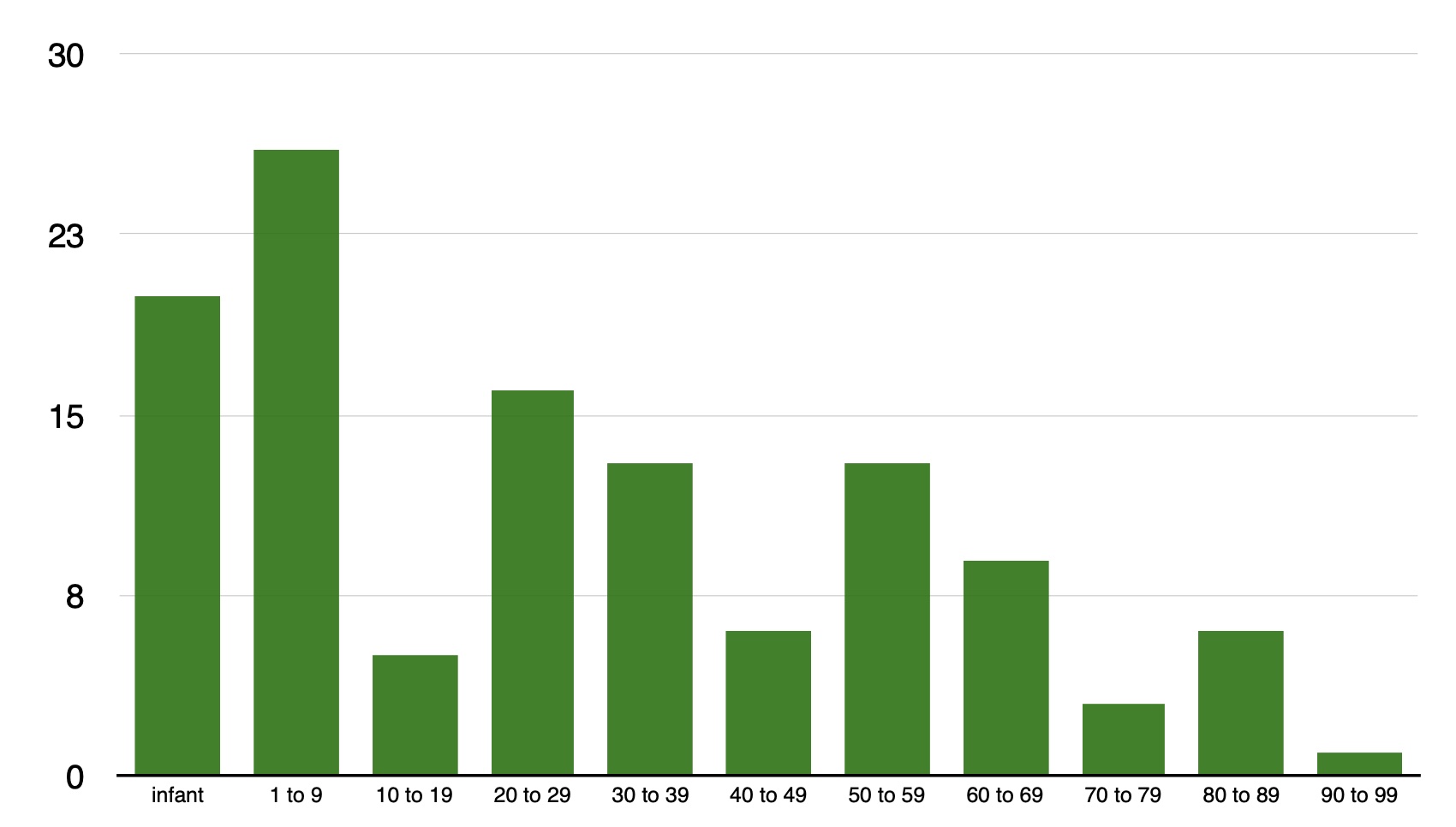

Age distribution

The Bill of Mortality separated adults and children, but did not define the age of children. For my analysis of the data, I considered children to be newborn through age 19 and adults 20 and over. The following chart (Figure 2) shows the ages of the 118 confirmed deaths in Portland in 1820.

Infants accounted for 20 of the 118, or 17% of the total. There were 26 deaths recorded for children aged 1 through 9 (22% of the total), and five for children in the age range of 10 through 19. Together, I found that 43% of all deaths accounted for in Portland in 1820 were children.

Chart 1: Age distribution of 118 confirmed deaths in Portland in 1820

Figure 2.

- Bar graph representing 12 age groups. 1 to 9 is the tallest: between 23 and 30. 90 to 99 is the shortest. Under 8: 10 to 19, 40 to 49, 70 to 79, 80 to 89, 90 to 99. Between 8 and 15: 30 to 39, 50 to 59, 60 to 69. Between 15 and 23: infant, 20 to 29.

Sex and Race distribution

With respect to sex of the 118 confirmed deaths in Portland, there were 59 males and 51 females. Eight children were not named or identified in a way as to determine sex; a typical example of this was in the February 8th Gazette’s death notices: “In this town…a child of Mr. Enos Merrill, aged 13 months.” Because the census was taken after this child’s death, and no vital record of birth located, there’s no way to assign sex. But in a couple of cases I was able to narrow things down. For example, in the September 26th Gazette, there was this listing “In this town… a child of Mr. Joseph Crockett, aged 10 months.” The census was recorded in August—a month before he or she died—so this child was included in the census. Mr. Crockett’s 1820 census record had him in Portland as the head of a household of five people, including three male children under age 10. The lack of any female kids in his household allowed me to assign this unnamed child as “male.” Later in the century, census takers began to record the names, ages, and sex of all members of a household; but this was not the case in 1820, so there are a few unknowns in the data set.

With respect to race, three of the 118 were identified as African American. They are:

- John Flood, age 28, who died August 28. His death notice, published in the September 5th Gazette noted “At the Alms-House in this town… on the 28th, John Flood, a man of color, aged 27.”

- William Lloyd, age 22, who died around October 15. His death notice, published in the October 17th Gazette noted, “Drowned—In this town, William Lloyd, a man of colour, aged 22.”

- Hager (perhaps Hagar) Boaz, age 51, who died around November 4th. She was not identified in the newspapers as a person of color, but I confirmed this in other records.

The Gazette had carried this notice on November 7th: “In this town, Mrs. Hager Boaz, wife of Mr. James Boaz, aged 51 years.” The following week the Argus had this: “In this town… Mrs. Hagar, wife of Mr. James Boaz, aged 57 years and 8 months.” In researching her records, I found that her husband was listed in the 1820 and 1830 Portland censuses as a person of color (as Bowes and then Boas). In the 1834 Portland Directory, he was named as a person of color living on Adams Street (Figure 3, correctly spelled, midway down the list).

Figure 3.

- Directory.

Ward No. 7.

York Charles, farmer, h oxford near the alms house

York Reuben G. ship broker, head long whf. h winter.

People of Color. Ward No. 1.

Ackrow Lucy, widow, hancock

Adams Hannah, widow, washington

Alexander Henry, mariner, h hancock

Anderson Elsey, widow, hancock

Ball James, mariner, h sumner

Boaz James, pensioner, h hancock

Brown William, mariner, h hancock

Cane Joseph, soap-boiler, h mount joy

Clark Thomas, mariner, h hancock

Dates Titus, mariner, between hancock and king

Davis James, laborer, h washington

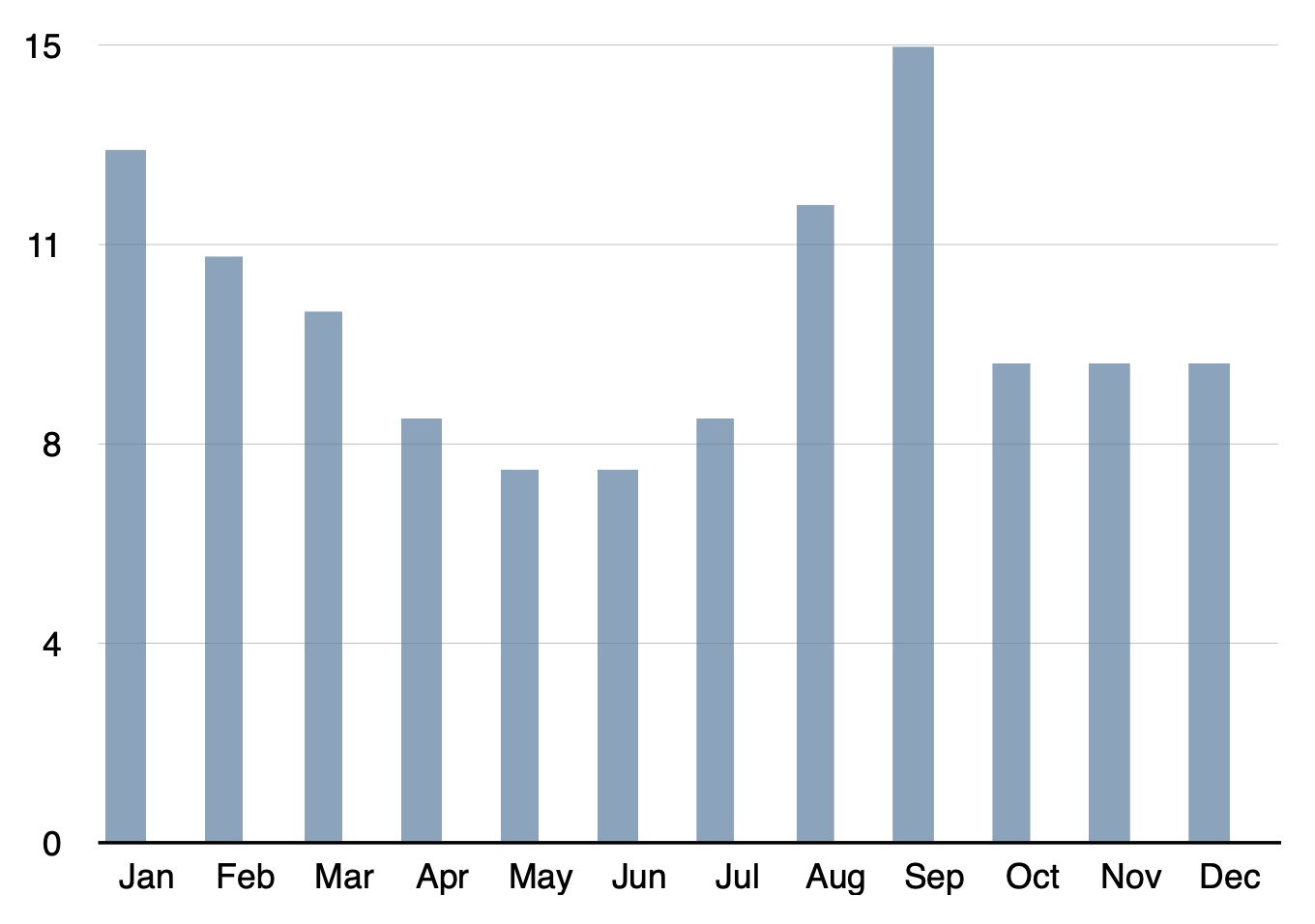

Distribution by month

As I went through the process of documenting deaths in Portland in 1820, I wondered if I might find a spike that would suggest the presence of a particularly challenging infectious disease or disaster. Instead, I found (Figure 4) that the deaths occurred relatively evenly across the months, with the least number occurring in May and June (7 deaths each month) and the most occurring in September (15 deaths that month).

There was a bit of a dip in deaths during late spring/early summer, and then an increase at the end of the summer, but with an average monthly death rate of 10 people, none of the months really wavered too far from the average.

Chart 2: Distribution of 118 confirmed deaths in Portland in 1820 by month

Figure 4.

- Graph with bars representing 12 months. May and June were the lowest: between 4 and 8. September was the highest: 15. Between 11 and 15: January, August. Between 8 and 11: February, March, April, July, October, November, December.

Causes of death

Vital records of death were found for at least four dozen people in Portland in 1820, yet none of them listed cause of death. Rarely was cause of death given in the 1820s newspapers. If anything, the death notice might offer a hint with “died very suddenly,” which suggests an unexpected passing but not the exact cause. Few clues are found in these records of any epidemic disease or even the diseases one might expect to find prevalent at the time. In the September 12, 1820, Argus, at the end of the usual list of those who had died in the area in the past week, there was a paragraph that identified common causes of death in two northeast cities. Perhaps these were also common causes in Portland? For New York City, in order of most-to-least prevalent, was: consumption, convulsions, dysentery, infantile flux, and cholera. For Philadelphia, the list was: consumption, convulsions, dysentery, cholera, malignant fever, and other fever.

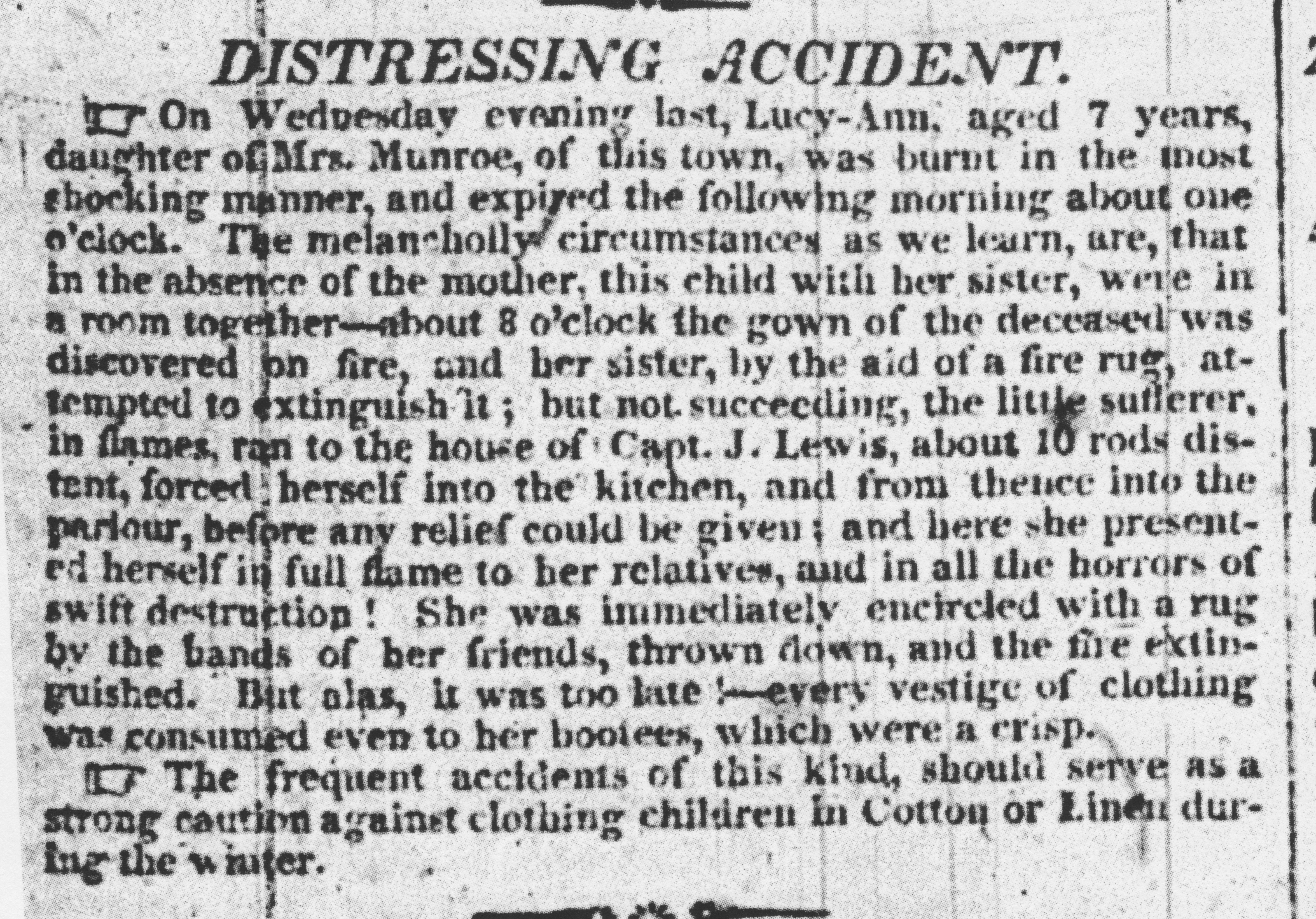

One of the first deaths in Portland in 1820 was also one of the saddest and most shocking. The story was covered in a half-dozen newspapers in Maine, as well as in New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, and Washington DC. Lucy-Ann Munroe died January 5th at age 7 in what was described as a “distressing accident.” The Argus carried the story in its January 11th edition (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

- DISTRESSING ACCIDENT.

On Wednesday evening last, Lucy-Ann, aged 7 years, daughter of Mrs. Munroe, of this town, was burnt in the most shocking manner, and expired the following morning about one o’clock. The melancholy circumstances as we learn, are, that in the absence of the mother, this child with her sister, were in a room together—about 8 o’clock the gown of the deceased was discovered on fire, and her sister, by the aid of a fire rug, attempted to extinguish it; but not succeeding, the little sufferer, in flames, ran to the house of Capt. J. Lewis, about 10 rods distant, forced herself into the kitchen, and from thence into the parlor, before any relief could be given; and here she presented herself in full flame to her relatives, and in all the horrors of swift destruction! She was immediately encircled with a rug by the hands of her friends, thrown down, and the fire extinguished. But alas, it was too late—every vestige of clothing was consumed even to her bootees, which were a crisp.

The frequent accidents of this kind, should serve as a strong caution against clothing children in Cotton or Linen during the winter.

Noted above was the October drowning of William Lloyd, age 22. He was the last of three such deaths reported in Portland that year. The others occurred in July, just a day apart, and were reported in the July 11th issue of the Gazette as follows:

Drowned - on Wednesday last, in back river, Thomas, son of Mr. Abraham Osgood, aged 9 years. Whilst playing on the Stringers of Deering’s bridge, he fell into the river, and before he could be extricated was drowned past recovery.

“Drowned - In Back-Cove River, in this town, on Thursday last, Mr. Richard Bartlett, aged 35. He arrived in town two days before from St. John N. B. with a view of establishing himself in the Tailoring business. Thursday afternoon he with another man and boy went out in a float to fish—Mr. B. who has a wife and three children at St. John, was drowned—the other two held onto the float and were saved.

The Argus covered the drownings as well, adding detail regarding Mr. Bartlett’s final minutes: “…when by some accident (the float) upset—he being the only one acquainted with swimming attempted to reach the shore and failed—the others were saved by clinging to the boat.”

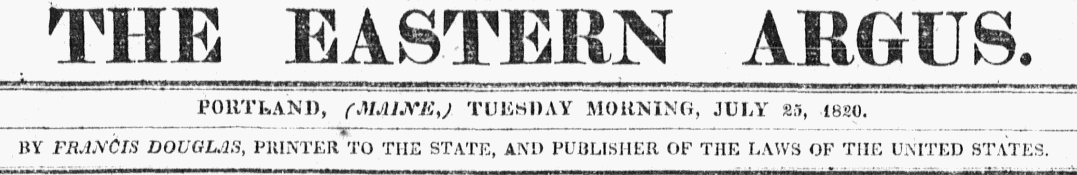

Francis Douglas

The majority of people who died in Portland in 1820 were ordinary citizens, shopkeepers and tradesmen, lawyers and veterans, mothers and children. Of the 141 names that appear on my roster, the one whose death stands out the most is Francis Douglas, a printer by trade who was editor and publisher of the weekly Eastern Argus newspaper.

Figure 6.

- The Eastern Argus, Portland, (Maine) Tuesday morning, July 25, 1820. By Francis Douglas, printer to the state, and publisher of the laws of the United States.

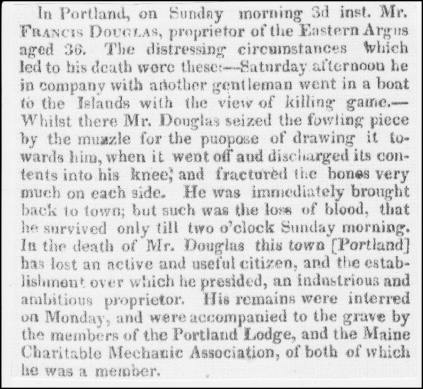

Certainly the accident that caused his death was tragic and newsworthy. Perhaps because of his standing as a newspaper publisher, the accounting of the accident was carried by so many papers. I found his death reported in 15 of the 23 US states, as far west as Illinois and as far south as Georgia. The Portland newspapers carried a more lengthy version; the copy below (Firgure 7) is typical of the versions printed in out-of-state papers.

Figure 7.

- In Portland, on Sunday morning 3rd inst. Mr. FRANCIS DOUGLAS, proprietor of the Eastern Argus aged 36. The distressing circumstances which led to his death were these:—Saturday afternoon he in company with another gentleman went in a boat to the Islands with the view of killing game.—Whilst there Mr. Douglas seized the fowling piece by the muzzle for the purpose of drawing it towards him, when it went off and discharged its contents into his knee, and fractured the bones very much on each side. He was immediately brought back to town; but such was the loss of blood, that he survived only till two o’clock Sunday morning. In the death of Mr. Douglas this town [Portland] has lost an active and useful citizen, and the establishment over which he presided, and industrious and ambitious proprietor. His remains were interred on Monday, and were accompanied to the grave by members of the Portland Lodge, and the Maine Charitable Mechanic Association, both of which he was a member.

Douglas was in his thirties, and married but with no children at the time of his death.

The accident that led to his passing occurred about ten miles from Portland, but his friend was able to row him back to town. Surgeons were called and intended to amputate his leg, but the significant loss of blood from the accident weakened him such that they could not proceed with the operation, and his death came about 10 hours after the accident.

In his own newspaper, his friends ended the report of his death with this: On Saturday morning the sun rose on but few men with fairer prospects of a happy, prosperous and lengthened life, and in a few hours the whole area was overcast with the shadows of death.

Part 2: Deaths that Occurred Elsewhere

As noted above, records of 23 deaths were found for people with ties to Portland who had died elsewhere in 1820. A breakdown and details follow.

Out of town (but in Maine)

Three records were found for Portlanders who died outside the city. In January, James Bryant died while visiting a friend in Lisbon, Maine. As reported in the Argus:

At the house of Maj. John Rowe, in Lisbon, Me. Mr. James Bryant, late of Portland, aged 64—he came into the house in his usual health, seated himself in a chair, and expired instantaneously, without struggle or a groan.

Two men died in New Gloucester. In February, James Megquier died there at age 37. Though the death notice in the paper said he was “of New Gloucester,” there is a burial record for him in Jordan’s book at Eastern Cemetery. As well, his wife, Rebeckah, was buried at Eastern Cemetery when she passed in 1846. They are memorialized on a shared gravestone that is in damaged condition. Then in March, Captain Thomas L. Roach died in New Gloucester. He was 55. Like the Megquiers, he and his wife Hannah share a gravestone at Eastern Cemetery. She died in 1831.

Out of state

Four records were found for Portlanders who died outside the state. In July, Dr. Martin Herrick died in Lynnfield, Massachusetts. He was 73 and served as a surgeon in the Revolutionary War.

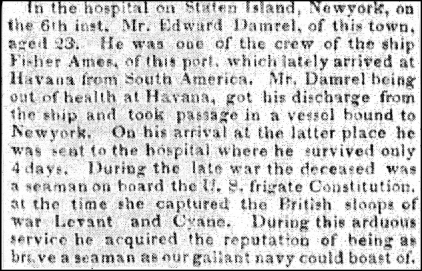

In August, Edward Damrel died in Staten Island, New York at the age of 23. The August 15th Gazette honored him for his service on the US Constitution when reporting his death (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

- In the hospital on Staten Island, New York, on the 6th inst. Mr. Edward Damrel, of this town, aged 23. He was one of the crew of the ship Fisher Ames, of this port, which lately arrived at Havana from South America. Mr. Damrel being out of health at Havana, got his discharge from the ship and took passage in a vessel bound to New York. On his arrival at the latter place he was sent to the hospital where he survived only 4 days. During the late war the deceased was a seaman on board the U.S. frigate Constitution, at the time she captured the British sloops of war Levant and Cyane. During this arduous service he acquired the reputation of being as brave a seaman as our gallant navy could boast of.

Also in August, Mr. Tilley Munroe, age 44, died in Norfolk, Virginia. He had been working at the Portland firm of Munroe & Tuttle. He was likely buried in Virginia.

Also in Norfolk but in September, 19-year-old Josiah Corry died. He was a ships-mate on the schooner Comet. He was certainly buried there (or at sea) although he is memorialized on his mother Esther’s gravestone at Eastern Cemetery.

Out of country

Nine records were found for Portlanders who died outside the country. There is probably some overlap with the final category found below, “lost at sea” but for those not specifically listed as lost at sea, I report them here.

Cuba was a particular hot-spot in 1820, with six deaths reported (plus Edward Damrel just discussed, who had become ill in Havana but died in New York on his way home).

- On July 17, Stillman Jordan, one of the crew of the brig Statira died in Havana. The Jordan family was well represented in Portland, but it is just my assumption that Stillman was living in Portland at the time. The ship was “of this port” which is why his death was reported.

- On August 3, William Drinkwater, mate on the brig Moro, also died in Havana. His death notice confirmed that he was “of this town.” He was 25.

- On September 14, Captain Charles Cushman died “very suddenly” at St. Jago de Cuba. He was captain of the brig Delegate, “of this place” (that is, Portland). The newspaper noted his age of 25 and said, “He was a worthy, active young man; his death is much lamented.”

In August, three more sailors died in Cuba from the same ship. The Argus reported their deaths in its September 12th edition:

In Havana, Aug 6, William Wilson, George W. Elwell, and Robert Stetson, all of Portland, belonging to the brig Cordelia, Capt. Tolman. The above named seamen were taken sick on Thursday the 3rd, and died on Sunday evening, within 3 hours of each other. So rapid was the progress of their disorder, that medicine had no effect whatever.

Havana is located on the north coast of Cuba, due south of Tampa, Florida; St. Jago de Cuba, now called Santiago, is a port at the opposite end of the island on the south coast, due north of Cartagena, Colombia. I found an article in the June 30th Argus that reported Yellow Fever (also referred to as malignant fever) had taken the lives of some sailors on a ship that had come back to New England after being at the port of St. Jago de Cuba. Many others aboard, including the captain, had become sick but ultimately recovered. The vessel was kept at quarantine for a while, and thoroughly cleansed before returning to service. It is likely that some of the seven Portland men discussed here were taken down by Yellow Fever as well.

Beyond Cuba, three other international deaths were found in the 1820 newspapers:

- In January, Ebenezer Knox, age 36 and “formerly of Portland” died in St. Thomas.

- In September, an infant child of Eben F. Douglas (also “formerly of this town”) died in Hamilton, Bermuda. Mr. Douglas had owned a Portland watch shop a few years earlier, so this is another example of one who may or may not have actually been a Portland resident at the time of his death. In my effort to be as inclusive as possible, he stays on the roster of 1820s deaths.

- In November, Mrs. Rebecca Mitchell died at Grand Manan, New Brunswick, Canada. She was in her seventies. She is memorialized on a slate marker at Eastern Cemetery, though I suspect this is a cenotaph placed by relatives since it is unlikely (though not impossible) that her remains were returned to Portland.

Lost at sea

Seven records were found for Portlanders who were lost and/or buried at sea. They were all young men, aged 17 to 23, and most were sailors. The first of the seven is also the most famous. He was Franklin Alden, a relative of Rear Admiral James Alden, who was a direct descendant of Mayflower first passengers John Alden and Priscilla Mullins. James travelled the world during his storied career and has a magnificent pink granite monument at Eastern Cemetery.

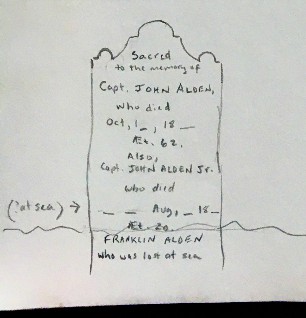

Franklin was the son of James’ brother Capt. John, and one of three of John’s sons who were lost at sea. A marble gravestone at Eastern Cemetery, shown in Figure 9, memorializes Capt. John Alden and his three sons, although Franklin’s name is now below ground as the stone has sunk over the past 150+ years.

Figure 9.

- Sacred to the memory of Capt. JOHN ALDEN, who died Oct. 19, 1833, AEt. 62.

Also, Capt. JOHN ALDEN Jr. who died at sea Aug. 3, 1843, AEt. 20

However, a copy of the drawing of the marker made during the Spirits Alive transcription project is shown in Figure 10. We can see that when the earth was dug away from the stone in order to record the inscriptions, Franklin’s name and fate were found.

Figure 10.

- Sacred to the memory of Capt. JOHN ALDEN, who died Oct. 1_, 18_, AEt. 62.

Also, Capt. JOHN ALDEN Jr. who died at sea Aug. _, 18_, AEt. 20

FRANKLIN ALDEN who was lost at sea

Other deaths at sea were as follows:

- Samuel Fogg, seaman of Portland, was lost overboard from the schooner Planter of Boston in January.

- A man presumed to be named Michael Byrne fell overboard from the sloop Hero as it was making its way to Portland from St. John, New Brunswick in January. The editors of the Portland paper asked for help in identifying the man. He may have actually been a resident of Canada.

- In March, lost from the brig Levant was Mr. Albert H. Mead of Portland, aged 17.

- From the Portland-based brig William, David Sweetser died at sea on May 13.

- In August, William Evans, age 22, died on board the ship Liverpool on her passage from Rotterdam to St. Ubes, Portugal.

- In September, on his passage from St. Bart’s to Philadelphia, 17-year-old Nicholas Loring of Portland died.

But for the cenotaph placed at Eastern Cemetery for Franklin Alden, no other gravestones are known for these men who were lost at sea. As well, no vital records were found for any of them. And as noted earlier, I expect they were not included in the original tally of Portland deaths as recorded in the 1820 Bill of Mortality.

Part 3: Eastern Cemetery

With deaths occurring on average about one every three days in Portland in 1820, the town’s sole public burying ground would have been buzzing with activity. Of course, burials were possible only while the ground remained unfrozen, likely April through November; during the frigid winter, bodies would have been stored in a shed located at the burying ground or in a family’s barn if they had one on their property. In outlying areas, private family backyard burial patches were typical, but on the more crowded peninsula the public burying ground that had been established more than 150 years earlier served the townspeople well. Before we dive deeply into Eastern Cemetery, there are two other Portland burial patches to be addressed…

The Vaughan Family Cemetery

There was still one private family cemetery on the peninsula—in the west end of town where today’s Western Cemetery is located. Much of that land was at the time owned by the Vaughan family. They had set aside a small part of their land to serve as their family’s burial patch, and we know of at least ten members of the family who were interred there. Four Vaughans were buried there before 1820 and five after, but one member of the family died in 1820, and was therefore represented in the Bill of Mortality. She was Miss Elizabeth Jordan Vaughan, who died mid-January at the age of 45. While her entry in Jordan’s Western Cemetery book reads “no burial record,” I found her death notice both in the Gazette and Argus January 18th and 25th.

The Alms-House

The Bill of Mortality separated the Alms-House deaths from the rest of Portland’s deaths. In his book of burial records for Eastern Cemetery, Jordan wrote:

“In 1804, an Alms House/Town Farm was built on what is now Park Avenue… A burial ground was established in 1858 called the Alms House Yard. Burials continued to be made until 1874.”

The location of the yard was where Hadlock Field is today. Jordan published a list of 150+ names of people interred at the Alms House Yard from 1858 to 1874. In 1887, all of the bodies were removed to a mass grave at Forest City Cemetery (located in South Portland but owned by Portland). It is quite possible that burials had occurred on the Alms House property before 1858 as well. But since this is not clear, I include the three people I know of in the burials at Eastern Cemetery, assuming they would have been buried in one of the patches set aside for paupers, the friendless, and unknowns (called “Strangers Grounds.”) The three whose lives ended at the Alms House in 1820 are:

- John Flood, mentioned earlier as one of three African Americans

- Mrs. Mary Skilton, age 82, died early in June

- Mrs. Lydia Berry, age 40, died August 30. The notice of her death (Figure 11) was carried in the September 5th Gazette, but on September 9th, the Portsmouth Oracle (a New Hampshire paper) reported Lydia’s death in Portland, noting that she was of Dover, NH.

Figure 11.

- At the Alms-House in this town, Mrs. Lydia Berry, age 40. The deceased was a stranger in town—was taken sick and carried to the Alms-House on the 29th and died the 30th ult. The Master of the Alms-House was unable to obtain a correct certificate of her former residence, but understood that she was born in Dover, N.H., that her maiden name was Lydia Spencer, and that she married a Mr. Berry, of Nottingham, from whom she was divorced about 10 years since. She appeared unusually resigned in her sickness and will to depart.

Some numbers for Eastern Cemetery

Now we turn to Eastern Cemetery, starting with a few numbers. Recall the Bill of Mortality recorded 136 deaths for Portland in 1820, and I’ve been able to find 118 of them. How many of these people ended up at Eastern Cemetery? Surely the majority of them did, but only 70 of them have records proving placement there. During research I split my data sheet into three categories: confirmed burial and/or gravestone at Eastern Cemetery, presumed burial at Eastern Cemetery, and other records of death (these are the lost at sea, died out of state, and buried in other Portland cemeteries people already addressed).

In order to be considered a confirmed burial and/or gravestone at Eastern Cemetery, I looked for one or more of these:

- Published burial record in Jordan

- Portland vital record of death (often giving an Eastern Cemetery plot number)

- Find a Grave photo of a gravestone

- Spirits Alive transcription of a gravestone

- Other survey/info record

Using these parameters, 70 names qualified. Of these, 64 died in Portland and 6 died elsewhere but were memorialized at Eastern Cemetery on a gravestone (example: Franklin Alden addressed above). 61 of the 70 had published death notices in the newspapers.

A presumed burial at Eastern Cemetery was for one whose death in Portland in 1820 was reported in the paper, but for whom no vital record of death or gravestone could be found. For these people, I looked for:

- Relationship to a close relative known to be buried at Eastern Cemetery. Neal Shaw provides our example: He died February 24, and his death was reported as being “in this town…” in the newspapers of February 29 and March 4. His wife, Hepzebeth, died in 1812 and was buried in plot D-34; her grave is decorated by a Bartlett Adams-carved slate marker which names her husband. Today her gravestone exists alone; there are at least five unmarked plots on either side of hers. It is very likely Neal Shaw was buried near her, and his stone has been lost or destroyed.

- Confirmation that the family was well-represented in Portland at the time. Capt. Joseph McLellan (Figure 12) provides our example: He died July 25 at age 88, and his death was reported in local papers August 1 and 12. Capt. McLellan was called the “oldest living person in Portland at the time of his death.” He was a life-long Portland resident; his wife predeceased him by seven years and was buried at Eastern at plot H-180. More than 60 members of this family were buried at the cemetery before and after 1820. It is very likely that he was buried there as well.

- Family found in the 1820 census for Portland. Fobes Dela provides our example: His 2-year-old daughter (unnamed) died just after the 1820 census was recorded for Portland. Fobes was listed in that census living in Portland as the head-of-household of 5 people, including 3 children. He appeared in some of the 1830s directories as a grocer. Given that the Dela family was Portland-based at the time of their daughter’s death, it is very likely that she was buried at Eastern Cemetery.

Figure 12. Source: History of Gorham, ME

There are 53 people whose names appear on the list of presumed burials, 3 from the Alms- House and 50 whose notices confirmed they’d died in Portland. In total, according to my calculations, Eastern Cemetery holds at least 123 of the 136 people reported in the 1820 Bill of Mortality.

Typical burial practices at Eastern Cemetery

A study of the grave plots and gravestones of those who died in 1820 reveal some clues as to the typical burial practices of the time.

- Burials were organized in relatively straight lines. Eastern Cemetery predated the rural cemetery movement which encouraged the use of curved paths, attractive plantings, and water features. It was simply a utilitarian burial ground (and not associated with a church) on land set aside by the town to hold the remains of its people. While in the 1700s there was somewhat of a free-for-all with respect to the placement of bodies, by 1820, in order to maximize the available space, bodies were laid in relatively straight lines.

- Bodies were laid head to the west, feet to the east. This practice, with roots to the earliest settlers, allowed the deceased’s soul to rise to greet the dawn, as if rising from bed in the morning.

- Graves were often marked with both headstones and footstones. The practice of marking the borders of graves with two stones continued to about 1840, so many of the marked graves of our 1820 group followed this tradition. The photo (Figure 12.1), though not from 1820, shows a slate footstone in the foreground and headstone in the background. Inscriptions were always carved on stone surfaces facing away from the grave, allowing visitors to see who was there from either side of the grave.

- Family lots were in use. Though the town had discouraged families from holding open plots for their future use, it is apparent that some families did just that, as many graves for spouses are side-by-side, even though they may have died many years apart from one another.

- Families may still have been managing their own burials. Certainly from the time the cemetery was established in 1668, families took care of burying their own dead on their own (or paid someone to dig the grave). The town did not take on the responsibility for managing burials until many years after the cemetery was founded. Exactly when is not clear to me, so there may have been families digging graves throughout 1820.

Figure 12.1.

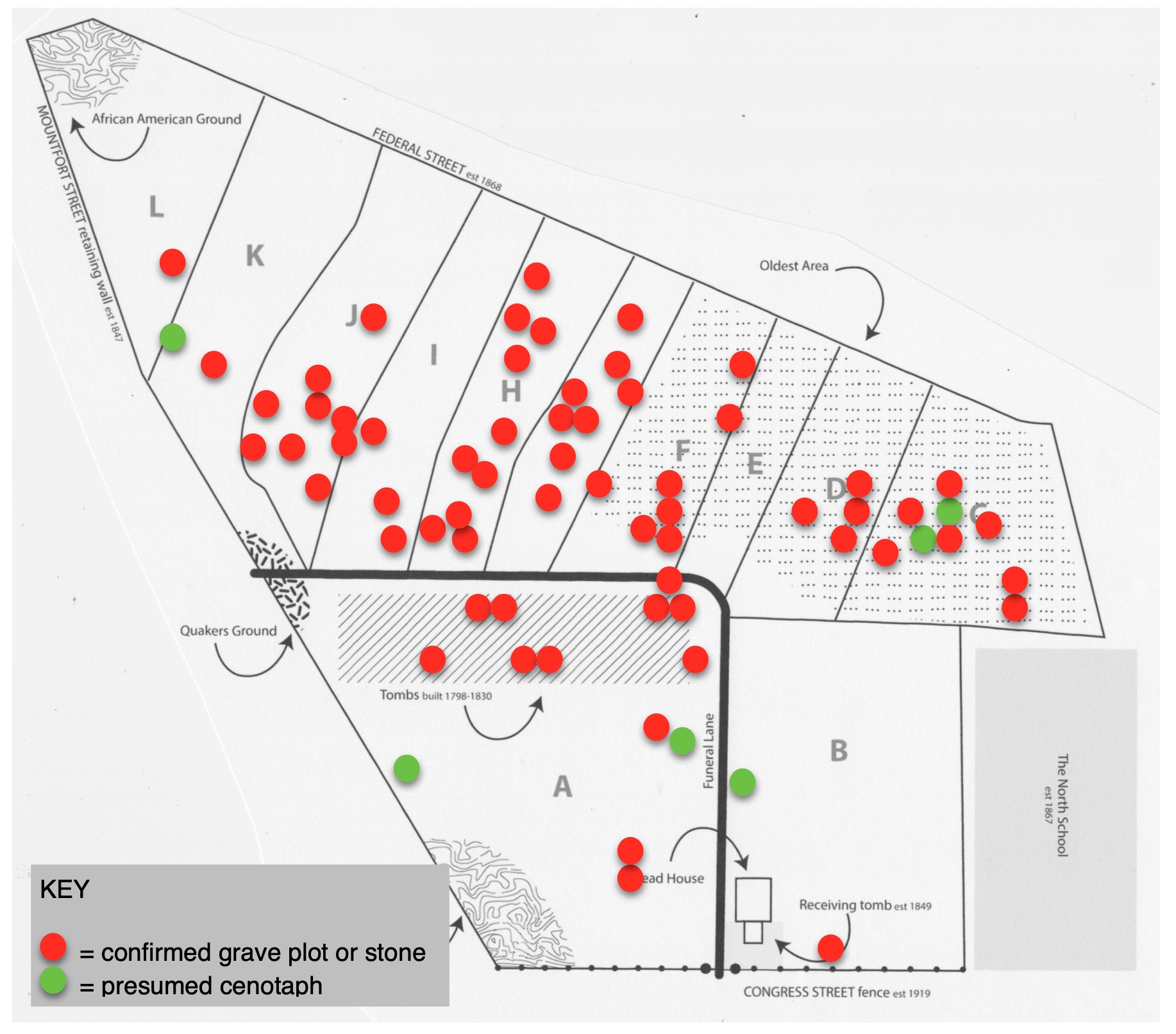

Map of 1820's graves

In 1820, the burying ground was close to capacity. By 1829, the town purchased land adjacent to the Vaughan family cemetery on the west end of the peninsula, and “Western Cemetery” was established, relieving the (now called) “Eastern Cemetery” from being the sole cemetery for the town. The entire landscape of Eastern Cemetery was open for burials in 1820; the map (Figure 11) shows the known burial locations of 69 of the 70 people on the “confirmed” list. The one exception is William Hutchinson, A Revolutionary War veteran who died April 15. He was at least 65 years old, and appears in Jordan’s book, but his grave plot location is no longer known.

Figure 13. Map source: Spirits Alive

Funerals

Funerals were organized and held soon after death, since the lack of embalming meant bodies would decompose quickly and require burial. Services were more likely held for adults and people with status in the community than for children. A funeral for an ordinary Portlander would have been held by the family at the home of the deceased or at a relative or neighbor’s home. If time permitted, it would be announced in the newspaper (note that the Portland papers were weeklies published on Tuesdays, so the only inclusion of funeral service details I found were the ones taking place the same day the paper was published).

- Miss Elizabeth J. Vaughan’s funeral was held Tuesday, January 18 “from her brother’s house this day, at 3 o’clock, P.M. Relations and friends are requested to attend the funeral without a more particular invitation.”

- Dorcas Gooding’s funeral took place at her home (the home of her surviving husband Richard Gooding), on Tuesday, February 1 at 3 o’clock.

- When Jonas Coolidge died at the age of 21 in Portland, his funeral was announced in the June 29th Gazette as “Funeral this afternoon, at 3 o’clock, from the house of Capt. William Coolidge, near Gorham Corner.”

- Catharine Mayo’s funeral took place at her home (the home of her surviving husband Ebenezer Mayo) on Tuesday, November 7 at half past 2 o’clock.

- Mrs. Mary Ann Starbird died at age 20. She was the consort (wife) of Mr. John Starbird, Jr. Her funeral was announced for Tuesday afternoon, December 12 “from Mr. Harlowe Harris,’ on Back Street, where her friends and relations are respectfully invited to attend.”

Funerals would usually include prayer and a few words from the minister. Following the service, those who wished to do so could accompany the body to the cemetery for burial.

As noted above, burials were completed soon after death. I found seven newspaper records that provided both a person’s death and burial dates. Three burials occurred just one day after death, two were done two days following death, and two occurred three days after death.

Depth of graves

There’s a commonly held belief that bodies are always buried six feet under ground. While that may be the standard today, it wasn’t the case in the early 1800s when graves were all dug by hand. We have not performed ground penetrating radar studies at Eastern Cemetery to confirm grave depths, but I asked a colleague from the national Association for Gravestone Studies who does this work to see what he has found in colonial era cemeteries he has surveyed. Nick Bellantoni told me that he has found no standard depths to the graves of the colonial period. He said depth depended partly on the soil and rock layers present, so if a gravedigger went down four feet and hit ledge or a layer of cobbles, he’d just stop digging and bury the body. He said he’s found hand-dug grave depths from the colonial days to be from three to six feet, with four feet being common.

Stonecutter Bartlett Adams

Most fans of Portland’s historic Eastern Cemetery know the name Bartlett Adams. He was Portland’s first resident stonecutter and the subject of my first book; his shop produced at least 700 of the gravestones found today at Eastern Cemetery. Bartlett had arrived in 1800 at the age of 24 and set up his shop at the corner of Federal and Fish (today Exchange) Streets.

Though he had a good number of apprentices and journeyman stonecutters working with him over the course of his 28 years here, he was the only man running such a business in Portland during his time.

In 1820, Bartlett had been married for 17 years to Charlotte Neal. They’d had seven children together, five girls and two boys, but by 1820, only three had survived: Maria was 16, Charlotte was 13, and Rebecca was 3.

Bartlett spent most, if not all, of 1820 in Boston. He and his brother Richard had opened a stonecutting business together there in 1818. In the 1820 census for Boston, we find Bartlett and his family living on Prince Street. But on October 7, the brothers dissolved their partnership (announced in a Boston newspaper, Figure 14). Richard continued to cut stone on his own.

Figure 14.

- Dissolution.

BARTLETT & RICHARD ADAMS have this day by mutual consent dissolved copartnership. Persons having accounts unsettled with them, are requested to settle with either of the Subscribers. BARTLETT ADAMS, RICHARD ADAMS

Boston, Oct. 7, 1820.

The STONE-CUTTING Business in future will be carried on by R. ADAMS, at the Old Stand, near Charles River Bridge. oct 7

Bartlett probably missed all of the statehood celebrations back home in Portland. It appears that he stayed in Boston over the winter, returning to Portland in the spring. In an ad dated March 26, 1821 (Figure 15), he announced the resumption of his Portland business at the same location as when he left in 1818. The following week, he listed the availability of half of a house (Figure 16). So, he was back in Portland for good.

Figure 15.

- BARTLETT ADAMS, STONE CUTTER, Opposite the Old Methodist Meeting-house, in FEDERAL STREET, Having resumed his business, offers for sale a large quantity of white and dove marble, slate and free STONE, suitable for Tomb and Grave Stones; hearths, jambs, and mantels; garden rolls; paint mills; flags and millers; Currier’s stones; grind stones; thresholds; window caps and sills, ∓c. Orders from any part of the country, for any work in his line, executed at short notice and on reasonable terms. Portland, March 26, 1821. 3w

Figure 16.

- One half of a two story DWELLING HOUSE to let. Apply to BARTLETT ADAMS

April 2.

Even though Bartlett was not in Portland cutting stones in 1820, I found three of his markers at Eastern Cemetery that hold the 1820 date. These are called backdated markers, and they’re quite common for a variety of reasons. People might not have had money, they might have been grieving and unable to attend to the task of getting a stone, or they might have a stone made soon after one member of the family died but would add other names of the family who’d died in previous years to the marker as well.

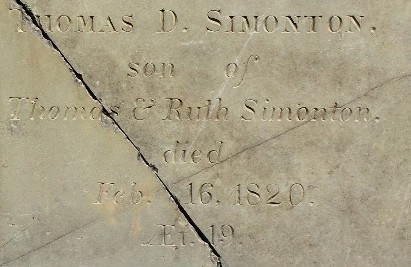

Bartlett Adams carved three markers with 1820 dates. Detail pictures are shown below (Figure 17a and b) for a slate for Thomas D. Simonton. The urn on this one is particularly unique, but shows his artistic flair. Note too the precision of his lettering and numbering.

Figure 17a. Photo courtesy of Diane Brakeley

Figure 17b. Photo courtesy of Diane Brakeley

- THOMAS D. SIMONTON, son of Thomas & Ruth Simonton, died Feb. 16, 1820, AEt. 19

Stonecutter Elias Washburn

While in Boston with his brother Richard, Bartlett left his Portland shop in the hands of his 22-year-old nephew, Elias Washburn. Elias was the son of Bartlett’s sister Lucy and her husband Bildad Washburn, an accomplished stonecutter himself. Three of Bildad and Lucy’s sons—Ira, Alvan, and Elias—became stonecutters. All three worked at Bartlett’s Portland shop; Alvan and Elias both ran the shop. Alvan took over for about a year or two during the War of 1812, when Bartlett retreated to his farm and orchard in New Gloucester. Elias took over from 1818 to 1821. Ira didn’t run the shop, but he did create some markers that are found today in local cemeteries.

Elias was no doubt quite familiar with his uncle’s stone shop and Eastern Cemetery when he returned to Portland from Massachusetts in 1817. He’d spent time in his teens working on stones in Portland while his older brother Alvan was in charge. During that time Elias carved his initials on the bottom of at least a half dozen slate markers being produced by his older brother Alvan. He was, perhaps, practicing his lettering on his brother’s supply of slate. With respect to finished stones, the brothers had unique lettering and designs so we can now easily sort markers and properly assign them to their carvers.

He arrived back in Portland very soon after his June marriage to 16-year-old Lydia Allen. At the time of their marriage he was 21 and Lydia was already pregnant with their first child, who she delivered in Portland five months later.

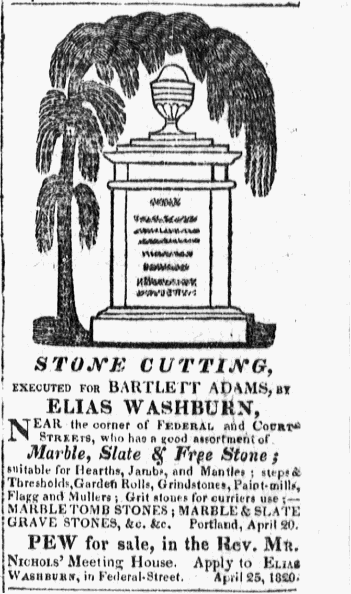

Bartlett and Elias entered into an agreement in October of 1817 that allowed Elias to run the shop while Bartlett went to Boston to help his brother open the shop there. Elias ran occasional ads in the newspaper during his time in Portland, but one from 1820 is shown here (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

- STONE CUTTING EXECUTED FOR BARTLETT ADAMS, BY ELIAS WASHBURN, Near the corner of FEDERAL and COURT STREETS, who has a good assortment of Marble, Slate & Free Stone; suitable for Hearths, Jambs, and Mantles; steps & Thresholds; Garden Rolls, Grindstones, Paint-mills; Flagg and Mullers; Grit stones for curriers use; —MARBLE TOMB STONES; MARBLE & SLATE GRAVE STONES, &c. &c. Portland, April 20.

PEW for sale, in the Rev. Mr. NICHOLS’ Meeting House. Apply to ELIAS WASHBURN, in Federal-Street. April 25, 1820.

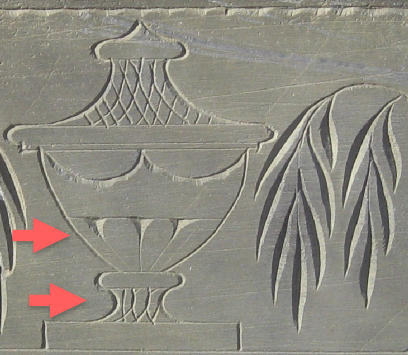

Most stonecutters of the period had a signature design, and Elias had one that I’ve found on about 100 gravestones in 30 Maine cemeteries. Elias’ signature design was an urn with a swag resembling a chain link.

Most often, he carved a weeping willow tree to the left of the urn featuring medium-length fronds that arc over the urn itself. The bottom of the urns of this design consisted of fluting of four or more lobes.

More often than not, Elias’ carvings were unrefined. Sloppy lines, uneven fluting, misspelled words, spacing issues and other problems with lettering and numbering all added up to his being a mediocre gravestone maker. His uncle Bartlett did amazingly precise and beautiful work; his brother Alvan was accomplished—somewhere in the middle of the two.

Elias did have some successful carvings. I’ve found a few of his signature urns that were precise, evenly carved, and error-free. But those are in the minority of the collection he left behind.

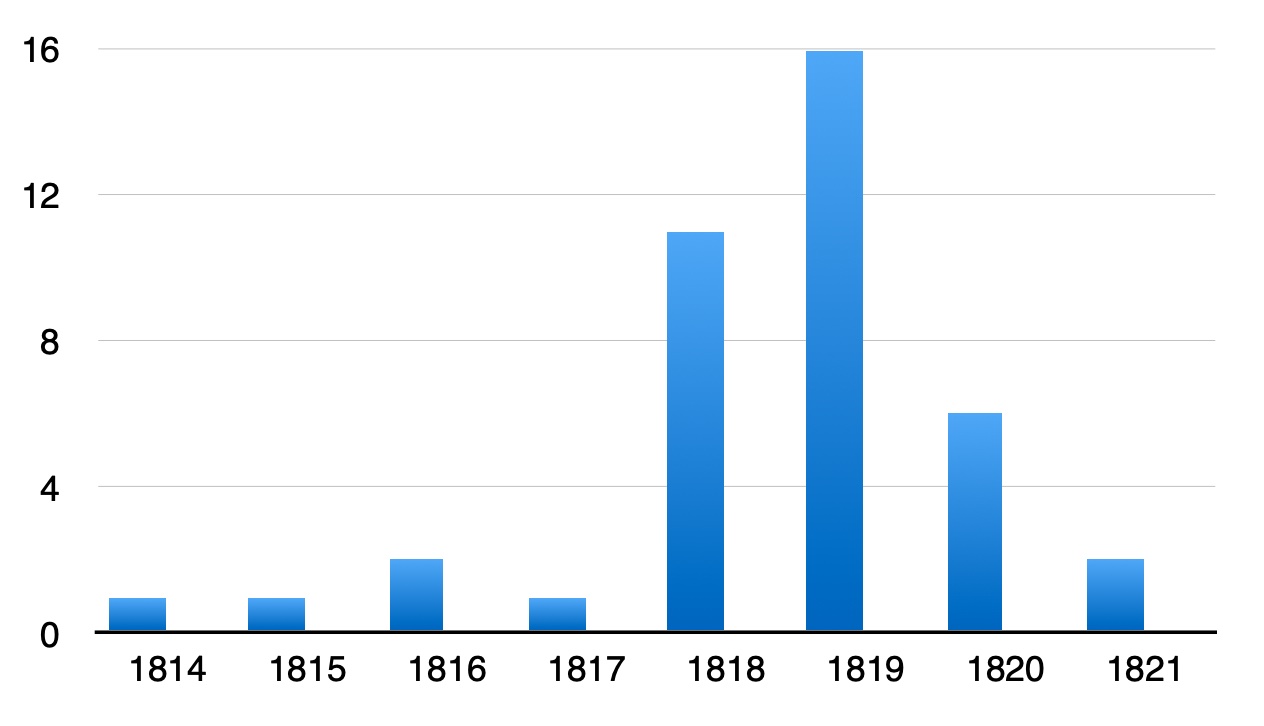

About 40 of his signature urns are found on markers at Eastern Cemetery. We can assume that the majority of gravestones from this period were made within a few months of the person’s death. Chart 3 shows the distribution of Elias’ signature urn design at Eastern Cemetery.

Chart 3: Elias Washburn’s signature urns at Eastern Cemetery

Figure 19.

- Chart of 8 bars labeled by year. 1814, 1815, 1816, 1817, 1821: under 4. 1820: between 4 and 8. 1818: between 8 and 12. 1819: 16.

Elias’s urns decorate the Eastern Cemetery stones of these six who died in 1820:

- George Hill, age 5, who died in February,

- Tamsin Thurlo, age 85, who died in March,

- Thomas Murdock Evans, age 5 months, who died in May,

- Elizabeth Clark, age 2, who died in June,

- Harriet Murch, age 7 months, (daughter of Josiah & Almira) who died in September, and

- Edward Hill, age 1, who died in November.

The marker for Harriet Murch is badly damaged, but included here to show Elias’s signature urn.

Figure 20.

This image (Figure 21) of Elias’s urn, also from Eastern Cemetery, better shows his lack of precision in carving. Note the fluting on the bottom of the urn. The four lobes are uneven in size and shape. Lines at the stem of the urn were also sloppily rendered.

Figure 21.

He generally did quite well with his tree fronds. The ones shown here are nicely carved.

Things didn’t end well between Elias and his uncle. Once Bartlett returned to Maine in 1821, he resumed his operations, but Elias apparently continued to charge expenses to Bartlett’s business. It led Bartlett to place a notice in the newspaper stating that since Elias had refused his request to end their business relationship, Bartlett was claiming the 1817 agreement to be null and void.

Elias left Portland, spent a short amount of time cutting stones in Eastport, Maine, (where a half dozen of his signature urn carvings are found), and eventually went back to Massachusetts. He and Lydia had four children in all. But his life was cut short in 1826, when he died at the age of 30, just six months after his namesake infant son died.

Stonecutter Abel Davis

While Elias Washburn was the resident stonecutter for Portland at the time of statehood, a second carver named Abel Davis worked in the shop and left his own collection of stones behind. Abel Davis, of Massachusetts, was born in 1798. His move to Portland was sometime in 1820 or early 1821. He paid poll taxes in Portland for 1821 and 1822.

He was talented and creative, often carving highly decorated surfaces with potted trees and elaborate borders such as this one from 1821 found at Eastern Cemetery (Figure 21).

Figure 22.

His numbering featured exaggerated loops on his 2s and 3s. The photo on the cover of this paper is from a stone carved by Abel Davis—note the looped numeral 2. I’ve attributed at least ten 1820-dated gravestones at Eastern Cemetery to Davis.

An interesting stone I’ve assigned to him is for Nancy Dennison, who died at age 12 in September of 1820 (Figure 23). Her inscription features Abel’s signature looped 2. But the design on this stone is quite special. It features what appears to be a stylized monstrance (Figure 24), suggesting that Nancy Dennison was Catholic. This design was used on three other markers at Eastern Cemetery for others known to have been Catholic.

Figure 23.

- NANCY M. dau’r of James & Sarah Dennison, died Sept. 14, 1820: AEt. 12.

Figure 24.

Abel Davis’s time in Portland was brief. By 1823 he was back in Massachusetts carving stones there.

A survey of stones for 1820 at Eastern Cemetery

Recall that I found 70 people confirmed to be at Eastern Cemetery based on burial records and or presence of a grave marker. About half of those have an individual gravestone that was carved for them in or soon after 1820. I have set aside the remaining ones for a variety of reasons:

- 12 buried in typical plots and named on shared family gravestones with multiple dates

- 9 buried in a tomb. Family monument may or may not be on site

- 5 at a grave where only a destroyed remnant of a marker remains

- 4 at a grave where a stone is present but highly eroded and illegible

- 2 with grave stones lost/missing

- 1 at a grave with only a slate footstone present

- 1 at a grave decorated with a modern-day granite veteran’s marker

There are 36 people who died in 1820 that have their own marker at Eastern Cemetery. The majority (30 of 36) are slate, and 6 are marble. Slate was the predominant stone of choice through about 1840, but the transition to marble was occurring as early as 1800 and took a couple of generations. So the gravestones being made in Portland at the time of statehood consisted of this mix of slate and marble. Slate far outlasts marble, which more easily erodes away over time, so it is likely that many more marble gravestones were created for these 1820 burials than we can account for today.

The carvers who created these gravestones were Bartlett Adams, Elias Washburn, Abel Davis, and perhaps one or two others who I’ve not yet figured out (carver sorting is always a work in progress).

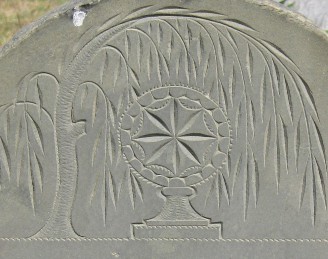

With respect to decoration, the stonecutters of the time were focused on urns & willows. A few stones in Eastern Cemetery’s 1820 collection were undecorated, but the rest—except for the monstrance on Nancy Dennison’s stone—had urns, with our without willows. A few close up examples from 1820 are shown (from top to bottom, they are Lucy Robinson (Figure 25), Phebe Sawyer (Figure 26), John Coit Smith—undecorated (Figure 27), and Robert Mitchell (Figure 28).

Figure 25.

Figure 26.

Figure 27.

Figure 28.

Wrapping up

I wrote this paper during the 2020 worldwide Covid-19 pandemic, a time in which we have instant access to information, advanced medical knowledge, and excellent medical care systems and facilities, things that were unavailable to the citizens of Portland in 1820. An epidemic at that time would not have been well-understood and people would have suffered blindly as the illness struck down their family and neighbors. But, fortunately, it seems no epidemic illness wreaked havoc on the townspeople the year of Maine’s statehood.

The list of 153 people whose deaths occurred in 1820 that I’ve been able to find is at the end of this paper, with notes as to burial location.

I shout out a “thank you!” to Tiffany Link at Maine Historical Society for helping me identify source documents and Martha Zimicki from Spirits Alive for supplying transcription forms…

Table of the 153 people found in death records for Portland in 1820

Note regarding ages: when age is 0, it means any child up to age 1

For details about “confirmed at EC” versus “presumed at EC,” read the section, Some Numbers for Eastern Cemetery

| Notes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams | Moses | 53 | confirmed at EC | Paper: “Seated by the fire, in the act of reaching for the tongs, fell forward and expired without a groan.” |

| Adams | William | 16 | confirmed at EC | |

| Alden | Franklin | 17 | confirmed at EC | Notable person, lost at sea |

| Anderson | Mary | 52 | presumed at EC | |

| Andrews | Jonathan | 50 | confirmed at EC | |

| Attwood | Infant child | 0 | presumed at EC | Infant child of Capt. Bradbury Attwood |

| Barnes | Cornelius | 16 | confirmed at EC | |

| Bartlett | Caleb | 64 | Stroudwater | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland |

| Bartlett | Mary (Small) | 35 | Stroudwater | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland |

| Bartlett | Richard | 35 | presumed at EC | Death by drowning |

| Berry | Joseph | 33 | presumed at EC | |

| Berry | Lydia | 40 | presumed at EC | Died at the Alms-House |

| Bishop | Mrs. Catharine | 75 | Fobes Cemetery | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland (also called Maplewood Cemetery) |

| Boaz | Mrs. Hager | 51 | presumed at EC | African-American |

| Bradford | Harriet (Churchill) | 34 | confirmed at EC | |

| Bryant | James | 64 | out of town | Newspaper stated Lisbon, Me. |

| Burnham | Amos | 30 | presumed at EC | |

| Byrne | Michael | 23 | at sea | |

| Cammett | Paul | 66 | presumed at EC | |

| Carnighan | Betsey | 50 | confirmed at EC | |

| Chase | Ellen | 0 | confirmed at EC | |

| Chase | Samuel Y. | 21 | confirmed at EC | |

| Clark | Elizabeth | 2 | confirmed at EC | |

| Coolidge | Jonas | 21 | confirmed at EC | Transcription project notes: only a slate footstone present, with intitials J.C. |

| Corry | Charles Francis | 1 | confirmed at EC | |

| Corry | Francis | 21 | confirmed at EC | |

| Corry | Josiah | 19 | confirmed at EC | Died at Norfolk, VA; Named on his mother Esther’s marker, carved by Bartlett Adams. |

| Crockett | Child of Joseph | 0 | presumed at EC | |

| Cushing | Loring | 67 | confirmed at EC | Revolutionary War veteran |

| Cushman | Capt. Charles | 25 | outside USA | Newspaper stated St. Jago de Cuba |

| Cutler | Mrs. Mary | 82 | presumed at EC | |

| Damrel | Edward | 23 | out of state | Newspaper stated Staten Island, NY, en route home from Havana. |

| Dana | Elizabeth | 4 | confirmed at EC | |

| Dela | Daughter | 2 | presumed at EC | Daughter of Fobes |

| Johnson | Eleanor (Lamb) | 79 | Stroudwater | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland |

| Joice | Sarah Jane | 2 | confirmed at EC | |

| Jordan | Cpl. James | 67 | confirmed at EC | Revolutionary War veteran |

| Jordon (Jordan) | Stillman | outside USA | Newspaper stated Havana | |

| Knight | Amelia | 0 | confirmed at EC | |

| Knight | Miss Elizabeth | 26 | Knight-Sawyer | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland (assumed burial location) |

| Knight | Samuel (Jr.) | 65 | Knight-Sawyer | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland |

| Knox | Ebenezer | 36 | outside USA | Newspaper stated St. Thomas |

| Libby | Samuel | 22 | confirmed at EC | Carver error “LIBBY” showing as “LBBBY” |

| Lloyd | William | 22 | presumed at EC | African-American, death by drowning |

| Loring | Jane | 1 | confirmed at EC | |

| Loring | Nicholas | 17 - 19 | at sea | |

| Mackie | Mrs. Joann | 21 | presumed at EC | |

| Mayo | Catharine | 44 | confirmed at EC | Nathan Hale collection (1978) lists her at tomb H - 71 as third wife of Ebenezer Mayo, Esq. |

| McCreary | Mrs. Elizabeth | presumed at EC | ||

| McLellan | Capt. Joseph C. | 88 | presumed at EC | Oldest living person in Portland at the time of his death. |

| Mead | Albert H. | 17 | at sea | |

| Megquier | James Holden | 37 | confirmed at EC | Some records use Megguire. He was possibly buried in New Gloucester |

| Merrill | Child of Enos | 1 | presumed at EC | |

| Mitchell | Mrs. Rebecca | 70’s | confirmed at EC | Stone: Died at Grand Manan, New Brunswick. |

| Mitchell | Robert | 69 | confirmed at EC | |

| Munroe | Lucy-Ann | 7 | presumed at EC | Death by burning |

| Munroe | Tilley Merrick | 44 | out of state | Newspaper stated Norfolk, Va |

| Murch | Harriet | 0 | confirmed at EC | |

| Murdock | Alice Amelia | 23 | confirmed at EC | |

| Neal | James | 49 | presumed at EC | |

| Noyes | Jacob | 52 | confirmed at EC | Bartlett Adams urn & willow carving |

| Osgood | Thomas | 9 | presumed at EC | Death by drowning |

| Owen | Abigail | 54 | confirmed at EC | |

| Plummer | Mary | 24 | presumed at EC | |

| Poole (Pool) | Lieut. Abijah | 81 | confirmed at EC | Revolutionary War veteran |

| Pratt | Sherubiah | 76 | presumed at EC | |

| Pratt | William | 0 | confirmed at EC | |

| Radford | Benjamin | 73 | confirmed at EC | Revolutionary War veteran |

| Richardson | Ann H. | 1 | confirmed at EC | |

| Roach | Capt. Thomas L. | 55 | confirmed at EC | |

| Robinson | Capt. Joshua | 63 | confirmed at EC | New granite stone for Revolutionary War veteran |

| Robinson | Lucy Nichols | 0 | confirmed at EC | |

| Robinson | William | 54 | confirmed at EC | |

| Ryan | Charles | 31 | presumed at EC | |

| Sawyer | Eunice | 19 | Knight-Sawyer | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland |

| Sawyer | Infant child | 0 | presumed at EC | Infant child of Capt. Lemuel |

| Sawyer | Phebe Newman | 0 | confirmed at EC | |

| Seal | Ann | 16 | Pine Grove Cem | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland (and today part of Evergreen Cemetery) |

| Seavey | Child of David | 0 | presumed at EC | |

| Seavy | Child of William | 0 | presumed at EC | |

| Shattuck | Samuel | 32 | presumed at EC | |

| Shaw | Neal | 54 | presumed at EC | |

| Shaw | William March | 0 | confirmed at EC | |

| Simonton | Thomas D. | 19 | confirmed at EC | Bartlett Adams carving |

| Skilton | Mrs. Mary | 82 | presumed at EC | Died at the Alms-House |

| Smith | Arixene | 27 | confirmed at EC | |

| Smith | Edwin A. | 0 | Pine Grove Cem | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland (and today part of Evergreen Cemetery) |

| Smith | John Coit | 1 | confirmed at EC | |

| Smith | Mrs. Hannah | 37 | presumed at EC | |

| Stanwood | Capt. Winthrop | 26 | confirmed at EC | |

| Starbird | Mrs. Mary Ann | 20 | presumed at EC | |

| Stetson | Robert | outside USA | Newspaper stated Havana | |

| Stevens | Isaac Sawyer | 72 | Bailey Cem. | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland |

| Sweetser | David | at sea | ||

| Thaxter | Louisa | 2 | confirmed at EC | |

| Thomes | Phebe (Fickett) | 42 | Stroudwater | In 1820 part of Westbrook, but now Portland |

| Thurlo | Miss Tamsin | 85 | confirmed at EC | |

| Tucker | Sally (Miss) | 35 | presumed at EC | |

| Tucker | Sally (Mrs.) | 58 | presumed at EC | Newspaper: “She outlived her husband and ten children.” |

| Vaughan | Miss Elizabeth J. | 45 | Western Cem. | At the time, this was simply the Vaughan family’s private burial patch on their own land. |

| Waite | Col. John | 88 | confirmed at EC | Revolutionary War veteran, Newspaper: “For many years High Sheriff of this county.” |

| Washburn | Ira | 6 | confirmed at EC | |

| Waterhouse | William | 55 | confirmed at EC | News: “He was an honest man, a kind husband, a tender parent and a benevolent friend.” |

| Webb | Jennett N. | 21 - 22 | confirmed at EC | |

| Webb | Sally | 36 | presumed at EC | |

| Webster | Thomas B. | 60’s | confirmed at EC | Revolutionary War veteran |

| Webster | Thomas Edward | 0 | confirmed at EC | |

| Wiggins | Jane | 56 | presumed at EC | |

| Wilson | Joseph | 51 | confirmed at EC | |

| Wilson | William | outside USA | Newspaper stated Havana | |

| Wood (Woods) | Mary Ingelbert | 5 | presumed at EC | |

| Woodman | Paulina (Libby) | 23 | presumed at EC | |

| York | Emeline J. | 0 | confirmed at EC |

Sources

Description and PDF version: Mortality and Memorialization in Portland at the Time of Statehood

Published Sources

- Jordan, William B. Jr., Burial Records ... of the Eastern Cemetery. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 2009.

- —— Burial Records ... of the Western Cemetery. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 2011.

- —— Record of Interments with Historical Notes. 1978 manuscript.

- Master Plan for Eastern Cemetery, Portland, Maine. Chicora Foundation, Inc. 2011.

- McLellan, Hugh D. History of Gorham, ME. Portland, ME: Smith & Sale Printers, 1903.

Other Sources

- Ancestry (vital records, census files, family trees...)

- Find a Grave (gravestones, cemeteries)

- Genealogy Bank (Weekly Eastern Argus, Gazette, and other newspapers from 1820)

- Maine Historical Society collections (vital records, historic newspapers)

- Spirits Alive transcription project forms