The Tombs: A 2017 Update to the 1978 Record of Interments with New Historical Notes

Fourth in a series of Occasional Papers about Eastern Cemetery in Portland, Maine

by Ron Romano

© 2017

In 1978, William B. Jordan, Jr., complied a “Record of Interments with Historical Notes” for Eastern Cemetery. That document contains a sequential (by section, row, & plot) list of about 4,000 burials. Included are the names of 672 people who were buried in the 95 private family tombs at the historic burial ground. But the 1978 list of tomb burials is inexplicably incomplete. This paper provides an update to the Record of Interments, more than doubling the list of entombed from 672 to 1,387, and gives new historical notes about tomb owners, removals to other cemeteries, and more.

Contents

- Introduction

- “Roster” versus “Record”

- Creating the 2017 Update

- Tombs

- Tomb Owners

- Change of Ownership

- Final resting place? (Not so fast...)

- Some Moved In

- Discovering Others Who were Entombed

- Cenotaphs

- Final Miscellany

- Source

- Tables

Introduction

Nine years after compiling the “Record of Interments...” (RoI), Jordan published a book entitled “Burial Records, 1717–1962, of the Eastern Cemetery, Portland, Maine.” The book contains 7000 names, organized alphabetically. The book’s list is nearly double that of the RoI since the book contains all burials known to Jordan at the time—including many who were buried in unmarked graves or have lost their original gravestones due to neglect, vandalism or natural deterioration. Jordan’s sources were primarily the surveys performed by city engineer William Goodwin and cemetery sexton William Hoadley, whose work preceded Jordan’s by 100 years.

The 3,000-record discrepancy between the RoI and book makes sense. The RoI is a sequential list of burials at known plots, so all those people with unmarked graves who are listed in the book are excluded from the RoI.

Still, it became evident to me in 2016 that the RoI’s list of 672 entombments was missing some names. I was preparing a tour for the Portland Observatory’s volunteers to show them the monument at Captain Lemuel Moody’s family tomb, as well as the individual gravestones scattered throughout the burial ground for 40 other members of his family. The RoI lists the Captain and eight others buried in his private tomb, yet when I cross-checked the list with the alphabetical burial records in the book, I found two more Moodys listed for the tomb.

This led me to check records for a few other tombs and the results were the same: the RoI’s list for each tomb I checked was consistently lower than the number of people listed in the book. I then decided to reconcile records for all 95 tombs. Ultimately, I found that the RoI had under-reported tomb burials by more than 50%.

Three tables are included in this paper:

- Table 1: 2017 Revised List of Tomb Owners

This provides new information about the known tomb owners, adds owner names to some tombs that were previously unassigned, and provides the tomb-by-tomb revised number of interments. For example, for Tomb A–30, owned by John D. Hamblet, note that the RoI listed only 2 people, but after reconciling with the burial records in the book, we have a new total of 24 known burials in that tomb. - Table 2: 2017 Revised List of Tomb Burials, by Tomb

This provides the revised list—by tomb number—of 1,387 people known to have been entombed, with many new notes about those who were subsequently moved to other cemeteries. - Table 3: 2017 Revised List of Tomb Burials, Alphabetically

This lists the same 1,387 people found in Table 2, but in alphabetical order versus by tomb number.

“Roster” versus “Record”

Jordan’s original document might better have been titled, “Roster of Current Interments,” since—with only a couple of exceptions—his list excluded names of those known to have been later moved to other cemeteries. To me, the “record” of interments for these tombs should be just that—the list of everyone known to have been buried there, whether temporarily or forever. My Revised List of Tomb Burials includes about 75 people who were moved to other cemeteries. Still, those 75 names account for only 10% of the difference in the number of people entombed on my list compared to Jordan’s. It’s unclear why his roster excluded hundreds of others.

Creating the 2017 Update

My first task was to transcribe Jordan’s list of entombed (detail, Figure 1) to a new spreadsheet, to enable my sorting and studying the data more efficiently. Jordan had organized his RoI with four elements:

- Section & plot number

- Name of interred

- Age or date of birth

- Date of death

Figure 1.

- A Tomb 48—Levi Cutter, 82, 2 March 1856; Lucretia Mitchell Cutter, wife of Levi, 57, 13 April 1827; Elizabeth J. Cutter, 22 m., 8 September 1806; David M. Cutter, 33, 16 December 1831; Julia A. Cutler, wife of Rev. Samuel, 24, 28 December 1830

Note that Jordan preferred using “A Tomb 48” in his work; I use “Tomb A–48” in mine. I organized my spreadsheet with seven elements (See Table 2):

- Tomb number

- Name

- Death year

- Age

- In RoI?

- In Book?

- Notes

| Tomb | Name | Death year | Age | In RoI? | In Book? | Notes (quotes are from burial records found in the book) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A–27 | Stevens, Margaret | 1850 | 89 | - | yes | "Buried Butsey tomb" |

| A–27 | Stevens, Nellie C. | 1874 | 19 | yes | yes | - |

| A–27 | Stevens, Thomas | 1853 | 2 | - | yes | - |

If the name of the entombed person appears in the original version, there is a “yes” in the column labelled In RoI?” If the name of the entombed person appears in the book, there is a “yes” in the column labelled “In Book?” Some names appear in both sources, but others weren’t in either. They came to light as a result of my additional research using external sources such as census data, early directories, vital records of death, and the findagrave.com website. For those, an explanation is found in the “notes” column.

Tombs

Eastern Cemetery holds 95 private family tombs, plus the city receiving tomb (when active, used for winter storage of bodies) just inside the Congress Street gate. Jordan wrote of the tombs “a total of ninety-five were built with all but ten located in four rows along the northern edge of Funeral Lane.” But a closer look at the plot map (Figure 2) and the RoI shows that 86—not 85—tombs are in Section A in the parallel rows along Funeral Lane and 9—not 10—are located in the old section on the southern side of Funeral Lane. Each tomb has a private stairway, about a third of which have an “owner’s marker” at the head of the stairway (Figure 3). Original owner’s markers are mostly sandstone or marble (Figure 4); one newer one is granite. They usually are found inscribed with just a name and date (similar to a footstone found on graves in the open areas of the cemetery).

Figure 2. Detail of Eastern Cemetery plot map showing the majority of the Section A tombs.

Figure 3. Tomb A–46. The large base ledger slab at the rear of the photo rests over the tomb itself. The six columns and top ledger originally present are now missing. The small owner’s marker in the foreground is at the top of the private stairway into the tomb.

Figure 4. Detail of owner’s marker for Tomb A–46.

Tomb Owners

Jordan typically listed known tomb owners first on the RoI’s sequential list, often without ages or dates. Sometimes a date was provided in parentheses just after the name. For example: “J. Kimball (1825)” is listed in the RoI for Tomb A–52; the date is when Kimball took ownership. During my field survey, I found a sandstone owner’s marker inscribed exactly the same. This was true for many tombs in Section A; notes to this effect are found in Table 1. I was able to identify some other tomb owners by searching the external sources named above. In cases where no owner was identified in the RoI or book, I took one of two paths:

- For 16 tombs, I assigned ownership to the predominant family. See Tomb A–59 “Lewis family.” Thirteen people are known to be entombed; since 12 of the 13 are named Lewis, I assigned ownership to that family.

- For 30 tombs, no predominant family was found. See Tomb A–29 “Six families.” Thirty people with six family names are known to be entombed. Until a more exhaustive examination of those thirty is performed to look for familial relationships, I assigned the tomb using “Six families.”

Finally, some burial records named a tomb owner, but no other records were found for other family members or for a specific tomb number. For example: Arthur Mack. Frances Ilsley’s 1842 burial record notes that she was “buried in Arthur Mack’s tomb,” yet no other records are found in the RoI or book for anyone named Mack, and my review of external sources didn’t help. In these cases, the tomb number in Table 1 is “unknown.” There are 15 such listings.

Change of Ownership

Tombs were not always held by the same family. For example, the 1850 burial record for Margaret Stevens reads, “Buried Butsey Tomb” and “A Tomb 27” yet no other records for anyone named Butsey are found at Eastern Cemetery, and the list of 24 entombed in A–27 includes 15 Stevens and 7 Mitchells. While Butsey may have been the original owner, he apparently sold the tomb to the Stevens and Mitchell families at some later point.

Final resting place? (Not so fast...)

The notion of “final resting place” is a misnomer at Eastern Cemetery, for a great number (certainly dozens, and very likely hundreds) were later moved to other cemeteries. This was encouraged by the city in the mid-nineteenth century, when the 6-acre Eastern Cemetery was completely full, and the 240-acre Evergreen Cemetery was opened in the adjoining town of Deering (later annexed to Portland). Though some people were disinterred from the open ground of Eastern Cemetery, removals occurred far more frequently from the entombed population, and this makes sense. The private family tombs at Eastern Cemetery were primarily out of reach of the ordinary citizen; the well-to-do owned them. For its long history, Eastern Cemetery has truly served as a utilitarian burial ground, so when the beautifully-designed Evergreen “garden” cemetery opened in the 1850s, affluent families bought plots, and systematically moved relatives from their Eastern Cemetery tombs to their new final resting places at Evergreen.

Tomb A–37 was assigned to “Owen” in the RoI but Jordan noted that “Bodies moved to Evergreen Cemetery Nov. 1890” and he had nobody listed in the RoI for that tomb. Removals did not always involve the complete emptying of a tomb. Tomb F–96 holds many members of the Fox family, yet only two were later moved out. John (d. 1852) and his daughter Lucy (d. 1854) were reburied at Evergreen. This most likely happened when John’s wife (Lucy’s mother) died in 1875. Her vital record places her at Evergreen, not Eastern, and so her late husband and daughter probably joined her at Evergreen upon her burial there.

Tomb A–82 is assigned to seven families. Twenty-two records of entombment exist, but the three people named Osgood were later moved out, and their bodies went in two directions. Mary Fogg Osgood (d. 1841) ended up at Evergreen Cemetery, while Cornelia and Georgetta Osgood (both d. 1849) ended up at Mt. Pleasant in South Portland. The Osgood case suggests that the Osgood family gave up their share of the tomb, since they seem to be the only three who were moved to other cemeteries.

I have so far found records of bodies moved out of at least 24 tombs, with destinations of Evergreen and Western Cemeteries in Portland, Calvary and Mt. Pleasant in South Portland, and Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Details of these removals are found in Table 2.

Some Moved In

There are three people named Hersey in Jordan’s book. The first is Elias, who died in 1837 at age 49 and was entombed in A–31; he is also found in the RoI. The others, Frederick, age 19, and Harriet C. Hersey, age 14, are also found in the book as entombed in A–31, but not listed in the RoI. The burial note for the teenagers reads “Removed from Bangor...” A check of Portland vital records shows matching dates of death for Frederick and “H. C.”, April 20, 1864. This is most likely the date the two were removed from Bangor and entombed at Eastern Cemetery. Both vital records note them to be male and to have a father named Joshua Hersey (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Portland vital record for Frederick Hersey. The record for his sister Harriet uses the identical date, suggesting that the two were moved on April 20, 1864 versus died on that date.

Joshua was married in Portland in 1839 and appears in the 1850 and 1860 censuses for Bangor. Perhaps Joshua and Elias were brothers? Birth years are within six years of one another and both seem to have ties to Portland and Bangor. Vital records aren’t found for actual death dates for Frederick or Harriet, although the assumption is they died in Bangor between 1860 and 1864. Both appear in the 1850 and 1860 census records. Frederick is 5 in the 1850 and 15 in the 1860 file, while Harriet is 0 in the 1850 and 10 in the 1860 file. The Portland vital record used only “H. C.” (I discovered she was Harriet) and incorrectly listed her as a male. No death record was found for their father Joshua, who lived to at least 1860.

Despite the lack of a complete paper trail, this case provides a good example of a family who moved bodies into a tomb, as opposed to the far more common removal from a tomb.

Discovering Others Who were Entombed

Margaret A. Knapp’s burial note reads “Buried James Crie tomb.” No tomb number was assigned to him. James Rennie Crie was born 1809, died 1883 and was buried at Evergreen Cemetery with his second wife, Lucy Stevens Crie (also d. 1883). He was a shoe merchant, and from his first marriage to Julia Chandler (1809–1846) six children were born. Three died in infancy; Julia joined them in the Crie tomb at Eastern Cemetery in 1846. James Henry Crie, her first child, was born 1833 and lived to 1868. He was entombed with his mother and 3 siblings, but the five of them were moved to Evergreen on August 30, 1868. The record of removal reads, “James Crie, wife, & 3 children of” were removed from the “East Yard” to Evergreen Cemetery. This is misleading, since tomb owner James Crie was still alive, appearing in the 1870 census. So the James Crie on the 1868 removal record was actually his son, James Henry (1833–1868). The five Cries (Julia and the four children) were never included in Jordan’s publications, but are now listed in mine.

Cenotaphs

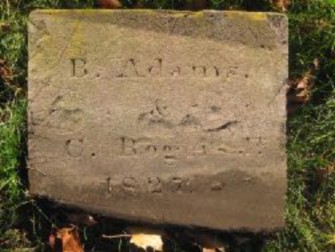

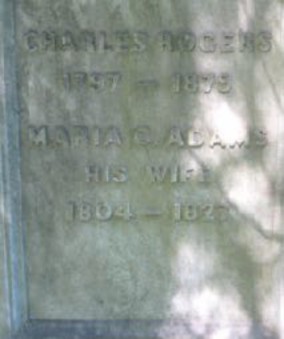

Cenotaphs present a special challenge. Many families erected a family monument after the death of the patriarch of the family; these large monuments often name family members who predeceased him but who may not actually be buried at the site of the monument. Maria C. (Adams) Rogers provides our example (Figure 6). She died in 1827 at age 23 and was buried in her family’s tomb at Eastern Cemetery. Her husband Charles Rogers remarried twice and lived a good long life. When he died in 1879 at age 82, a monument was erected at Evergreen Cemetery. Found on the monument are the names of all three wives. The first panel is shown in Figure 6, a second panel names Charles’ second and third wives. The plot map held by the cemetery office does not include the assignment of a grave for Maria. So while it is unlikely that Charles had Maria’s remains removed to Evergreen Cemetery 52 years after her death, the inclusion of her name on the monument might lead some to think she is buried there.

Figure 6.

Final Miscellany

- Tomb A–24: This tomb was owned by the Second Parish Church.

- Tomb A–26: This tomb holds the last known burial at Eastern Cemetery, that of Harry Blake in 1962. He was 78.

- Tomb A–62: This tomb holds the only person of color known to be entombed: Ann Maria Lambert, who died of consumption at the age of 29 in 1847. (All others were buried in the two African American burial patches.)

- Tomb A–80: This tomb was first owned by John Mussey, who was moved to Evergreen in 1871 (Figure 7). It’s now called the Jordan tomb. Bill Jordan, author of the original RoI and book, had noted he wanted to be buried in this tomb, but upon his death in 2015, he was buried elsewhere.

- Tomb A–84: This tomb was owned by the First Parish Church.

Figure 7.

Source

Description and PDF version: The Tombs: A 2017 Update to the 1978 “Record of Interments” with New Historical Notes

Tables

View and sort the tables on their own pages: