Dr. John Perkins Briggs (1791–1837): A Surgeon in the War of 1812

Ninth in a series of Occasional Papers about Eastern Cemetery in Portland, Maine

by Ron Romano

© November 2020

Image of Dr. Briggs courtesy of Steve Strout, from his family collection

Early in 2020, Tammy Mansfield, President of the Alexander Slidell MacKenzie chapter of the US Daughters of 1812, contacted Spirits Alive, the nonprofit friends of Eastern Cemetery group in Portland, Maine. She was writing from her home in Wyoming, and said that her organization was hoping we would help them place a veteran’s medallion at the grave of Dr. John Perkins Briggs, a veteran of the War of 1812 who died in 1837.

Thus began a conversation that lasted over the summer and into the fall. Here in Maine, we secured approval from the City of Portland to have the medallion placed on Briggs’ grave. Back in Wyoming, Tammy obtained the medallion and made arrangements to ship it east. Along the way I met Steve Strout, a direct descendent of Dr. Briggs, who generously shared his knowledge of his ancestors. Though we had hoped to honor Dr. Briggs in the fall of 2020, the pandemic stalled those plans. In the spring of 2021, the medallion shown below will be placed on Dr. Briggs’ grave at Eastern Cemetery during a ceremony hosted by Spirits Alive.

This paper tells the story of Dr. Briggs and his service to our country some two centuries ago...

Contents

- Off to War

- A Family Treasure

- Back to Maine and growing the family

- Two sons named William

- The 4th US census, recorded 1820

- The 5th US census, recorded 1830

- The 6th US census, recorded 1840

- The death of Dr. Briggs

- A legacy beyond his military service and large family

- The attraction of La Salle, Illinois

- Dorothea “Dolly” Fifield (Boynton) Briggs Pease

- Final resting places

- Appendix: Another interesting discovery during research

- Final words...

- References

John Perkins Briggs was born September 4, 1791, in Gorham, Maine, the first child of Abiel and Polly (Dunn) Briggs. His middle name was surely given to honor the memory of Abiel’s first wife, Lucy Perkins. She wed Abiel Briggs in 1786 but died within two years of their marriage. Abiel’s marriage to Polly occurred in January 1791.

In his late teens, John married Dorothea Fifield Boynton in Cornish, Maine. Dorothea (often referred to as “Dolly,” sometimes “Dora,” and in her own handwriting “Dorothy”) was the same age as John, having been born in Stratham, New Hampshire, in July 1791 to Samuel and Mary (Deering) Boynton.

The young couple spent their first few years together living with Dolly’s parents in Cornish. In the third US census taken in 1810, we find her father Samuel Boynton as the head of a large household of 12, including a male and female in the age band of 16 to 25.1 John and Dolly were 19 that year. They began a family of their own right away, but they had started their lives together during a very challenging time. Maine’s (indeed the nation’s) economy was in shambles due to the unexpected effects of President Jefferson’s 1807 Embargo Act, which had shut down international trade. Further, tensions were high with England over their continuing practice of impressing US sailors into service for their naval fleet. These challenges reached a peak towards the end of James Madison’s first term as president; he declared war with Great Britain in June of 1812 and so began the War of 1812.

Off to War

John P. Briggs, just 21, joined the war effort within a year. According to historian Larry Glatz of Scarborough, Maine:

On April 6, 1813, Briggs applied for an appointment as surgeon’s mate in the newly formed 33rd United States Infantry, headquartered in Saco. His commission was approved just four days later. Briggs' initial assignment was most likely the examination of recruits, large numbers of which were enlisted in the spring and summer of 1813. He was on duty at Fort Scammel in Portland Harbor by September, 1813; and he was subsequently transferred with his regiment to the northern front. Whether he was with the troops in the regiment's first important battle—at Chateauguay, Quebec, on 26 October 1813—is not known; but by May, 1814, he was serving on Lieutenant Thomas Macdonough’s Champlain flotilla.

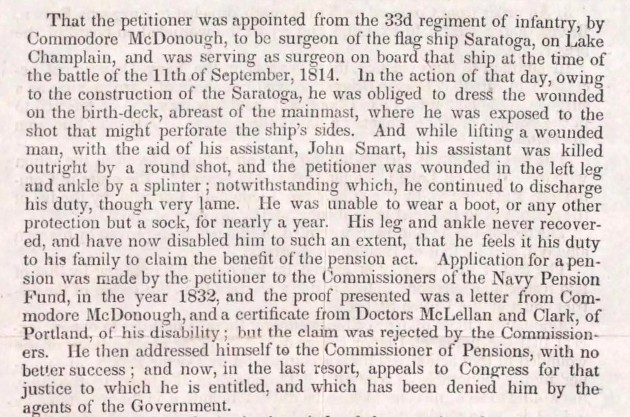

Though Briggs began his service in 1813 as a surgeon’s mate, he was by the following year being referred to as “Dr. Briggs.” In 1814, he was injured during the September 11th Battle of Lake Champlain (or the Battle of Plattsburgh). The US had established a war pensions program for veterans soon after the American Revolution, but much of the program was repealed before the War of 1812. With respect to Dr. Briggs, it appears his first application for benefits wasn’t filed until around 1832. He was initially denied benefits, but then filed an appeal which reached the US Congress in 1837. The following (Figure 1) is copied from the report to Congress that year; it provides details of the battle and his injury many years earlier.2

Figure 1.

- That the petitioner was appointed from the 33d regiment of infantry, by Commodore McDonough, to be surgeon of the flag ship Saratoga, on Lake Champlain, and was serving as surgeon on board that ship at the time of the battle of the 11th of September, 1814. In action of that day, owing to the construction of the Saratoga, he was obliged to dress the wounded on the birth-deck, abreast of the mainmast, where he was exposed to the shot that might perforate the ship’s sides. And while lifting a wounded man, with the aid of his assistant, John Smart, his assistant was killed outright by a round shot, and the petitioner was wounded in the left leg and ankle by a splinter; notwithstanding which, he continued to discharge his duty, though very lame. He was unable to wear a boot, or any other protection but a sock, for nearly a year. His leg and ankle never recovered and have now disabled him to such an extent, that he feels it is his duty to his family to claim the benefit of the pension act. Application for a pension was made by the petitioner to the Commissioners of the Navy Pension Fund, in the year 1832, and the proof presented was a letter from Commodore McDonough, and a certificate from Doctors McLellan and Clark, of Portland, of his disability; but the claim was rejected by the Commission of Pensions, with no better success; and now, in the last resort, appeals to Congress for that justice to which he is entitled, and which has been denied him by the agents of the Government.

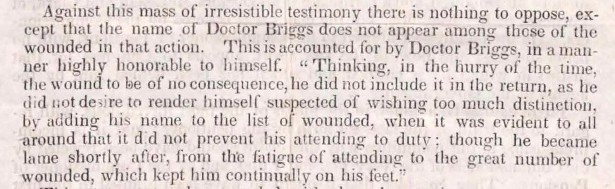

Briggs’ initial petition was not granted in 1832 because he had failed to include his own name on the list of those injured during the battle. In this second piece from the 1837 appeal to Congress, the reason for this omission is explained (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

- Against the mass of irresistible testimony there is nothing to oppose, except that the name of Doctor Briggs does not appear among those of the wounded in that action. This is accounted for by Doctor Briggs, in a manner highly honorable to himself. “Thinking, in the hurry of the time, the wound to be of no consequence, he did not include it in the return, as he did not desire to render himself suspected of wishing too much distinction, by adding his name to the list of wounded, when it was evident to all around that it did not prevent his attending to duty; though he became lame shortly after, from the fatigue of attending to the great number of wounded, which kept him continually on his feet.”

Dr. Briggs was awarded a pension of $25 per month on appeal, but he did not live more than a few months afterwards. His wife, Dolly, then had to petition the government to continue to receive the pension after his death.

According to Larry Glatz, soon after the 1814 battle, Dr. Briggs was awarded $1,162 in prize money for his service on the Saratoga. Despite the loss of lives and injuries suffered by so many, the Americans had been victorious that day and their success on Lake Champlain had halted the British invasion from the north.

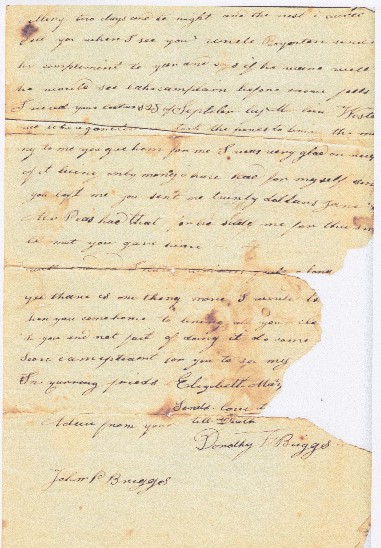

A Family Treasure

Within days of this victory, Dr. Briggs sent a letter home to his wife to let her know that he had survived. Her reply, a letter written from Cornish on October 13, 1814, has survived for over 200 years in the Strout family’s collection. It consists of four pages (two sheets written on both sides), signed “Dorothy F. Briggs” and addressed to “Doc’t John P. Briggs, Surgeon—Ship Saratoga, Lake Champlain.” The last page is shown (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dorothy wrote that she was “delighted on receiving such a proof of your conduct...” referring to his heroic actions aboard the Saratoga during the battle. She told him that she was surprised to learn what a “short space there was between you and eternity,” and hoped that he would not forget the goodness of God for sparing his life.

Still, she was clearly worried and wanted him home, writing that her health was “not very good” but that if she could only see him she would feel well again.

She wrote that by the time the lake would freeze, “I hope you will think of the unhappiness of your wife and get discharge and come home.” She made no mention of his injury...perhaps he had decided to keep that from her to prevent further worry. Of their young children she wrote, “your little children are well and talks (sic) much about you and says when will Pa come home...”

Towards the end of the letter she mentioned that she had received the $20 from “Mr. Peas” that John had sent home to her. That was Simeon Pease, who would help Dorothy and her kids settle John’s affairs after his death.

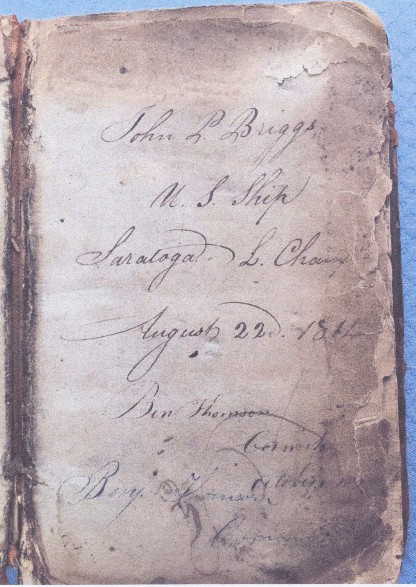

Figure 4 is the inside cover page of the medical reference book that Dr. Briggs used during the war. Note the date of August 22, 1814, which was just a month before the storied battle. Published 1809 by Robert Hooper and entitled “The Anatomist’s Vade-Mecum, Containing the Anatomy and Physiology of the Human Body,” this book was sold at auction online. The image was taken from the online auction record.

Figure 4.

The auction listing noted “Briggs would have had his hands full as there were heavy casualties, including himself, as the Saratoga, flagship of the line, took on HMS Linnett and HMS Confiance. The initial broadside took out half of Saratoga's guns and flattened half the crew. A brilliant maneuver allowed Saratoga to come about and bring the guns on the undamaged side of the ship to bear on the enemy.”

Among the papers in Dr. Briggs pension file is another note that helps bring us back to the chaos of the battle scene. Joseph Morrison, a lieutenant aboard the Saratoga during the battle, wrote a letter in support of Dr. Brigg’s pension application. It reads in part, “I further testify that the ship Saratoga had no cock pit (and) that the Surgeon was as much exposed to cannon shot as any man on the birth-deck.”

Back to Maine and growing the family

After the war, Dr. Briggs returned to Maine. He and Dolly continued to build their family, though records related to their children are not complete. Much of the family history—rich with photographs, documents, and memories passed orally from one generation to the next—comes from Steve Strout, a direct-line descendent. That history, along with public records, leads us to a family tree consisting of at least 10 children: two boys who died young, and two boys and six girls who reached adulthood. There likely were other children whose details have become lost over the past 200 years.

Beyond census records we use vital, church & town records; deeds; newspaper notices of birth, marriage, & death; gravestone inscriptions & cemetery listings; and published genealogies to help us build family trees. Generally, records for males are more plentiful than for females. But in the case of the Briggs, the opposite proves true and we are left with more questions about their sons than their daughters. Records of birth dates for the children are particularly challenging, leaving us only with date ranges for the majority. So while we are quite confident in the “who” it’s the “when” that leaves this family tree less than 100% certain. What follows is the list of 10 children proven to be John and Dolly’s.

Dolly’s letter of October 1814 mentioned a son and daughter. They were:

Mary E. (Briggs) Cole, born 1810 to 1813, died 1887

Believed to be the first born. We have a good paper trail for Mary, as she is accounted for in census records spanning seven decades. While still in her teens she married Clark C. Cole in Limington, Maine in 1827. They had at least two children and lived in Cornish all of their lives. Clark was a farmer, carpenter and cabinet maker over the years. Both died at the age of 75, he in 1880 and she in 1887. Shown (Figure 5) is a shared grave marker for them at Riverside Cemetery in Cornish.

Figure 5.

John P. Briggs, born 1811 to 1813, died after 1854

Fewer records are found for first son, John P., named for his father and very likely with the same middle name of Perkins. According to family history, he worked in medicine as had his father and brother, yet no records are found to support that. Instead, there are clues that suggest he was a mariner and that he may even have been lost at sea. No confirming vital records of death or burial are found. We can account for him in the 1820 census for Cornish, Maine, but then lose track until 1844, when he was named on a deed selling (to his brother-in-law Benjamin DeMerritt) his 1/8 share of property he’d inherited upon his father’s death. Just below his name on the deed is that of Harriet E. Briggs, who was likely his wife, though again vital records of marriage are lacking. Further, although he was listed on that deed as being “of Portland,” neither he nor Harriet appear in the Portland directories published that decade. We lose track of him again until another deed in 1854, when he was named along with his seven siblings regarding another property transaction in Portland for which he was a 1/8 share owner. Interestingly, all of the others were named with their current towns of residence, but John had no residence listed—perhaps, again, supporting the notion of a life spent at sea.

Jane H. (Briggs) DeMerritt, born 1814 to 1815, died 1874

Born in Cornish 1814 or 1815, she may have arrived while her father was at war. She is found in census records from 1820 through 1870. In July 1837, she married Benjamin Franklin DeMerritt, who was a boot maker in Portland. Just three weeks after her marriage, her father died. Jane and Benjamin had at least six children. They moved about 100 miles southwest of Chicago to La Salle, Illinois, in 1851, where Benjamin established a business manufacturing shoes. Jane died in 1874 at age 60 in La Salle and was buried at the Oakwood Cemetery there. Benjamin remarried two years later.

Rebecca Harmon (Briggs) Stuart, born 1818 to 1821, died 1898

Like her older siblings, Rebecca was born in Cornish. In August of 1837—just a month after her sister Jane’s marriage—she married William Franklin Stuart, a native of New Hampshire. They lived in Maine where William worked as a cooper. They had at least six children. In another parallel to her sister Jane, Rebecca and her family moved to La Salle, Illinois (after 1851 but before 1857). Her husband predeceased her in 1889. According to family records Rebecca died in La Salle in 1898 at age 77, but her place of burial is not known.

While most records refer to her as “Rebecca” it is worth noting that in October 1851, she joined two sisters, Mary and Charlotte, in writing a letter that affirmed the legitimacy of Simeon Pease as the executor of their father’s estate. She signed her name “Rebecah.”

Hannah Barker (Briggs) Strout, born 1822 to 1825, died 1890

Hannah was born in Cornish. Her gravestone gives her birth as January 1825, while the 1850 census notes her age as 28 (and therefore a birth year of 1822). That earlier date is more likely, since we have a vital record of her marriage in 1838 to David Porter Strout of Cape Elizabeth, Maine, and record of the arrival of their first child in 1839. In either case, she was very young at the time of marriage—between the ages of 13 and 16.

The image (Figure 6) (courtesy of Steve Strout, Hannah’s 3rd-great-grandson) is from a daguerrotype of Hannah in the 1840s or 1850s. She appears to be holding a child that has died.

Figure 6.

I sent the image to post-mortem photography expert Libby Bischof. She noted “almost definitely this is a post-mortem photograph. The woman is certainly in mourning clothing, and the photographic best practices of the time advised photographers to make it look as if the deceased child was sleeping.”

Though family records for Hannah do not include the names of any children who died in infancy in the 1850s, there was a long span of time between her children born in 1842 and 1856. It is entirely likely that this child was born and died within that 13-year period, but because of the early death went unrecorded in the family papers

Hannah and David Strout first lived in Cape Elizabeth, but by 1842 they had relocated to La Salle, the first among John & Dolly Briggs’ kids to do so. David Strout was a farmer. He died in 1859 and Hannah remarried ten years later to Jonathan Edmonds. She died in 1890 and was buried at Rockwell Cemetery, where her first husband David was also laid to rest.

Two sons named William

There was a common practice in the 1700s and 1800s (when infant mortality was very high) for families to give a new child the same name as had been given to an older sibling who predeceased him or her. I know of one specific case involving another family at Portland’s Eastern Cemetery which had three sons of the same name in succession, each born soon after the death of his brother.3 But what I do not recall seeing is a family with two living sons of the same first name. It appears that John and Dolly Briggs did just that—had two sons who they named William.

William David Briggs, born 1821 to 1826, died 1865

A robust paper trail exists for William David Briggs, which confirms his being part of this family. He, like his father, was a medical man and he served as an assistant surgeon briefly during the Civil War. He appears in deeds in Portland in 1847 and 1854. The 1854 deed discussed above under John’s profile is the most compelling, as it names him along with seven siblings each of whom became a 1/8 owner of property owned by their mother and step-father. On that deed, William was listed as living in New York City.

A challenge with respect to William David Briggs is his year of birth. Three sources are found, each of which is generally considered to be reliable. First is his Civil War military pension file, which gives his age in 1865 as 44, and therefore a birth year of 1821. An 1865 newspaper notice of death says he died at age 40 (birth year would be 1825). The 1860 census for La Salle, Illinois, gives his age of 34 (birth year would be 1826).

In the 1860 census he is named as a physician born in Maine. His household included his wife Ellen (she was Ellen Maria Ballou, who he married in La Salle in 1857), 2-year-old daughter Ella (she would be their only child), and his mother Dolly (then a widow for the second time and named as Dora Pease).

His service during the war was brief. He was sent to the south early in 1865 and suffered great fatigue and exhaustion, becoming quite ill. He was never able to recover and was still ill when discharged from service in July 1865. He soon developed tuberculosis (referred to then as consumption), and it was of that disease that he died at home in La Salle in November 1865. A veteran’s gravestone is found for him at Rockwell Cemetery in La Salle. It reads:

W. D. Briggs

Asst. Surg’n

11th Ill. Inf.

His military file includes documents related to his widow, Ellen’s, right to a continuing pension given that William’s death was determined to have been related to his exposure to the elements while on duty. She received a pension benefit of $17 per month through her death in 1900. She never remarried.

William P. Preble Briggs, born 1827, died 1832

There is much less of a paper trail for 5-year-old William P. Preble Briggs than for his brother. He has a broken and eroded marble grave marker at Eastern Cemetery in Portland at Plot G-148, adjacent to the shared gravestone for his father and brother Henry. The remnant of William’s gravestone is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

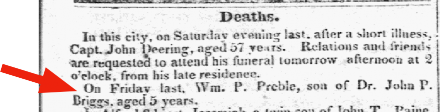

His burial record noted his parents as “John P. & Dora F. Briggs.” We also find a newspaper death notice that is compelling proof of his placement within this family. Below (Figure 8) is the notice published December 10, 1832 in the Portland Eastern Argus newspaper. Being age 5 in 1832, his year of birth would have been about 1827.

Figure 8.

He was no doubt named for Willam Pitt Preble, who was one of the first justices appointed to the Maine Supreme Court in 1820 when Maine separated from Massachusetts to become a state. Preble served as a justice until 1828, when he stepped down from the bench in order to take charge of Maine’s northern border with New Brunswick, Canada. In William’s father’s military records, we find a letter written by William Pitt Preble in August of 1837, just a month after the doctor’s death, advocating for Dolly Briggs’ entitlement to the doctor’s pension. Preble had also witnessed an 1837 deed for the family.

What can we make of these two boys named William? Records support that they both were sons of Dr. John and Dolly Briggs. The most likely explanation comes from Tammy Mansfield. She suggests that the boys were twins, and that their parents gave them the same first name but different middle names. Supporting this is the 1830 census which included two males in the household under age 5. Although William David’s birth year spans five years in the records, the latest is 1826. The only record for William Pitt Preble is the newspaper notice of death. What if there had been a simple transcription error in the newspaper and his age was 6 instead of 5? That would get us to the same year of birth (1826) and would give credence to Tammy’s theory. I can imagine that while Dolly was pregnant, she and John had decided that if they had a boy, they’d name him for William Pitt Preble, the well-respected justice and a man known by the family. When twin boys were born instead of one, they decided to name them both William but gave differing middle names.

There may be another explanation. In any event, until the truth is fully uncovered we have two sons named William born at or about the same time, one of whom died young and the other who lived to serve his country in the Civil War.

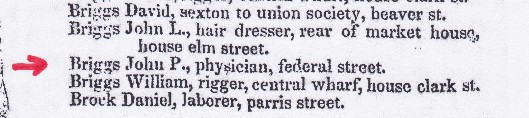

The seven children profiled thus far were born in Cornish; the 1820 and 1830 censuses confirm this. Dr. Briggs moved his family to Portland in the fall of 1830, as he was found in the 1831 Portland Directory as follows (Figure 9):4

Figure 9.

The following children were born in Portland. None would have had much opportunity to know their father since he died while they were all quite young. Instead, the girls grew up in the household of their stepfather, Simeon Pease, and the boy died in infancy, soon after his father.

Eliza (Briggs) Darrow, born 1832, died 1911

Eliza lived first in Portland, then at age 5 moved to Cornish until her late teens. She left Maine for La Salle, Illinois, in late 1850 or early 1851, and married there in June of 1851. Her husband was Sidney Darrow, an insurance man for a while, who was ten years older than she. They had at least nine children, and while Eliza passed away as a widow in 1911 in Chicago, she was buried at Oakwood Cemetery in La Salle. There is a good paper trail for Eliza, and we can account for her in five census records.

Charlotte (Briggs) Carr, born 1833, died 1857

Charlotte also went from Portland to Cornish, and then in her late teens to La Salle with her siblings. Charlotte married Henry Carr in La Salle when she was 20 (in 1853). She died in childbirth four years later, and was buried at Rockwell Cemetery in La Salle. Given that she lived only 24 years, we can account for her only in two censuses.

Henry H. Briggs, born 1836, died 1838

Though no vital records are found for Henry, he was memorialized on his father’s gravestone at Portland’s Eastern Cemetery with an inscription which reads that he died May 16, 1838 at age 20 months (Figure 10). The words just below his name are “Son of Dr. John and Dora F. Briggs.”

Figure 10.

So, Dr. Briggs spent his final years in Portland. The directory for 1834 reads the same as for 1831 (Figure 9). Then, in his final entry in the city’s directories (1837) he was at a new address on Oxford Street near Elm Street.

When we look at the list of children he and Dolly brought into the world there are—as noted above—questions related to exact years of birth for some. But within the extraordinary number of years that Dolly was bearing and raising children there are some multi-year gaps that suggest there could have been other children born but who did not survive infancy and therefore were not accounted for in available records.

One good way to examine this is to review census records and look for unknown individuals after accounting for the known children. Even this is not exact, since children were not named on census records until 1850, so we must work within age and sex bands provided for each census. Below we take a closer look at the census records for 1820, 1830, and 1840 in order to look for children beyond the 10 we already know.

The 4th US census, recorded 1820

Below (Figure 11) is the line from the 1820 US census for Cornish, showing John P. Briggs and giving the household breakdown.

Figure 11.

- 2 males under age 10 (One of these is John, but there was apparently another son born between 1811 and 1820)

- 1 adult male age 26–44 (the doctor)

- 2 females under age 10 (Jane and Rebecca)

- 1 female age 1015 (Mary), and

- 1 female age 10–15 (Mary), and

- 1 adult female age 26–44 (Dolly).

The 5th US census, recorded 1830

There were nine people in Dr. Briggs’ family recorded living in Cornish that year. Mary was already married and living elsewhere with her husband, and John had also already left home (perhaps at sea?)

- age 30–39, 1 male & 1 female (These were the doctor and Dolly, both age 39)

- age 15–19, 1 female (Jane)

- age 10–14, 1 male & 1 female (Rebecca and the second male we found in the 1820 census. Now we can narrow down his year of birth as being between 1816 and 1820)

- age 5–9, 1 female (Hannah)

- under age 5, 1 female & 2 males (the two males are William and William—as twins? The female is unknown, born between 1826 and 1830)

The 6th US census, recorded 1840

By 1840, Dr. Briggs had died and Dolly had remarried, so these details are from the household of Simeon Pease of Cornish.

- age 50-59, 1 male (Simeon Pease)

- age 40–49, 1 female (Dolly)

- age 20–29, 1 male & 1 female (This could be John & Harriet? or perhaps Simeon’s children)

- age 15–19, 2 females (Hannah and Rebecca—if born 1821)

- age 10–14, 1 male (William D.; his brother William P. P. died in 1832)

- age 5–9, 2 females (Eliza and Charlotte)

- age 5–9, 1 male (Here is a new entry. This is a child born 1831 to 1835 who is not known. This child could very well have been a grandchild or step-grandchild of Dolly and not her own child.)

The result of this exercise tells us that in addition to the 10 known children, Dolly and the doctor probably had at least two more. If this is accurate, they would be:

- A son born 1816 to 1820. If true, he must have died before 1854 since he does not appear on the deed that names the eight surviving siblings.

- A daughter born 1826 to 1830. If true, she must have died before the 1840 census.

Family lore is that the Briggs had 12 children in all, and random notes in family records suggest the possibility of a son being named Franklin or Sylvester. Another interesting note in the family records suggests there was a daughter, Dorothea, named for her mother. The note reads, “Dorothea, drowned in well age 14.” If Dorothea was the daughter born between 1826 and 1830, her accidental death could have occurred just before the 1840 census.

The death of Dr. Briggs

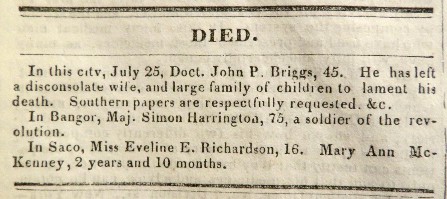

In the summer of 1837, at age 45, Dr. John Perkins Briggs died in Portland of unknown causes. Figure 12 is his death notice in the Daily Eastern Argus on August 4, 1837. His death was covered in two other newspapers, though they just gave his name and age.

Figure 12.

- DIED. In this city, July 25, Doct. John P. Briggs, 45. He has left a disconsolate wife, and large family of children to lament his death. Southern papers are respectfully requested, &c. In Bangor, Maj. Simon Harrington, 75, a soldier of the revolution. In Saco, Miss Eveline E. Richardson, 16. Mary Ann McKenney, 2 years and 10 months.

The burial record that was created for him (as published in Bill Jordan’s 2009 “Burial Records...of the Eastern Cemetery...”) incorrectly gave his year of death as 1838. Many vital records in Portland were created from gravestone inscriptions, and this may be true for Dr. Briggs, as his gravestone was also erroneously inscribed with the year 1838 and the age 46.

Dr. Brigg’s white marble gravestone is found in Eastern Cemetery at plot G-147. Though eroded and somewhat covered with lichen at the time this photo (Figure 13) was taken (summer 2020), it is still intact. The inscription just below his name makes reference to his military service; we can just make out the date of September 11, 1814, though the years of weathering have made the other words on the inscription a challenge to read.

Figure 13.

A legacy beyond his military service and large family

An interesting sidebar to the Briggs story is found in some newspaper advertisements published well after his death. Dr. Briggs had apparently developed an elixir that proved popular in the treatment of stomach and bowel disorders. Over four months in 1840, Charles B. Smith ran the ad (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

- BRIGGS’ BITTERS These Bitters, originally prepared by the late Doct. JOHN P. BRIGGS, or Portland, are decidedly one of the best preparations of the kind which has been offered to the public. They are a warm cordial stomachic; slightly cathartic, and are peculiarly fitted to remove from the stomach and bowels any accumulation of billious matter and to give a vigorous and healthy tone to the organs of digestion. They are now prepared and put up from the original recipe of Dr. Briggs. in his own handwriting, and for sale wholesale and retail by CHARLES B. SMITH, West Market Row, Congress St. Portland. March 21. 8wd&w

Then in 1841, the Kennebec Journal newspaper (published in Augusta) ran a similar advertisement, but this series included patient testimonials (Figure 15). Note that jaundice had been added to the list of conditions that Briggs’ Bitters could treat.

Figure 15.

- BRIGGS’ BITTERS These Bitters, originally prepared by the late Doct. JOHN P. BRIGGS, or Portland, are decidedly one of the best preparations of the kind which has been offered to the public. They are a warm cordial stomachic; slightly cathartic, and are peculiarly fitted to remove from the stomach and bowels any accumulation of billious matter and to give a vigorous and healthy tone to the organs of digestion. They are now prepared and put up from the original recipe of Dr. Briggs. in his own handwriting, and for sale wholesale and retail by CHARLES B. SMITH, West Market Row, Congress St. Portland. Sold also by Edward Mason & Co., Middle Street; N. B. Folsom, Jr. & Co., City Exchange; and by Agents in various parts of the State. For sale in Augusta by J. E. LADD. N.B. Numerous testimonials of the most flattering character have been received, from which the following is selected, viz: We have used Briggs’ Bitters, prepared by Mr. Smith, and cheerfully add our testimony in their favor. As a remedy in jaundice and other bilious complaints, in weakness of the digestive organs and loss of appetite, in recent colds, and generally as a safe and efficient corrector of the stomach and bowels, we consider them a highly valuable medicine and recommend them as well worthy the attention of the public. Nathaniel Ilsley, Albert Winslow, J. G. Leavitt, Z. Reynolds, E. Daniels, Alpheus Libby. Portland, Jan. 12, 1841. 6w15

By 1845, seven years after his death, Dr. Briggs’ medicine was still popular. The longer time went on, the more ailments were added to the list of conditions his original concoction could treat. This advertisement from the Portland Weekly Advertiser (Figure 16) also notes that Dolly’s brother, Henry Jewett Boynton, was producing the bitters. He was a dentist.

In 1849, yet another Portland-based company was offering “Dr. Briggs’ Vegetable Restorative Bitters” and had added “headache” and “all complaints arising from a bad state of the blood” to the list of treatable ailments.

Figure 16.

- DR. JOHN P. BRIGGS’ ORIGINAL VEGETABLE BITTERS. These BITTERS are recommended for purifying the blood, promoting digestion, exciting a healthy appetite, preventing Costiveness, regulating the Stomach and Bowels, Faintness and Sinking in the Stomach, Nervous and Sick Headache, Drowsiness and Jaundice Complaints, Dyspepsia, &c. &c. They also invigorate the whole system, strengthen the invalid, and give a new tone and vigor to the constitution. N.B. The genuine Briggs Bitters from the original receipt of the late Dr. J. P. Briggs, are prepared by his brother-in-law Dr. H. J. BOYNTON, and for sale at wholesale and retail by BENJAMIN STEVENS, JR., WHOLESALE AND RETAIL DRUGGIST & APOTHECARY, Corner of Brown & Congress Streets, PORTLAND, (Me.,) Where is always kept a very large assortment of DRUGS and MEDICINES, at the very lowest prices. 1mdtw&w aug. 4.

By 1850, Dr. Briggs’ original formula was being made and sold in Boston by a druggist named L. J. Seavy.

He advertised that “Dr. Briggs’ Bitters are acknowledged to be the safest, cheapest, and most effectual remedy ever offered to the public for jaundice...” (and so on).

The picture (Figure 17) is one of the bottles Seavy used during this period; the photo was found on a website for those interested in collecting antique bottles.

Figure 17.

The attraction of La Salle, Illinois

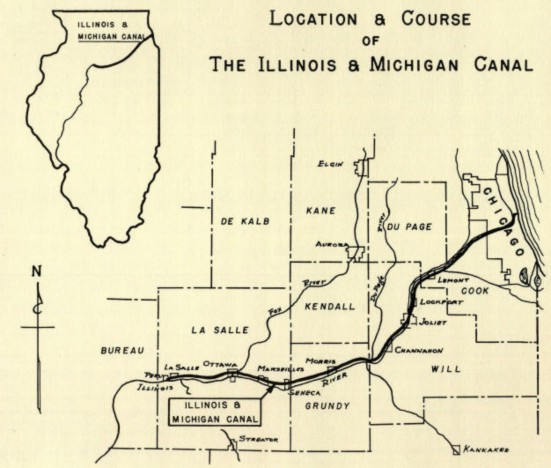

It was members of the Strout family—David and Hannah, David’s father James, and others—who were the pioneers that left Maine for La Salle around 1842. David was a farmer, and family lore is that he was attracted by the inexpensive land (about $1.25 per acre) being offered by The Illinois & Michigan Canal Company in its effort to attract workers. Construction of the canal was already well underway when they arrived, having begun in 1836.

The canal was key to the development of the midwest. Until then, Chicago manufacturers had no easy water route to allow the shipping of products. A canal linking Chicago to the Illinois River at La Salle (with further access to the Mississippi River) was the solution. The canal was completed in 1848, 12 years after it had begun; Chicago’s population and economy significantly expanded, allowing the city to become the center of activity in the midwest. The map of the 96-mile-long canal (Figure 18) is from the archives of the state of Illinois.

Figure 18.

Hannah must have written convincing letters to her siblings encouraging them to head west, for in the early 1850s, her married sisters Jane and Rebecca and their families, as well as unmarried sisters Eliza and Charlotte, moved to La Salle. After 1854 Hannah’s brother William arrived; he’d been living in New York City and likely accompanied their mother Dolly to La Salle. She had just lost her second husband, Simeon Pease, in the summer of 1854. With five of her daughters already in La Salle, there may have been little to keep her in Maine. William and Dolly’s relocation to La Salle made the family nearly complete once again. In the 1860 census for La Salle, Dolly was in the household of her son Dr. William D. Briggs and his family.

Dorothea “Dolly” Fifield (Boynton) Briggs Pease

Finally, we take a closer look at the matriarch of the family. In April of 1838, less than a year after her husband’s death, Dorothea “Dolly” Fifield (Boynton) Briggs married Simeon Pease of Cornish. He was a lawyer who had served in the state senate, was postmaster in Cornish for a short time, and head of a household that included two or three teenage children. He too had lost his spouse less than a year earlier; Mary (Lord) Pease died in 1837.

And of course, he was the man who had passed along the $20 from Dr. John Briggs to Dolly while John was at Lake Champlain, and who then assisted Dolly and her children in the settlement of John’s affairs after his death.

The photo (Figure 19) is of Dolly in later years, courtesy of Steve Strout.

Figure 19.

As noted above, Dolly moved to La Salle after Simeon Pease died. Her death likely occurred after 1860, although it’s frustrating that no vital record of death, no newspaper notice, or any other document has yet been found to confirm her death and burial.

Final resting places

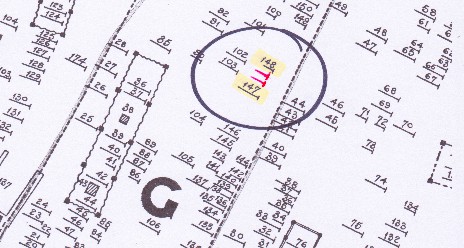

Dr. John Perkins Briggs and his sons Henry H. and William P. Preble were buried at Eastern Cemetery in Portland in the 1830s. As noted above, the doctor and Henry share a marker located at plot G-147, while the remnant of William’s marker is at G-148. Taking a look at the detail of the Section G plot map (Figure 20) reveals that there are two plots (drawn in red ink), not one, between their gravestones.

Figure 20.

We can assume that Henry is buried in one of the plots, but the second unassigned one leaves us wondering if this is the location of another member of the family who died around the same time. Could this be the final resting place of the doctor’s daughter Dorothea, who accidentally drowned at the age of 14?

Since five, possibly six, of Dorothea’s children were buried at the Rockwell and Oakwood Cemeteries in La Salle, it is likely that she too is buried in one of those two locations. The cemeteries abut one another. Rockwell is La Salle’s oldest cemetery, established in 1836. Within 40 years the town needed additional burying space and so the adjoining land was developed as Oakwood Cemetery in 1874.

Eliza Brigg’s husband Sidney Darrow was the Oakwood Cemetery sextant, and in 1878 had a frightening incident that was reported in the August 22 edition of the Chicago Daily Tribune (Figure 21).

Figure 21.

- A VIPER’S BITE. Special Dispatch to The Tribune. LASALLE, ILL., Aug 21. — Sidney Darrow, sexton of Oakwood Cemetery, in this city, was bitten on the left hand day before yesterday by some sort of a poisonous serpent, supposed to be a viper, and for some hours suffered severely, but his life was saved by a copious administration of whiskey.

Graves for Eliza and her sister Jane are found at Oakwood. Their siblings Charlotte, William D. and Hannah are at Rockwell. Grave locations for Rebecca and their mother Dolly could very well be at Rockwell too, although that has yet to be confirmed. Steve Strout’s great-grandfather knew all of the occupants of the Rockwell family lot, but apparently never recorded a plot list. And, sadly, the city of La Salle reports that Rockwell’s records have been lost; community volunteers are doing their best to restore as many of the burial records as possible.

The table (Table 1) provides the list of known burial locations for the Briggs family. Memorial identification numbers for their listings on the Find a Grave website are provided for those interested. Pictures of gravestones are included on Find a Grave for some members of the family; where lacking, I’ve sent requests for photos in the hope that a local volunteer will visit the cemeteries and take pictures to help complete the full picture of this family.

| William Pitt Preble Briggs | Portland, Maine: Eastern Cemetery | 1832 | yes, but just a remnant | 101639375 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dr. John Perkins Briggs | Portland, Maine: Eastern Cemetery | 1837 | yes, eroding but intact, shared with son | 101639374 |

| Henry H. Briggs | Portland, Maine: Eastern Cemetery | 1838 | yes, eroding but intact, shared with father | 101639372 |

| Mary E. (Briggs) Cole | Cornish, Maine: Riverside Cemetery | 1887 | yes, intact, shared with husband | 217447199 |

| Jane H. (Briggs) DeMerritt | La Salle, Illinois: Oakwood Cemetery | 1874 | unsure (requested photo) | 206459245 |

| Eliza (Briggs) Darrow | La Salle, Illinois: Oakwood Cemetery | 1911 | unsure (requested photo) | 206590070 |

| Charlotte (Briggs) Carr | La Salle, Illinois: Rockwell Cemetery | 1857 | unsure (requested photo) | 169501912 |

| William D. Briggs | La Salle, Illinois: Rockwell Cemetery | 1865 | yes, intact | 17702559 |

| Hannah Barker (Briggs) Strout | La Salle, Illinois: Rockwell Cemetery | 1890 | yes, intact | 137714898 |

| Dolly Fifield (Boynton) Briggs Pease | probably in La Salle, Illinois | after 1860 | unknown | none |

| Rebecca Harmon (Briggs) Stuart | probably in La Salle, Illinois | 1898 | unknown | none |

| John P. Briggs (Jr.) | Unknown | after 1854 | unknown | none |

Appendix: Another interesting discovery during research

As noted above, records for the boys born to Dr. John and Dolly Briggs tend to be less available than for the girls. The junior John P. Briggs proved to be the most challenging of all. Records for him are few and far between; those that do exist only give hints as to his life. Given his general lack of presence in the types of records found for his siblings, I’ve made the assumption that he followed in his grandfather’s rather than father’s steps. His grandfather Abiel Briggs was a mariner while of course his father John was a medical man.

Hannah Strout’s grandson Raymond was one member of this family who documented its history. He assembled a notebook of relatives as he worked on the family tree around 1940. Found among the pages is this entry:

John Briggs

wife

Capt. of Chilean Man of War lost

It’s hardly solid evidence, but that it comes from family notes gives credence to the theory that John Jr. spent much of his life at sea.

I found an interesting set of newspaper articles published in Boston from September 1842 through spring of 1843 related to a mariner named John P. Briggs. He was likely in between journeys as he was boarding at the Jefferson House in Boston at the time of the incident. “Our” John would have been about 22 years of age at that time.

While very interesting on its own, this story is included as an appendix since we’re as yet not 100% sure this man was the son of Dr. John and Dolly.

The clipping shown (Figure 22), from the September 17, 1842, Boston Courier, gives a good accounting of the incident.

Figure 22.

- [REPORTED FOR THE COURIER] MUNICIPAL COURT. WEDNESDAY AND THURSDAY, Sept. 14 and 15. Commonwealth vs. John P. Briggs. This was an indictment against the defendant for manslaughter in causing the death of Daniel O’Sullivan, at the Jefferson House, about three weeks since. The facts are briefly these: Briggs, who is a sea-faring man, was staying at the Jefferson House. On the day of the occurrence, Briggs was skylarking in the kitchen with Mary, the cook, who threw him and ran into the washroom. He followed. O’Sullivan, who was idling about there, walked into the washroom and said to Briggs, “Mary can throw you down whenever she pleases” — to which Briggs replied, “She can’t, nor you either.” Briggs then took deceased by the shoulder and turned him around and kicked him. Some words passed between them, after which they grappled, and O’Sullivan was thrown on the floor of the washroom, and in the scuffle or the fall, his ankle-bone was dislocated, and the small bone of the ankle fractured. He lived about five days after the accident, and then died of delirium tremens. It was in evidence that O’Sullivan was a very intemperate man, and that a slight wound would be likely to cause delirium tremens in such a subject. The defense was ably and faithfully conducted by Richard H. Dana, Jr. — but the jury, after twenty-three hours’ consultation, being unable to agree upon a verdict, were discharged. The verdict of the public will be, that the affair was a very foolish and very unfortunate one—and bruisers may learn from it that it is better to leave off scuffling before you begin.

In November, a second jury heard the case against John P. Briggs. The clipping (Figure 23) is from November 24, 1842, and provides the details.

Figure 23.

- In the MUNICIPAL COURT, yesterday, John P. Briggs was tried a second time on a charge of manslaughter, in causing the death of John O’Sullivan. It will be recollected that the case was tried in September, but the Jury did not agree. The accident grew out of a foolish scuffle in the Jefferson House, in which the deceased was thrown and his leg broken; delirium tremens ensued, and he died in three or four days. The Jury returned a verdict of not guilty of manslaughter, but guilty of an aggravated assault. R. H. Dana, Jr. for defendant.

So this John P. Briggs, after two trials, was found guilty of aggravated assault and sent to Boston’s Leverett Street jail. But his trouble did not end there. As detailed (Figure 24), published December 10, 1842, Briggs was caught attempting to break out of jail. For the attempted escape, he was sentenced to three months in the House of Corrections.

Figure 24.

- Attempt to escape from Leverett street jail. — For some time past the officers of the jail have entertained suspicions that the prisoners in cells No. 5 and 7 were at work on their double-grated windows, and they permitted them to proceed unmolested, till Sunday last, when it was discovered that two bars two inches square, had been sawed off in the window of No. 7 and a bar partly sawed in No. 5. A stop was now put upon their operations, and extra chains upon their limbs. Ezekiel S. Kent, charged with coining, and George J. Homer, charged with stealing watches, occupied No. 7, and John P. Briggs, under sentence for causing the death of Daniel Sullivan, and Alonzo T. Chapin, held for stealing, occupied No. 5. If they had got out of their cells in the night, there was nothing to prevent their escaping from the yard. Kent and Homer have confessed, and one of the saws was found in the jail yard, having been thrown from the window.

Final words...

In preparing this manuscript for the graveside ceremony honoring Dr. John Perkins Briggs, I spent many hours on Ancestry.com for census, vital records, directories, and genealogical details, on FamilySearch.org for family tree details, on GenealogyBank.com for the early newspapers of Portland, and on FindaGrave.com for information about the gravestones and cemeteries related to Dr. Briggs and his family. Steve Strout also spent countless hours sifting through boxes of family documents, checking military files on Fold3.com and searching for deeds for Cumberland County, Maine. He kindly forwarded volumes of material to me to include in my files and this paper.

Steve and his wife live in Fort Worth, Texas. He is a 4th-great-grandson of Dr. John and Dolly Briggs and has custody of a large collection of family documents and photographs passed from generation to generation within his clan. He enthusiastically jumped aboard this project and graciously allowed me to include the images of his family in this document. He visited his elderly Uncle John a few times to tap his memory about the family’s history. And Steve served as beta reader for this paper; truly he was “all in” for this work. So while this paper is the result of the concerted effort to learn as much as possible about Dr. Briggs and his family, Steve no doubt has many other branches of his family tree to explore—and many more compelling stories to tell—to bring a spotlight onto this interesting family.

Finally, I want also to thank the following kind people who answered questions, offered expertise, and provided material that helped me put the story of Dr. Briggs to paper:

- Herb Adams, Southern Maine Community College

- Janet Alexander, Spirits Alive (The Friends of Eastern Cemetery)

- Libby Bischof, University of Southern Maine

- Larry Glatz, local historian and expert on veterans’ records

- Tiffany Link, Maine Historical Society

- Tammy Mansfield, Alexander Slidell MacKenzie Chapter, USD 1812

- Mike Murray, City of Portland

- Martha Zimicki, Spirits Alive

References

Description and PDF version: Dr. John Perkins Briggs (1791–1837): A Surgeon in the War of 1812

1 For many years, only the head of household was named in the US census records; all others in the household were simply slotted into age bands (which were adjusted over time) and later in age bands by sex. It was not until the 7th census in 1850 that all members of each household were named. back to text 1

2 Source: 24th Congress, 2nd Session. House of Representatives, Rep. 148, entitled “Doctor John P. Briggs; To accompany bill No. H. R. 872.” Dated January 24, 1837. back to text 2

3 Thomas Smith #1 was born and died in 1729 to Rev. Thomas and Sarah Smith. Three years later (1732) they had Thomas #2, who died 1733. Then in 1735 they had Thomas #3, who survived infancy and lived 40 years. back to text 3

4 The other Portland resident named John L. Briggs was married to a woman named Nancy and I was able to track them sufficiently enough to eliminate them as relatives of Dr. John. Likewise for William, the rigger, who was a resident of Portland long before Dr. John moved his family from Cornish.back to text 4