The Desecration of Judge Potter's Grave and the Lads Who Committed the Crime

Tenth in a series of Occasional Papers about Eastern Cemetery in Portland, Maine

by Ron Romano

© 2022

Figure 0. Detail from the Cumberland County sheriff’s log, September 1866, courtesy of Maine Historical Society

-

Destroying and removing a fence or railing in the Eastern Cemetery

In September 1866, four teenaged boys were arrested for vandalizing the Eastern Cemetery grave of a celebrated Portland man, the Honorable Barrett Potter, who had died less than a year before. Vandalism at Eastern Cemetery has been a problem for over two hundred years; the first documented case involved the toppling of many gravemarkers in 1816. The four teenagers linked to the 1866 event were ultimately punished for their actions and Judge Potter was later removed from Eastern Cemetery and reinterred across town at Evergreen Cemetery. Newspapers from the fall of 1866 provide the basic story of the event and its aftermath, but this paper takes a deeper dive, detailing the crime, its victim, and some troubling backstories of the four young vandals. With ties to the Longfellows, anti-Irish sentiment of the mid-1800s, and even a grizzly murder, the full story unfolds here….

Contents

- The Crime – Desecration of a Grave

- The Victim – Judge Barrett Potter

- The Longfellow Link

- The Young Criminals

- The Cemetery Vandals – Punishment

- The Wrap-up

- Published Sources

- Other Sources

- References

The Crime – Desecration of a Grave

In August 2022 while transcribing early Cumberland County sheriff’s records, Cindy Murphy of the Maine Historical Society came across a record of the arrest of four males for desecrating a grave at Eastern Cemetery. Her interest in this particular record was that the victim of the crime—though deceased—had ties to the Longfellow family. After discovering that the victim’s gravestone is located at Evergreen Cemetery, not Eastern Cemetery, and knowing of my work to document the history of Eastern Cemetery, she contacted me to see if I could help her sort this out. Cindy had cast her line. I took the bait. And I began my research to put this story together.

The entry in the county records detailed the crime as “Destroying and removing a fence or railing in the Eastern Cemetery… enclosing the burial place of the late Barrett Potter.”

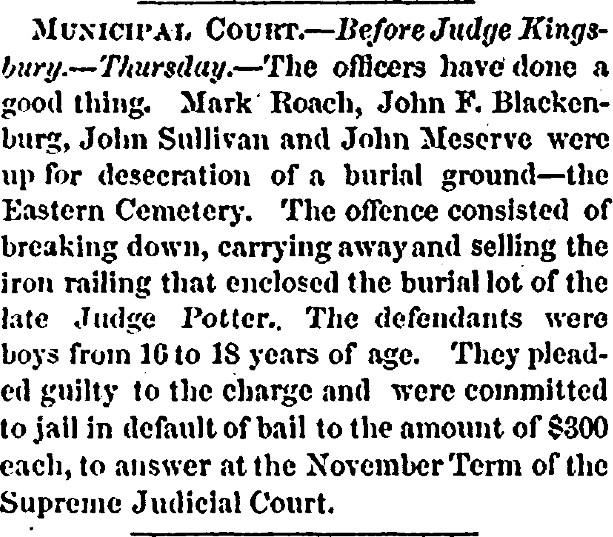

While that entry in the sheriff’s log summarized the vandalism, a notice in the September 21, 1866, Daily Eastern Argus (Figure 1) provided greater detail about their actions.

Figure 1.

-

MUNICIPAL COURT.—Before Judge Kingsbury.—Thursday.—The officers have done a good thing. Mark Roach, John F. Blackenburg, John Sullivan and John Meserve were up for desecration of a burial ground—the Eastern Cemetery. The offense consisted of breaking down, carrying away and selling the iron railing that enclosed the burial lot of the late Judge Potter. The defendants were boys from 16 to 18 years of age. They pleaded guilty to the charge and were committed to jail in default of bail in the amount of $300 each, to answer at the November Term of the Supreme Judicial Court.

Three months later, the December 7, 1866, Portland Daily Press, finetuned the crime even further, noting that the boys had stolen “twelve iron rods” from the cemetery.

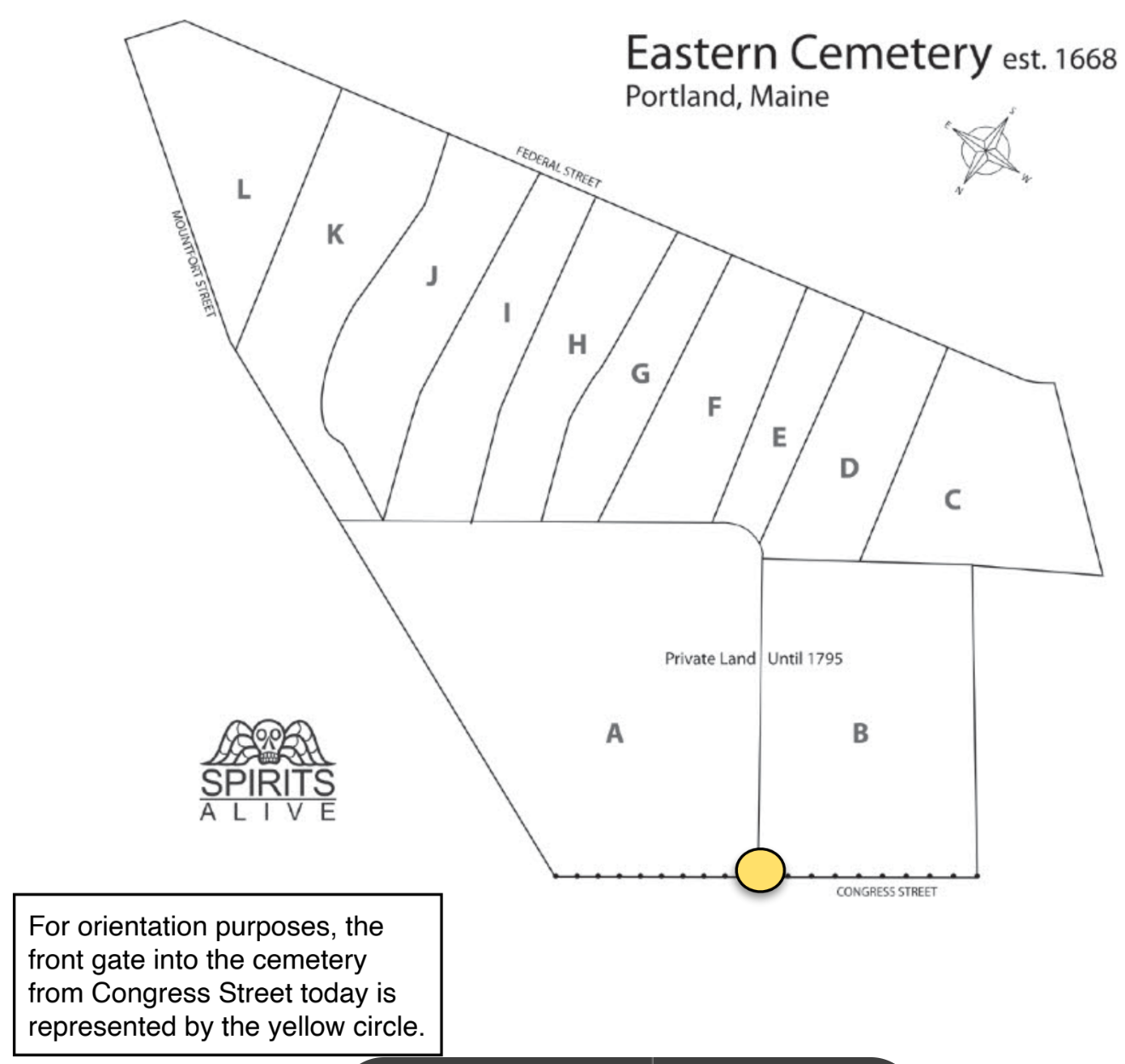

The reference to “twelve iron rods” provides a clue to the original burial place of Judge Potter. In the older part of the cemetery (that is, before 1795 and comprised today of the sections labelled C through L on the map) (Figure 2), there were few fenced family lots. This is because the original burying ground was truly public space, open to Portland’s families to use for the burial of their kin. With few rules and little order to the use of this common ground, bodies were laid to rest wherever an empty plot could be found; perhaps only a few well-to-do families were able to claim enough space to fence off for their future use. But when sections A & B were added to the cemetery in 1795, the town better organized the space to maximize the number of burials and to allow families to set off family lots of four, six, eight, and even ten plots. Some families enclosed those lots with fences.

Figure 2

-

Eastern Cemetery, est. 1668, Portland, Maine. For orientation purposes, the front gate into the cemetery from Congress Street today is represented by the yellow circle.

The exact location of Judge Potter’s fenced lot is no longer known, since his family was later removed to Evergreen Cemetery. His lot may have then been recycled for other burials. Today we find evidence of about three dozen such family lots—in various degrees of condition—in the new part of the cemetery (again, Sections A & B on the map (Figure 2), closest to Congress Street). These enclosed lots consist of granite posts fitted with metal rails. Generally, each pair of posts holds two rails. A smaller family lot of four to six graves would therefore have eight rails (four posts). A larger family lot of eight to ten graves would have 12 rails (six posts).

The photo below (Figure 3) shows another family’s eight-grave lot enclosed by six posts with twelve iron rods in Section B—certainly this is how Judge Potter’s lot looked before its desecration.

Figure 3

During the 1860s, about a dozen men worked in Portland making gravestones. Referring to themselves as stonecutters and marble workers, they advertised their wares in newspapers, directories, and even cemeteries. With great competition, it was common practice to sign the gravestones they made so that passersby could see the style and quality of their work. Joshua T. Emery was one such maker.

Figure 4 is his advertisement from 1866, the year of the desecration, Emery suggested that potential customers could visit Evergreen Cemetery1 to see firsthand the quality of his work. He’s the only maker in this decade whose ads mentioned that he offered “designs for cemetery lots.” Others certainly were doing so as well, but he may very well have been the man who created the posts and rails that set off the Potter family lot from the many other graves at Eastern Cemetery.

Figure 4

-

STONE CUTTING,

JOSHUA T. EMERY

Has his headquarters still at the

FOOT OF PEARL STREET, BACK COVE,

Where he is prepared to execute good work for stores and houses at compensating prices. Particular attention paid to executing Monuments and designs for Cemetery lots; for the Style and finish of which he refers to work done by him at Evergreen Cemetery, Westbrook.

The Victim – Judge Barrett Potter

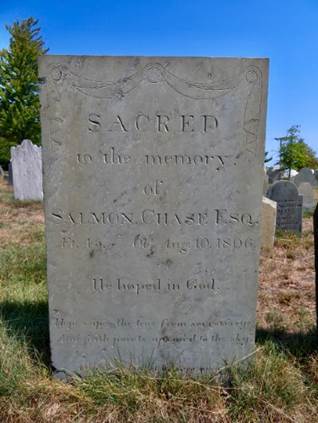

Barrett Potter was born in Lebanon NH in 1777, being in the sixth generation of Potters in America. His third-great grandfather, William Potter, had arrived in Boston with his brother and their families in 1637. Barrett attended Dartmouth College, receiving his degree in 1796. By 1801 he was working in the field of law and moved to Maine. At age 29 in 1806 he became law partner of Salmon Chase in Portland, but Chase died just two months after their partnership formed. Barrett Potter became guardian of Chase’s children, and as executor of Chase’s estate he would have visited the stone shop of Bartlett Adams at the corner of Federal and Fish (now Exchange) Streets in order to procure the gravemarker that survives to this day on Salmon Chase’s grave at nearby Eastern Cemetery (Figure 5). The square-top slate is decorated with a simple bunting, a typical design hand-carved by Adams and the other men in his shop in the early 1800s.

Figure 5

-

SACRED

to the memory

of

SALMON CHASE ESQ.

AEt. 45. Obt. August 10, 1806.

He hoped in God.

William Willis, who profiled Barrett Potter in “A History of the Law, the Courts, and the Lawyers of Maine…” (published 1863, shortly before Potter’s death), noted that Barrett Potter was one of just a half-dozen lawyers in Portland at this time. With the town’s extensive maritime-based economy, consisting largely of the export of lumber and provisions and the import of sugar, molasses, and rum from the West Indies, the town’s lawyers had plenty of business, allowing Barrett Potter to prosper.

In 1822, at age 45, Barrett Potter was appointed Judge of Probate, an office he held for 25 years. He retired from that job at age 70 in 1847.

Barrett Potter married only once, in 1809 to Ann Titcomb Storer, a daughter of his colleague Woodbury Storer. Willis noted that, “Mrs. Potter was a lovely woman, but of frail and delicate organization.” She died at age 40 in 1821, very possibly due to complications from childbirth. She has a grave marker at Evergreen Cemetery today, but she was no doubt originally interred at Eastern Cemetery in the Judge’s lot, as her death preceded the establishment of Evergreen.

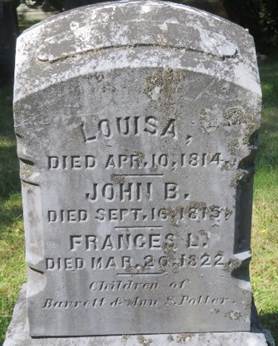

According to Willis, Barrett and Ann had only three daughters, but Willis must have been referring only to those children who had survived their infancies. Gravestones document three additional children who died at very young ages, in 1814, 1815, and 1822.

That Judge Potter and his family were removed from Eastern Cemetery to Evergreen Cemetery is not at all unusual. They were among 600 or more who were similarly removed from Eastern Cemetery as it fell out of favor, and reburied elsewhere in the mid- to late-1800s2

In addition to the Judge, who died in 1865 and therefore was likely the last in his family to be interred in the Eastern Cemetery lot, I suggest these other family members were originally buried at Eastern (in the order of their interment), but later removed to Evergreen Cemetery:

- daughter Louisa, who died April 10, 1814

- only son John B., who died September 16, 1815

- wife Ann (Storer) Potter, who died in 1821

When we examine the five matching marble gravestones at Evergreen Cemetery, it’s clear they were produced in the mid-1800s versus the 1814 to 1821 period reflective of the above deaths. If individual markers were present in the Eastern lot, they certainly would have come from the nearby shop of Bartlett Adams, who operated the only stonecutting shop in Portland at the time, and they most likely would have been made of slate.

The five stones at Evergreen are found in a single line across adjoining lots M-156 and M-157 and are detailed below. Two of the five are pictured (Figures 6 and 7):

- Judge Potter, who died 1865

- Ann (Storer) Potter, who died 1821

- A shared stone that’s inscribed “Children of Barrett & Ann S. Potter” names Louisa, died April 10, 1814; John B., died Sept. 16, 1815; and Frances L., died March 20, 1822. While I believe that Louisa and John B. were removed from Eastern with their parents, Frances is likely buried in New Hampshire. She died just a few months after her mother. It’s possible that following Ann’s death, Judge Potter brought his children to his hometown of Lebanon, New Hampshire, to be with family. But Frances must have died there, since a small slate gravemarker is found at the School Street Cemetery in Lebanon in her name. It’s inscribed “child of Barrett and Ann Potter.”3 This means that her memorialization at Evergreen Cemetery is a cenotaph (that is, a stone placed on a plot as a memorial to a person who is buried elsewhere).

- Eliza, died 1890 unmarried at age 80. She was documented as one of the daughters by William Willis, who in his 1863 profile of the Judge wrote that Eliza was “now living with her father unmarried.”

- Mary (Potter) Longfellow. Mary’s stone is definitely also a cenotaph as you will shortly see.

Figure 6

-

BARRETT POTTER

DIED

NOV. 16, 1865

AET. 88.

Figure 7

-

LOUISA,

DIED APR. 10, 1814.

JOHN B.

DIED SEPT. 16, 1815.

FRANCES L.

DIED MAR. 20, 1822.

Children of

Barrett & Ann E. Potter

The sixth child, Margaret, is not memorialized at Evergreen with her parents and siblings. She lived to 1901 and was buried with her husband and family in Newton, Massachusetts.

The Longfellow Link

When Barrett Potter became Salmon Chase’s law partner in 1806, one of the few other lawyers in town was Stephen Longfellow. His wife Zilpah (Wadsworth) Longfellow was at that time pregnant with the future world-famous poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. So Barrett Potter and Stephen Longfellow were certainly well acquainted by occupation. But a deeper connection between the two families would be cemented in place a quarter of a century later.

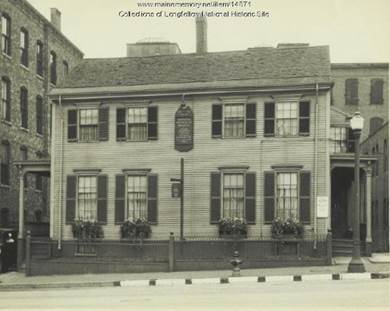

In his book about Longfellow, John Babin documents the friendship between Barrett Potter and Stephen Longfellow, and notes that their children, Mary Potter and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, were friends growing up. They became engaged to marry in 1830, and Babin’s book includes the text of a letter the future poet wrote to Judge Potter, expressing his gratefulness to the Judge, “for the confidence you have… in placing in my hands the happiness of a daughter… I hope that you may never… think that your confidence has been misplaced.” The following year, in 1831, Judge Potter became the future poet’s father-in-law when he hosted Mary and Henry’s wedding in the parlor of his home on Free Street.

Figure 8. Image of Judge Potter's home, the site of the wedding of his daughter to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1831. The photo from 1940 is in the collections of the Maine Historical Society.

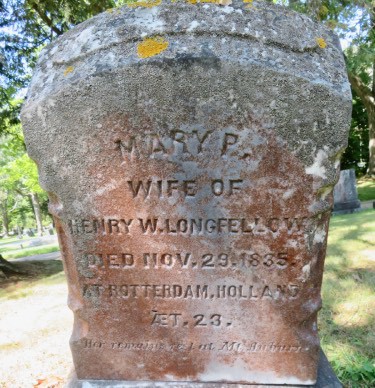

Early in 1835, the couple made their way to New York, boarding a ship bound for London. After a month in London, they travelled to Germany, Denmark, and Sweden. Mary was by then pregnant with their first child, but not fairing well. While in the Netherlands, she miscarried and ended up losing her life in November. Babin provides us with the text of a letter Henry wrote home regarding this:

I have had her body embalmed – enclosed in a leaden coffin, and that again in an oaken one – and the whole put into a case, and directed to (your) care. It will leave Rotterdam on Wednesday next, by the Brig Elizabeth, Capt. Long. Have the goodness to pay the charges; and to have the body deposited, encased as it now is, in the Tomb of the Mount Auburn Cemetery. I have heard there is such a tomb for the safe-keeping of bodies, until a time as preparations for their final burial can be made. On my return I shall purchase a spot in Mount Auburn for a tomb. Let me hear by letter of the safe arrival of the body.

Henry did not accompany his wife’s body back to the United States but instead stayed in Europe for some time, returning to Massachusetts in 1836 to begin his professorship at Harvard University. Many years later, Longfellow himself was laid to rest at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. His large granite memorial is surrounded by bronze plates resting flush to the ground; on one of these we find inscribed the name and date of his first wife, Mary Potter Longfellow. Although Judge Potter and his daughter Eliza far outlived Mary and knew that she’d been interred at Mount Auburn, they had a stone erected for her at Evergreen in the family lot. Inscribed on that cenotaph we find:

Mary P.

Wife of

Henry W. Longfellow

Died Nov. 29, 1835,

At Rotterdam, Holland

(At the age of) 23.

Her remains rest at Mt. Auburn

Figure 9. The family lot for the poet and wife at Mount Auburn

Figure 10. The cenotaph for Mary at Evergreen Cemetery in Portland

Figure 11. A painting of Mary Potter Longfellow (Wikipedia)

The Young Criminals

The sheriff’s records named the four boys arrested for the desecration of Potter’s lot as:

- John McGuire

- John Sullivan

- John F. Blackenburg

- Mark Roach

The newspapers that followed this story between September and December 1866 referred to them as “lads” and “boys,” one noting they were between 16 and 18 years of age. Assuming that to be accurate, it narrows down their years of birth to 1848, 1849, and 1850. To learn more about the young criminals, that was my starting point. Checking directories, census files, newspapers, and genealogical records of the mid-century, I hoped to track these four down. The effort led to mixed results….

John McGuire

The most challenging boy to identify is John McGuire, primarily because his name was recorded with at least five different spellings:

- McGuire: In the sheriff’s log and the Daily Eastern Argus in December 14, 1866

- Maguire: Portland Daily Press, December 7, 1866.

- Meguier: Portland Daily Press, December 14, 1866.

- McGwin: Portland Daily Press, September 21, 1866.

- Meserve: Daily Eastern Argus, September 21, 1866.

The first three are easy to accept as alternate spellings of the same surname, but McGwin is a bit of a stretch from them and Meserve just seems to be an error instead of a misspelling. I then checked the 1866 Portland directory and found only one of these surnames recorded — McGuire. In the 1850 census for Portland I found a two-year-old John McGuire, son of Irish immigrant laborer James and his wife Jane. His year of birth, 1848, makes his age 18 in 1866, within the range reported in the newspaper. In the 1870 census for Portland, a 19-year-old John McGuire was living with his Irish immigrant parents John and Dorothy and working as a painter. His inferred year of birth was 1851, just out of range from the newspaper report. Was the young cemetery vandal one of these two boys? It remains an uncertainty. But what is clear is that he and another of the gravesite vandals got themselves into some trouble again in 1867.

John Sullivan

There were many Irish families named Sullivan in Portland in the 1860s. Local historian Matthew Jude Barker estimates that between 3,000 and 4,000 Irish immigrants and their families were living in Portland in the 1860s, comprising up to 15 percent of the population. In the 1866 Portland directory there were nine adult men named John Sullivan. The 1860 and 1870 censuses for the city document many more underage John Sullivans. So the lack of any other details about the John Sullivan named in the sheriff’s log and subsequent newspaper articles means that it’s nearly impossible to know exactly who this John Sullivan was.

With that uncertainty as a backdrop, I offer two possibilities. Vital records exist for two boys named John Sullivan who were born in Portland in 1849. Both of their fathers were Irish immigrants working as laborers, and their dates of birth were just three weeks apart (June 17 and July 9). These two, if still living in Portland in 1866, would have been 17 at the time of the cemetery incident—within the age range reported in the newspaper at the time.

There’s also a dizzying array of notices of crimes, arrests, fines, and imprisonments under the name John Sullivan in Portland in the newspapers published in the two years following the cemetery incident. But again, since those notices omitted ages, names of parents, and links to past crimes, it’s impossible to know for sure if any of those John Sullivans were the same one who vandalized Potter’s gravesite. One notable exception was found regarding an incident that occurred six months later.

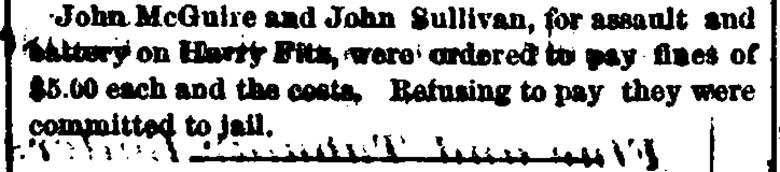

The Portland Daily Press of May 15, 1867, reported that John Sullivan and John McGuire were arrested for assault and battery. They are surely the same two who had vandalized Judge Potter’s grave. For this crime, they were each ordered to pay $5 plus court costs. And as was the case regarding the cemetery crime, since they did not pay their fines and fees, they spent time in jail.

Figure 12

-

John McGuire and John Sullivan, for assault and battery on Harry Fits were ordered to pay fines of $5.00 each and the costs. Refusing to pay they were committed to jail.

John F. Blackenburg

With his more unique surname, this teenage vandal left behind a much richer paper trail, allowing for this profile. Most records used the spelling shown above, but there were plenty of records that used alternate spellings, including Blackenburgh, Blankenburg, Blankinberg, Blankinburg, Blankingburg, and Blankenbury. For his profile, I use the version found in the sheriff’s log.

John was born in 1847 in Massachusetts to an immigrant father who had been born at sea and a mother from Maine. At age 14 or 15 in 1861, he joined the navy as a “second class boy” in the Maine infantry, Company A, 14th regiment. His naval service lasted three years, serving on the vessels Ohio, Sabine, North Carolina and Ticonderoga. A stint in the army for a few months does not appear to have included any action. In the 1866 Portland directory he was recorded as working as a seaman—not unexpected given his recent years serving in the navy.

In November of 1866, two months after vandalizing the cemetery, 19-year-old John filed his intention to marry 18-year-old Alice J. Quinn. Her family was originally from Massachusetts, but had been in Portland for at least 15 years. As a result of his marriage, one might expect that John’s focus would have shifted to settling down, starting a family with Alice, and ensuring that he could provide for the both of them. Yet just a few months after his wedding, he was charged with assault and battery on a man named H. J. Chisholm. He pleaded “not guilty” but the judge found him guilty of the charge and fined him $9. A year later, he was again in court for a complaint of assault and battery against another man, found guilty, and fined $5 plus court costs.

The 1870 census for Portland documents John, working as a house-lather, and Alice, age 22, living in the household of his mother, Hannah Bodwell. Despite being married for over three years, John and Alice had no children. Around the same time the census was recorded, John found himself in a bit of trouble again—he was in possession of a velvet hat that had been reported stolen from a store on Cumberland Avenue days earlier.

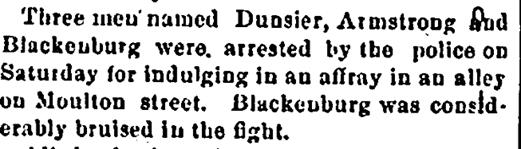

John continued to create trouble for himself in 1871. In August he was arrested for “indulging in an affray in an alley on Moulton Street.” The newspaper (Figure 13) noted that “Blackenburg was considerably bruised in the fight.” Then in October, he appeared in court for his failure to pay a man $18 for a horse. His defense was that the transaction had taken place on a Sunday, when such business was not valid, and that the horse was not as promised by the seller. The judge ruled in favor of the plaintiff, and ordered John to pay the $18. In December came a charge of drunkenness and disturbing the peace.

Figure 13

-

Three men named Dunsier, Armstrong and Blackenburg were arrested by the police on Saturday for indulging in an affray in an alley on Moulton street. Blackenburg was considerably bruised in the fight.

Between 1870 and 1880 Alice died, though details are not found. As well, no records are found regarding children from her marriage to John. The 1880 census recorded John still living with his mother and one boarder. Now in his early thirties, John had apparently finally settled down, managing to avoid any further mention in the newspapers of brawls, batteries, or bruises. In fact, on a more positive note, in 1881 a notice appeared in the paper of an upcoming rowboat race John was to run against another man. Bets were being taken for $5 per side.

From the late 1880s until the 1910s, John lived in the same place, boarding at the rear of 202 Washington Avenue. Once his mother passed, his sister Mary and her husband became the landlords of the property. Listed living with him in the mid-1890s was Hannah Blackenburg, a laundress. Through these decades John continued to work as a house lather. He had never remarried after Alice’s death, despite still being a young man in his thirties then. John died in 1913 at the age of 67 of stomach cancer. He was buried at Portland’s Forest City Cemetery, (located in South Portland) and his grave there is marked with a stone that’s inscribed with his Civil War era service details.

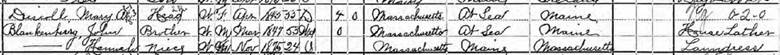

Is She, or Isn’t She?

There's one lingering question about that Hannah Blackenburg just mentioned… Could she actually have been John and Alice’s daughter? They were married in 1866, had no known children in 1870, and Alice died sometime between 1870 and 1880. According to a later census, Hannah’s year of birth was 1875. Perhaps she was their child, and perhaps Alice had died due to complications of childbirth. It’s compelling that this girl’s name was Hannah, the same as John’s mother.

The 1900 census for Portland has John’s 55-year-old sister Mary Driscoll as the head of the household at the rear of 202 Washington Avenue. With her there is her “brother” John Blackenburg at age 53, and her “niece” Hannah Blankenburg at age 24. Obviously if Hannah was John’s daughter, she would be recorded as Mary’s niece in this census. But she might also have been the child of a brother of John and Mary. It’s a bit odd (almost creepy)—but not out of the range of possibilities—that John and Hannah would have shared a home for a dozen years as uncle and niece. Far less questionable would be a home for a father and daughter.

Figure 14. Detail from the 1900 census for Portland

-

Row 1: Driscoll, Mary A, Head, W, F, Apr, 1845, 53, D, 4, 0, Massachusetts, At Sea, Maine. Row 2: John Blankenburg, Brother, W, M, Nov. 1849, 53, Wid, 0, Massachusetts, At Sea, Maine, House Lather. Row 3: Hannah, Niece, W, F, Nov. 1925, 24, U, Massachusetts, Maine, Massachusetts, Laundress.

In that census, John is also recorded as being a widower, which we know is true, but to complicate things a bit further, in the column entitled “Mother of how many children” the census taker placed a “0” next to John’s name (and no entry on the next line for Hannah). John is the only male on that page with an entry under the “mother of…” column. Because he was a widower, had the census taker recorded his offspring (or lack of) in the absence of having a wife to answer this question? Or did the census-taker intend to place that “0” on the following line for Hannah?

If Hannah was John and Alice’s child, and if Alice died at the time of her birth, John may have handed his newborn daughter over to relatives in Massachusetts to raise. As a single father working in labor, he surely would not have easily been able to raise her on his own. Then, when Hannah reached an age of being able to find work she moved back in with her father in Portland. Hannah’s first appearance in the Portland directories at John’s address is 1896, when she was 21. If she was his daughter living with him through her teenage years she would not have been separately listed in the directories (until she reached adulthood).

Finally, I found a record from Boston in November of 1875, of the birth of a Hannah Blackenburg to James and Ellen Blackenburg. In the 1880 Boston census she is listed as their seventh child. Head of household James was reported to have been born in Maine. Then in Portland in the 1900 census we find Hannah with John, with a place of birth listed as Massachusetts. This adds credibility that she was his niece, not daughter. Still, for me, the answer to the question posed at the top of this section, “Is she or isn’t she?” remains a coin toss.

Mark Roach

The most compelling story of the lives of the four cemetery vandals is that of Mark Roach. His father was John Roach and his mother was Bridget King, her surname at the time of marriage being that of her first husband. There is a Portland vital record of intention of marriage in January of 1850 for John Roach and “Mrs. Bridget King.” Mark was presumably their first child, born at the end of 1850, but Bridget had also brought at least three children into this marriage from her first marriage to Mr. King. In the 1852 directory, John Roach was recorded as a laborer, living near Gorham’s Corner, then known to be a neighborhood overcrowded with Irish immigrants.

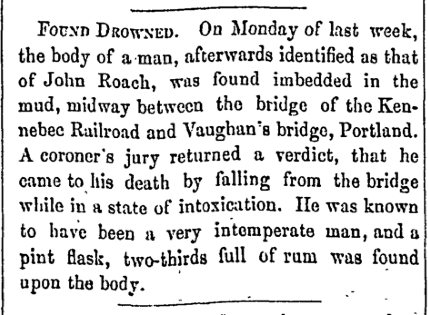

His untimely and accidental death came in 1854 and was reported in the newspaper as related to his state of intoxication (Figure 15). One paper even made light of his death, ending the notice with the line “In other words – RUM DID IT.” This was one of many, sometimes subtle, examples of the general ill will against Irish immigrants at the time. Often portrayed in the news as drunkards, filthy, and unruly, there was some resentment among the majority (primarily of English heritage) that the Irish immigrants were second-class people who were stealing jobs from the locals, increasing crime in the city, and degrading the community as a whole. We know now that many of the Irish immigrants were just trying to escape the desperate situation of their motherland, looking for an opportunity to make a fair wage and support their families.

Figure 15

-

FOUND DROWNED. On Monday of last week, the body of a man, afterwards identified as that of John Roach, was found imbedded in the mud, midway between the bridge of the Kennebec Railroad and Vaughan’s bridge, Portland. A coroner’s jury returned a verdict, that he came to his death by falling from the bridge while in a state of intoxication. He was known to have been a very intemperate man, and a pint flask, two-thirds full of rum was found upon the body.

For five-year-old Mark, his brother Michael, and at least three siblings from Bridget’s first marriage, this must have been a time of great struggle to survive. Three years after John Roach’s death, Bridget married for the third time, to Patrick Griffin, also an Irish immigrant living at the time in Portland. Bridget had at least two more children with Patrick, in 1858 and 1860. This blended family of nine (or more) relocated to Lewiston sometime before 1860, as they were recorded there in the 1860 census, with Patrick working as a day laborer.

It’s hard to know what life was like for 12-year-old Mark Roach in Lewiston in 1862, but the events of Sunday, February 23, 1862, would change his life forever. The story is best told in the Lewiston Evening Journal the following day, and is included here in its entirety.

Figure 16

-

Terrible Tragedy.

An Irishman named Patrick Griffin, who lives in a small house above the depot of the Androscoggin and Kennebec Railroad, near the Foundry, murdered his wife by cutting her throat, on Sunday night about half past ten o’clock. It appears that Griffin, who is a miserable drunken fellow nearly 40 years of age, has frequently been in jail for drunkenness and abuse of his family, and that he had many times threatened to kill his wife for causing, as he alleged, his arrest. The neighbors say that he was frequently intoxicated, and as frequently abused his wife, who was a most industrious and respectable woman, of about 38 years, with 7 children, 5 of whom she had by her first and second husbands (Griffin being the third), and two by the present one. Sunday night Griffin was not intoxicated, as it appears, but nevertheless he commenced abusing his wife, and threatening her life. About 10 o’clock in the evening she was called by her married daughter who, with an infant, occupied one of the rooms in the second story of the house, to bring her some medicine for the child. Having prepared it, Mrs. Griffin, accompanied by her own child of one or two years, went upstairs to do the errand.

Figure 17

-

In going to her daughter’s room, she had to pass through a very small bedroom at the head of the stairs. Griffin, it appears, followed his wife, and overtook her in this small bedroom, where he clinched her and a struggle followed, in which he threw her over a chest, and in this posture cut her throat in a most horrible manner, severing the windpipe and all of the blood vessels on the right side of the throat, and reaching the spinal column. As a razor case was afterwards found in the house, it is supposed that a razor was the weapon used. The noise of the struggle alarmed the children of the houses and they fled, some of them going to the house of officer Hamlin and notifying him.

Officer H. hurried to the scene, but the house was deserted. Borrowing a lantern of some neighbor who had been aroused by the outcry, he went into the lower room, then up the stairs, where a terrible scene met his eyes. There, stretched across an old chest, lay the lifeless body of the murdered wife, and under her head a pool of blood. On some old bed clothes, piled up in the corner of the room, was the child of the woman, which had been thrown there in the struggle. Lifting the woman’s body, he found that life had already departed. Under the body he also found a broken candle which the woman had in her hand when she went up the stairs, and which had been extinguished in the struggle.

Figure 18

-

Officer Hamlin caused men to be distributed at all the points where the murderer would be likely to attempt to escape and then sent for Officers Parcher and Tarbox to come to his assistance. These officers soon came, and in passing the depot, a man suddenly showed his head at the door of an empty box car standing on one of the side tracks, and at the same time cried out, “You needn’t hunt any more; I’m the man!” immediately jumping from the car and coming toward the officers. They at once arrested him, and lodged him safely in the Auburn jail.

This (Monday) morning, Coroner Hamlin summoned a Jury of Inquest, consisting of Messrs. A. K. P. Knowlton, Foreman, Eli Edgecomb, W. R. Frye, Warren Coffin, I. N. Parker, and Josiah Day, who assembled at Griffin’s house, where the body lay, at 10 o’clock.

Figure 19

-

Dr. Edgecomb and Martin examined the wound, and testified as to its mortal character. The Jury will undoubtedly bring in a verdict in accordance with the foregoing facts which we have obtained from the officers making the arrest.

This is the third murder committed in our place within eight months past!

Just two months later, Mark’s stepfather Patrick Griffin was back in court to face a jury of his peers.

Again, because the story is best told today in the words of the time, I include the entire column as printed in the Lewiston Evening Journal on April 24, 1862.

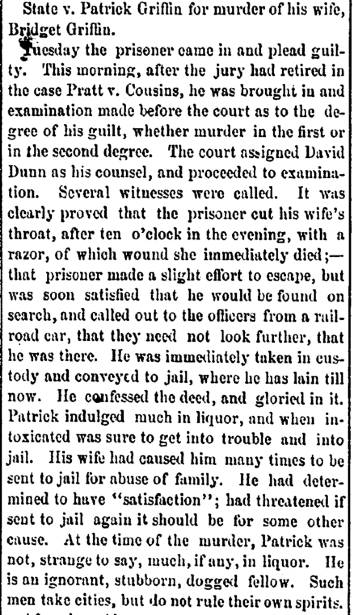

Figure 20

- State v. Patrick Griffin for murder of his wife, Bridget Griffin.

Tuesday the prisoner came in and pleaded guilty. This morning, after the jury had retired in the case Pratt v. Cousins, he was brought in and examination made before the court as to the degree of his guilt, whether murder in the first or second degree. The court assigned David Dunn as his counsel, and proceeded to examination. Several witnesses were called. It was clearly proved that the prisoner cut his wife’s throat, after ten o’clock in the evening, with a razor, of which wound she immediately died; — that prisoner made a slight effort to escape, but was soon satisfied that he would be found on search, and called out to the officers from a railroad car, that they need not look further, that he was there. He was immediately taken in custody and conveyed to jail, where he has lain till now. He confessed the deed, and gloried in it. Patrick indulged much in liquor, and when intoxicated was sure to get into trouble and into jail. His wife had caused him many times to be sent to jail for abuse of family. He had determined to have “satisfaction”; had threatened if sent to jail again it should be for some other cause. At the time of the murder, Patrick was not, strange to say, much, if any, in liquor. He is an ignorant, stubborn, dogged fellow. Such men take cities, but do not rule their spirits.

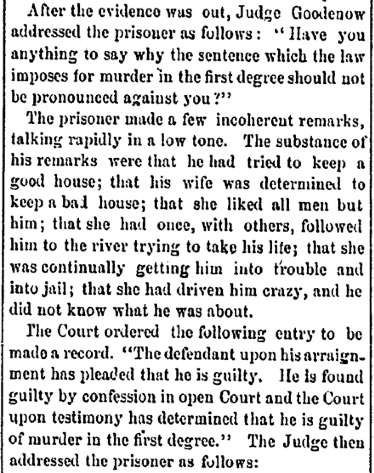

Figure 21

- After the evidence was out, Judge Goodenow addressed the prisoner as follows: “Have you anything to say why the sentence which the law imposes for murder in the first degree should not be pronounced against you?”

The prisoner made a few incoherent remarks, talking rapidly in a low tone. The substance of his remarks was that he had tried to keep a good house; that his wife was determined to keep a bad house; that she liked all men but him; that she had once, with others, followed him to the river trying to take his life; that she was continually getting him into trouble and into jail; that she had driven him crazy, and he did not know what he was about.

The Court ordered the following entry to be made a record. “The defendant upon his arraignment has pleaded that he is guilty. He is found guilty by confession in open Court and the Court upon testimony has determined that he his guilty of murder in the first degree.” The Judge then addressed the prisoner as follows:

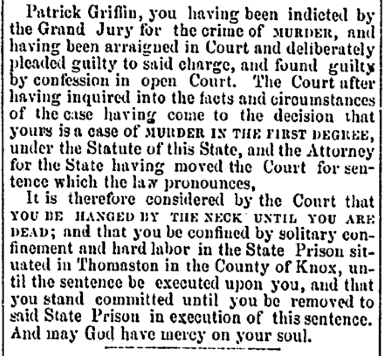

Figure 22

- Patrick Griffin, you have been indicted by the Grand Jury for the crime of MURDER, and having been arraigned in Court and deliberately pleaded guilty to said charge, and found guilty by confession in open Court. The Court after having inquired into the facts and circumstances of the case having come to the decision that yours is a case of MURDER IN THE FIRST DEGREE, under the Statute of this State, and the Attorney for the State having moved the Court for sentence which the law pronounces,

It is therefore considered by the Court that YOU BE HANGED BY THE NECK UNTIL YOU ARE DEAD; and that you be confined by solitary confinement and hard labor in the State Prison situated in Thomaston in the County of Knox, until the sentence be executed upon you, and that you stand committed until you be removed to said State Prison in execution of this sentence. And my God have mercy on your soul.

Griffin was indeed sent to the state prison at Thomaston, where he was still incarcerated at the age of 48 according to the 1870 census. In 1876, Maine abolished capital punishment for a few years. It is likely that having been spared the noose already for 14 years—between 1862 and 1876—his sentence was converted from “death by hanging” to “life in prison.” In the 1880 census for Thomaston, Maine, we again find him accounted for. Under the spelling of Griffen, we find an entry for Patrick at the age of 58 living at the state prison and working as a laborer. Since the 1890 census is not available, the next census from 1900 was checked, but no matches were found. This suggests Griffin died between 1880 and 1900.

So… what happened to Mark Roach following the grisly murder of his mother? The answer again is found in a newspaper article published eight months after the murder.

In October 1862, Bridget R. Mulkearny appeared in court after filing a petition for Habeas Corpus4 for Mark and Michael Roach. She claimed to be their aunt—the sister of Mark’s and Michael’s father. It was noted that the boys had been orphaned as a result of the murder of their mother by their step-father, Patrick Griffin. They had been “thrown upon the town of Lewiston, who transferred them to Portland, and the authorities of Portland bound them out to Michael Gannin.” The court granted her petition, and Michael Gannin appeared in court with the boys. Bridget claimed that her father (the boys’ grandfather) was willing and able to care for the boys. She complained that Gannin “keeps them at work in the factory, takes their wages which may as well go to their relatives as a stranger.” The newspaper reported that the boys spoke for themselves and professed themselves content to remain with their master (Gannin). The judge sided with the defendant, and ordered the boys back into Gannin’s custody.

According to the 1866 Portland directory, “M. Gannon” was a harness maker located at 121 Commercial Street. No listings under the spelling of Gannin are found.

Being fatherless at age five, witness to his mother’s murder at 12, living in a home with an abusive step-parent, forced to work in a factory in his early teens, and basically having to find his own way in life without the benefit of loving, caring adults to support him, it is easy to understand how Mark Roach could have became involved with the other three boys in the theft of gravesite rails at Eastern Cemetery in 1866. But unlike his three partners in crime, his name did not appear in local newspapers for petty crimes in the following years. The 1870 census possibly places him in the unorganized Dakota territory as a soldier at Fort Sully; there’s an entry that year for a Mark Roach born in Maine around 1846 which may be a match. And then, in 1877, we find the death in Boston of 28-year-old Mark Roach of Lewiston, Maine. At the time of his death he was working as a hatter, and his cause of death was “congestion of heart lungs.” His final resting place is not known.

The Cemetery Vandals – Punishment

The sheriff’s log and newspaper accounts of the 1866 incident state that each boy was fined $300 for the desecration of the cemetery. This seems to be an extraordinary fine. Compare it to the fines imposed for other crimes they subsequently committed: $9 for one case and $5 plus court costs for a second case of assault and battery against Blackenburg in 1867 and 1868, and $5 plus court costs for a case of assault and battery against McGuire and Sullivan in 1867.

The sheriff’s log is more telling, for the entries that come before and after theirs include these crimes and fines for other people:

- Drunkenness and disturbing the peace: $3 fine plus $3.42 court costs

- Assault: $3 fine plus $16.55 prosecution costs

- Drunkenness: $4 plus $3.47 court costs

The theft of the grave rails was not considered by the judge to be in the same class of these more common crimes. Two men who were found guilty of “bastardy” (fathering an illegitimate child) received fines of $300 and $500. Perhaps the judge was intending to send a message to the community that our cemeteries are sacred places and that he would not tolerate their desecration. Perhaps because the victim had been a well-respected member of the town the judge levied the substantial fine. Would he have assessed a fine of this value if the metal railings had encircled a vacant lot at the cemetery? It’s not clear.

Surprisingly, the sheriff’s log recorded that John Blackenburg had “furnished (the) sum.” Where John got this cash is not known, but for a teenage boy this was an extraordinary amount of money. I wonder if he used the money received from the sale of the stolen grave rails; more likely is that his soon to be father-in-law gave him some cash to keep him out of jail and preserve his own (and his daughter’s) standing in the community. It would not have looked good for his son-in-law to be fresh out of jail on his wedding day.

John McGuire, John Sullivan, and Mark Roach did not pay their fines, and served 30 days in jail. With respect to the notion of “lessons learned,” their jail time did not deter McGuire and Sullivan from further trouble, as they ended up back in jail less than a year later. Only Mark Roach—perhaps the least likely of the four—seems to have turned his life around.

The Wrap-up

Today, 150 years after the Portland teenagers vandalized the cemetery, we face similar challenges. We find signs of intentional desecration such as broken stones, stones knocked off their bases, scratches and writing—sometimes even paint—on stone surfaces, and quite recently, graffiti painted on the front gate posts. There are cases of inadvertent damage as well, when the cemetery mowers get too close to markers and scratch, topple, or break them. Thanks to the efforts of our friends-of-the-cemetery group, Spirits Alive, our “Conservation Crew” has worked to clean, straighten, or repair hundreds of gravemarkers. While we cannot always bring a damaged stone back to its original condition, we are winning the battle against the vandals, and Eastern Cemetery is all the better for it.

I thank Cindy Murphy for setting me on this journey, Tiffany Link for helping me make sense of the notes in the sheriff’s log, John Babin for his expertise regarding the Longfellow connection, Larry Glatz for his expertise regarding all things military, and Matt Barker for his expertise regarding the Irish of Portland in the mid-19th century.

Published Sources

Description and PDF version: The Desecration of Judge Potter’s Grave and the Lads Who Committed the Crime

- Babin, John William. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in Portland. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015.

- Barker, Matthew Jude. The Irish of Portland, Maine. Charleston, SC: the History press, 2014.

- Jordan, William B. Jr., Burial Records … of the Eastern Cemetery. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 2009.

- —— Record of Interments with Historical Notes. 1978 manuscript.

- Romano, Ron. Portland’s Historic Eastern Cemetery. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2018.

- Willis, William. A History of the Law, the Courts, and the Lawyers of Maine… Portland, ME: Bailey & Noyes, 1863.

Other Sources

- Ancestry (vital records, census files, family trees…)

- Family Search (genealogy records)

- Find a Grave (gravestones, cemeteries)

- Genealogy Bank (Weekly Eastern Argus, Gazette, and other newspapers from 1820)

- Maine An Encyclopedia (capital punishment in Maine)

- Maine Historical Society collections (sheriff’s records, images)

References

1 The ad notes the cemetery’s location as Westbrook; town lines subsequently changed so that the location was Deering, and later Portland as it is today. Back to text 1

2 See the roster of removals on the Spirits Alive website. Back to text 2

3 See Find a Grave memorial #104237201. Back to text 3

4 A legal recourse allowing a person to report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to the court and to ask the court to order the custodian of the detained or imprisoned person to appear in court, so that the court can determine whether or not the detention or imprisonment is lawful. Back to text 4