Empty Graves, A Roster of Cenotaphs at Eastern Cemetery

Eleventh in a series of Occasional Papers about Eastern Cemetery in Portland, Maine

by Ron Romano

© 2023

(Photo by Nancy Moore)

In the spring of 2023, military historian Larry Glatz asked if I had a list of cenotaphs at Eastern Cemetery. He had found records for a dozen “empty graves” while doing research on other matters, most of which were references to young men whose burial records noted that they’d been lost at sea. He also knew of stones at Eastern Cemetery honoring service men who’d been buried where they had fallen in battle (or died of disease). Having spent years analyzing the burial records for Eastern Cemetery and creating rosters on a variety of topics, I decided to take a deep dive and create a list of cenotaphs. As is always the case, I found that the stories that emerged from Eastern Cemetery’s interred range from tragic to fascinating to simply bizarre. This paper tells some of those untold stories and shines a spotlight on an interesting category of cemetery stone—the cenotaph.

Contents

- A Cenotaph is...

- The Research

- Sorting the Findings

- Making Judgement Calls

- Lost at Sea

- Died at Sea

- The Dash (and the Dart)

- Died Abroad

- Epitaphs

- Cenotaphs within the Cemetery

- 3 Honorable Mention Cenotaphs

- Final Thoughts

- Appendix A - Cenotaphs Plot Map

- Appendix B - Transcription Form (2 pages)

- Table A - Intentional Cenotaphs

- Table B - Unintentional Cenotaphs

- Appendix C - The Only Survivor of the Wreck

- References & Sources

A Cenotaph is...

A cenotaph is a monument that memorializes someone who is buried elsewhere. Pronounced “SEN uh taff,” it’s a word rooted in the Greek language meaning “empty tomb.”

The Research

The first casting of the net – Jordan’s book

To find Eastern Cemetery’s cenotaphs, I wanted to cast as wide a net as possible. While we know of about 7,000 records of burials, they come from different sources. I started with Bill Jordan’s book “Burial Records... of Eastern Cemetery.” This is an alphabetical listing of those Jordan knew to be memorialized at the cemetery as of 1987 (but not published until 2009). He’d used vital records and surveyed the cemetery in order to create the book, and it serves as a good starting point for this kind of research. Going page by page, I looked for references such as “lost at sea” or “died at” a faraway place. Jordan’s book can be very helpful, but it has also been found to be full of errors and omissions. His work was done before the availability of the internet and digitized records, so it is wise to verify entries with other sources. About half of the 106 entries on the new cenotaphs roster were found in this first casting of the net.

The second casting of the net – the Record of Interments

I then looked at the “Record of Interments...,” also by Jordan. He completed that document in 1978, about a decade before the list used in the book. Not alphabetical, this 145-page list instead organizes names by location (starting with Section A, Row 1, Grave 1 and ending with Section L, Grave 90). As above, I went page by page looking for references that might suggest a person was not actually buried at the cemetery. In some cases Jordan included burial notes, but all of those were also covered in his book. This was a less successful effort, as no new entries were found for the cenotaphs roster.

The third casting of the net – Veterans

I next reviewed the list of Veterans memorialized at Eastern Cemetery. Each year, volunteers from the cemetery’s friends group, Spirits Alive, decorate the plots of those who served the country. Veterans of the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the Civil War are most common. That roster exceeds 225 names. For this paper, I focused on those veterans whose death dates occurred within the period of their service. In other words, a War of 1812 veteran who died in 1813 was researched to see if he died away from home (with burial where he fell). But a War of 1812 veteran who died in 1840 was not further researched, since it’s more likely than not he was buried at Eastern Cemetery. Some of these entries overlapped those already found in the first casting. Nevertheless, this effort resulted in about 10% of the entries found on the cenotaphs roster.

The fourth casting of the net – Removals

By the mid-1800s Eastern Cemetery had fallen out of favor. Portland families preferred Evergreen Cemetery, the new “garden” cemetery in nearby Deering (annexed to Portland at the end of the century). Evergreen offered a beautiful landscape that took advantage of its natural hills, native trees, and water features. Perfect for picnicking and strolling (oh yes, and mourning too...), it quickly became the most popular place to bury one’s dead.

Encouraged by the city to do so, families had bodies removed from Eastern and reburied at Evergreen. I created the roster of known removals from Eastern in 2020 and continue to update it as more are discovered.1 It reflects that there was indeed a mass migration of human remains from the city’s oldest burying ground, as it contains the names of 700 people—550 of whom ended up at Evergreen.

Figure 1. Monument for John Mussey

In most cases, when remains were removed from Eastern Cemetery, the gravemarker on the plot was also removed (see John Mussey’s stone at Evergreen above (Figure 1). But in some cases, markers were left behind. This usually occurred within the section where 86 underground family tombs are found. Many of the tombs were shared by families, since up to thirty people could be entombed together in the largest ones. For example, the pedestal monument over Tomb A - 14 has twenty inscribed names, from the Williams, Libby, and Nichols families. The four Libbys were later disinterred and reburied at Evergreen Cemetery, but the monument was left standing at the tomb because the Williams and Nichols families were not removed. This then serves as a cenotaph for the four members of the Libby family.

For this phase of research, I searched the “moved” roster for names of those who have two memorials—one at Eastern and another where they were reburied. This effort resulted in about 15% of the entries on the new cenotaphs roster. When markers are found at Eastern and another cemetery, my working assumption is that the Eastern Cemetery marker is the cenotaph, since we know that hundreds of people were removed. However, there may be cases in which families did not remove bodies from Eastern Cemetery but instead decorated their Evergreen lots with stones for all of their family members regardless of their original interment site. When two monuments are found, clearly one of them is a cenotaph!

While there is a good deal of space at Eastern Cemetery that appears to be unoccupied (for lack of any markers), we believe that remains would most likely be found if we were to dig for them. The cemetery was established in 1668. No records were maintained (or have survived) for its first 150 years, and given that the landscape was the subject of a great deal of vandalism and neglect for its second 150 years, it’s impossible to know the true number of those who are under the ground in unmarked graves. The first survey of the cemetery wasn’t even conducted until 1890—long after the city had “closed” the cemetery to new burials2 and the mass migration of 700+ had occurred. At the time of that survey, the city engineer marked each known grave with a small round concrete “plug” (shown for plot C - 90) (Figure 2) and created the plot maps we still use today.

Figure 2. Plot marker (Photo by H. Doggett)

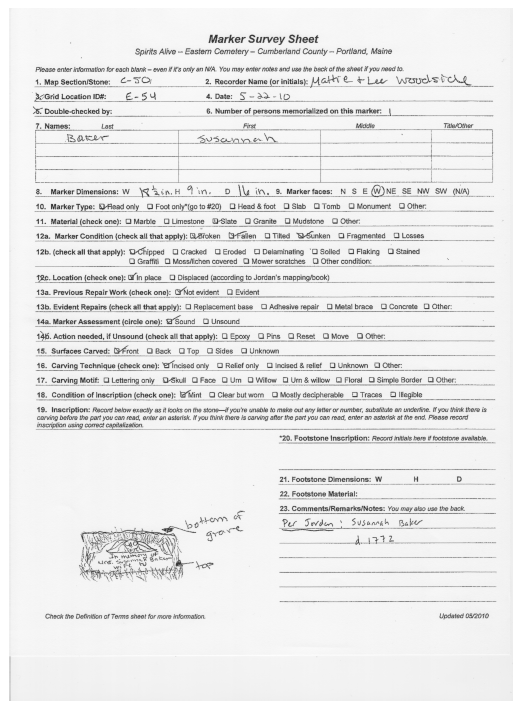

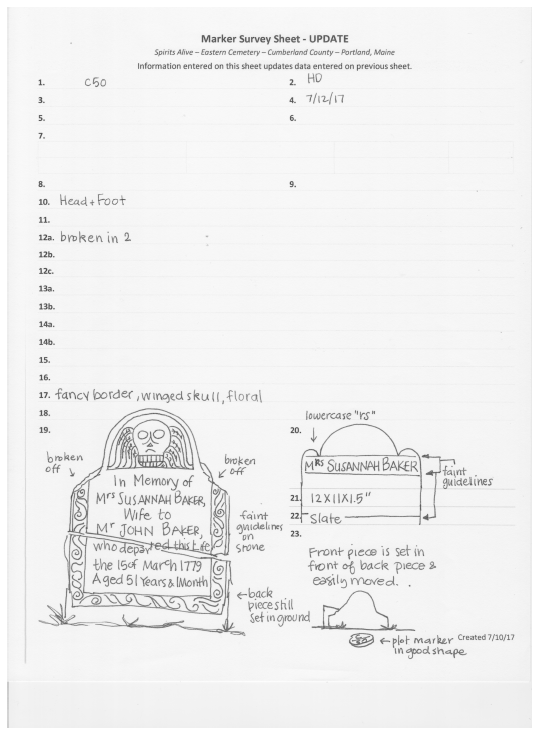

The fifth (and final) casting of the net – Transcriptions

Arguably the most successful effort came from the Spirits Alive Transcription Project. Over the course of many years, volunteers under the direction of longtime board members Martha Zimicki and Holly Doggett have painstakingly recorded exactly what is found on each of the marked and mapped plots from the 1890 survey. A form is completed for each marked grave site which documents the size, material, and condition of what is found there, if anything.

Included on many of these forms are hand-drawn renderings of the stone or remnants, and a transcription of what is readable on the marker. In most cases I found these forms to be more helpful than the gravestone photographs posted on findagrave.com.3 The transcription team is often successful in teasing out letters from some eroding surfaces that front-on photographs just cannot accomplish. As well, a photograph captures only what we see from the sod-line up; the transcription team sometimes digs away the sod in order to record the inscriptions and epitaphs hidden from view by the grass. About 25% of the people listed on the new cenotaphs roster resulted from this work. Overall, the transcription forms ended up being the richest source for this research; had I cast this as the first net, I would have captured the vast majority of the 106 names now on the cenotaphs roster.

Sorting the Findings

As I built the list of 106 cenotaphs, I was fully researching each case by verifying them with primary sources such as vital records, published family genealogies, newspaper notices of death, and listings on findagrave.com. Through all of this, some trends were noticed and it became clear to me that cenotaphs can be separated into buckets. It led to my creating three categories explained below, but to summarize: Cenotaphs and Secondary Cenotaphs are both considered to be intentional memorials, while Unintentional Cenotaphs are not. Each of the 106 that made it onto the list are found in the roster at the end of this paper and are assigned to one of the three categories.

The first category is:

Cenotaph: A marker placed specifically to memorize a person who is not buried there.

Figure 3. Gravestone for William Knight

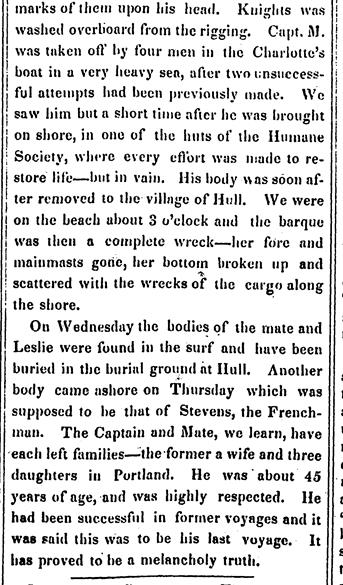

In most cases we find there to be a single stone memorializing one person. For example, an eroding white marble stone is found in Section A, Row 2, Grave 11 for Capt. William W. Knight. On either side of him are three other markers for the Knight family. Though challenging, the inscription on the captain’s stone can still be read; the epitaph of eight or more lines, however, has eroded away.4 It’s evident that this stone memorializes only the captain, since the marker’s inscription reads:

Capt. WILLIAM W.

son of

Capt. Benj. & Mary Knight

Drowned March 31, 1832 on his passage from

Portland to Havana,

aged 24

Because his death occurred on the way to Cuba, it is clear that he would have been buried at sea, making this stone a true cenotaph.

Twenty-five percent of the cenotaphs at Eastern Cemetery are of this type.

Secondary Cenotaph: A marker placed primarily on someone else’s grave, but which also memorializes a relative who is not buried there.

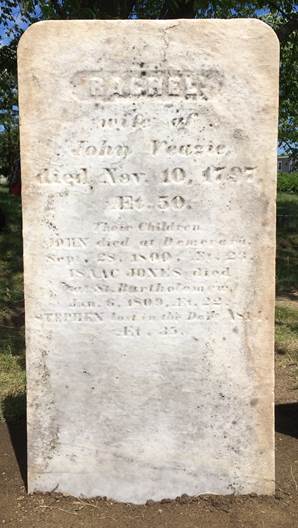

Figure 4. Gravestone for Rachel Veazie (Photo by Diane Brakeley)

Eastern Cemetery has a good number of these; nearly sixty percent of all cenotaphs are secondary ones. A tall white marble marker, recovered from the ground, cleaned, and set back upright by the Spirits Alive conservation team in 2018 memorializes Rachel Veazie and three of her sons. She was the wife of John Veazie, who died in 1806, almost ten years after Rachel, and has his own marker at J - 107, the plot next to Rachel’s (J - 108). The inscription is clear on this marker:

RACHEL

wife of John Veazie

died Nov. 10, 1797

AEt. 50.

Their Children

JOHN died at Demarara,

Septs. 28, 1800, AEt 23.

ISAAC JONES died

at St. Bartholomew

Jan. 6, 1809, AEt 22.

STEPHEN lost in the Dash 1814

AEt. 355

Both Rachel and John’s markers are of a size, shape and lettering typical of the gravestones produced in the mid-1800s, not 1797 or 1806, so they were placed in the cemetery long after their deaths.

Rachel’s stone serves both as her true gravemarker as well as a secondary cenotaph for her three sons, as they all died and were buried abroad. John’s death in Demarara (a region of Guyana on the north coast of South America) was confirmed in a newspaper at the time. Isaac’s death was also confirmed in a newspaper. St. Bartholomew is today familiarly called St. Barth’s, or St. Barthelemy, a Caribbean island of the West Indies.

Stephen’s death is perhaps the most noteworthy, as he died in the wreck of the well-known privateer schooner Dash.

The plot map of the cemetery provides one more clue to the secondary cenotaph entries. In the case of another Rachel Veazie—this time Rachel (Veazie) Shaw—and her two husbands, she was buried at plot J - 106 when she died in 1849 at age 79 (Figure 5). Her plot is a single one, immediately beside John Veazie’s. There is simply no room for her husband to have been buried with her, and the fact that she so far outlived them both (first husband Thomas Hilton died 1793 and second husband Samuel Shaw died 1818) further confirms that the stone is her gravemarker and a cenotaph for her husbands.

Figure 5. Gravestone for Rachel Shaw (Photo by Diane Brakeley)

- RACHEL SHAW DIED Oct. 16, 1849 AEt. 79, Husband of the deceased: THOMAS HILTON died Dec. 1793, SAMUEL SHAW was lost at sea June 1818

Figure 6 (Photo by Nancy Moore)

In most secondary cenotaphs, the people who were actually buried at the cemetery are listed first on the stone, as we saw with both Rachel Veazie and Rachel Veazie Shaw. Those not buried with them are inscribed below them in secondary positions. But the Weeks family marker that’s found at plot D - 146 differs. As shown above, the top of the marker reads:

Erected to the memory of

CAPT. JOSEPH WEEKS,

died, on his passage from the W. Indies,

July 1797. AEt. 35

Below this we find:

DANIEL, son of Capt. Joseph &

Mrs. Lois Weeks, lost on board

Brig Dash 1815. AEt. 27

In the third position:

LOIS widow of Capt. Joseph

Weeks, died Jan. 26, 1829

AEt. 69

It was Lois’s death that prompted the family to purchase this gravestone, and she is the only one of the three to actually be buried in this plot, yet she got third position on the marker. The design of this stone is of the period of markers being produced at the time of her death, not her husband’s, so this is not a case of a marker being made in 1797 and names being added over time. It’s a subtle, but interesting, difference from most of the other secondary cenotaphs found.

Unintentional Cenotaph: A marker placed on a person’s grave that was left behind when the deceased was disinterred and reburied elsewhere.

This is the third category of cenotaph. The monument at Tomb A - 14 addressed above for the Williams - Libby - Nichols families provides the example. Fourteen monuments of this type are found at Eastern Cemetery, naming 21 people. In the following analyses, these people (and monuments) are excluded, leaving us with a population of 86 people.

Making Judgement Calls

I made some judgement calls during the search for cenotaphs at Eastern Cemetery. One relates to the year of death. Since embalming was not in common practice until the Civil War era, most deaths abroad that occurred before the war would have resulted in burials where those people fell. It would not have been easy—or practical—to transport a decomposing body home from the Caribbean in the early 1800s. But for mid-century deaths abroad, this became a better possibility.

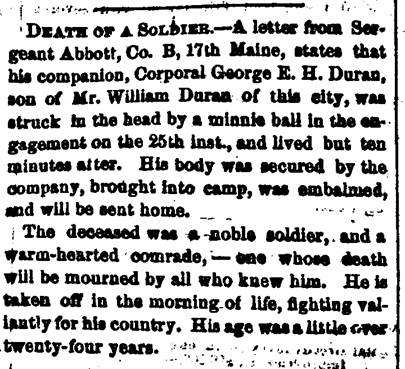

A modern granite marker from the Veterans Administration is found in Section A, at Tomb 40 for George E. H. Duran, who died in battle in Virginia during the Civil War. A newspaper clipping confirms that the stone is an actual gravemarker and not a cenotaph.

Figure 7. Grave marker for George Duran (Photo by Janice Gower)

- George E.H. Duran, CO B 17 MAINE INF, CIVIL WAR, 1841 1865

Figure 8

- DEATH OF A SOLDIER - A letter from Sergeant Abbott, Co. B, 17th Maine, states that his companion, Corporal George E. H. Duran, son of Mr. William Duran of this city, was struck in the head by a minnie ball in the engagement on the 25th inst., and lived by ten minutes after. His body was secured by the company, brought into camp, was embalmed, and will be sent home.

The deceased was a noble soldier, and a warm-hearted comrade, — one whose death will be mourned by all who knew him. He is taken off in the morning of life, fighting valiantly for his country. His age was a little over twenty-four years.

Another consideration is distance from home. There are many records at Eastern Cemetery for people who died in Boston. Packet ships—medium-sized ships carrying mail, passengers and goods—ran between the two cities daily for decades and there would have been few barriers to transporting a body from Boston to Portland for burial. None of the listings on the cenotaphs roster are for Portlanders who died in Boston, but there are a handful of listings for people who died relatively near Portland, including Belfast, Maine, and Lynnfield, Massachusetts. There are also cenotaphs for deaths that occurred farther away—including Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, New Mexico, and Washington state, among others.

Figure 9. Hope family gravestone

A small slate marker found at plot I - 25 memorializes two sons of stonecutter Robert Hope and his wife Ann. Hope was an experienced stonecutter when he joined the shop of Bartlett Adams in 1806. He and Ann stayed in Portland just two years. Their son William died in Portland in 1806. Hope carved the slate for his son, but added another son to the inscription, which reads:

In

MEMORY OF

TWO CHILDREN,

THE OFFSPRING OF

ROBT. & ANN HOPE.

both died in infancy:

the former

ROBT. A. HOPE,

died in Virginia 1802.

the latter

WILLIAM I. HOPE,

died in Portland 1806.

There’s a socio-economic angle here as well. Perhaps the more well-to-do families of Portland would wish to cover the costs to preserve a body (such as that of the owner/captain of a trade vessel) for return to Maine; less likely would this be expected in the case of a working class family who lost a son working as a ship’s crewman.

Two small slates, side by side at plots D - 46 and D - 47, memorialize Benjamin (Sr.) and Benjamin Franklin Thrasher (Jr.), both of whom died in Havana. The father died first at age 64 in 1855. Five years later his 40-year-old son followed. A family genealogy notes that members of the Thrasher family relocated to Cuba for a few decades in the first half of the 1800s. A check of the 1830, 1840, and 1850 census records for Portland seem to bear this out, as they do not include Benjamin Thrasher as the head of household in the city. Given the period during which they died, it’s not out of the question that the Thrasher family would have had the bodies of these two men preserved and returned to Portland. But since the family had established a home in Cuba, it seems most likely that they were laid to rest there and their family back home in Maine memorialized them with the small slate markers found today.

Figure 10. Thrasher gravestone detail (Photo by Janet Joyce)

Taking everything into consideration, when it seemed to me to be more likely than not that we have a cenotaph at Eastern for a person known to have died abroad, I included them.

Lost at Sea

It should come as no surprise to those who know Portland’s history that the majority of cenotaphs at Eastern Cemetery are related to its bustling maritime economy of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Seventy-five percent of the intentional cenotaphs at Eastern Cemetery are tied to the sea. All of those are for males, the vast majority of them being in their teens (12 of them) and twenties (36 of them). Four men died in their thirties, seven in their forties, and four died in their fifties to seventies.

There are twenty records of men who were “lost at sea,” “lost overboard,” “drowned at sea,” or “buried at sea.” These are the men whose bodies were never recovered. In some cases the newspapers of the day tell their stories, while in other cases their memorial stones were inscribed with those words.

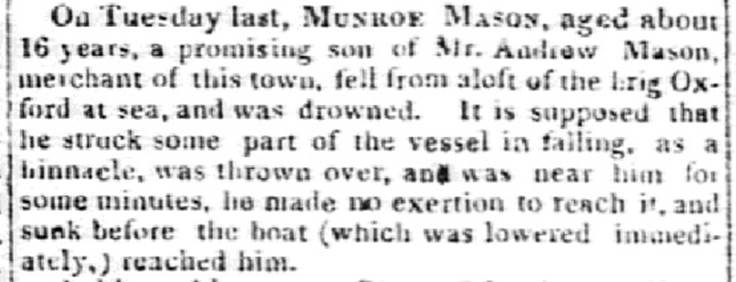

Figure 11. Gravestone for Munroe Mason

Munroe Mason is memorialized on a large white marble stone in Section A, Row 1, Plot 5. Today the stone is too eroded to read (Figure 11), but it appears to have had a lengthy inscription. Whether it contained family relationships, the story of his death, or an epitaph is not known. The newspaper told his story best (shown below).

Figure 12

- On Tuesday last, MUNROE MASON, aged about 16 years, a promising son of Mr. Andrew Mason, merchant of this town, fell from aloft of the brig Oxford at sea, and was drowned. It is supposed that he struck some part of the vessel in falling, as a binnacle, was thrown over, and was near him for some minutes. He made no exertion to reach it, and sunk before the boat (which was lowered immediately,) reached him.

The tall slate gravemarker on plot C - 94 is an example of an inscribed cause of death. The stone was placed on the grave of Mary Sheafe, who died in 1831 at age 55. Her husband’s stone is next to hers; he was William Sheafe who died in 1844. At the bottom of Mary’s marker we find inscribed, “Also their son... lost from the brig Alna on the Florida coast.” John was 29 when he was swept overboard during a hurricane off the south Florida coast in 1838. The Alna was run on to the beach. The survivors were attacked by the natives, who killed the captain and cook and then pursued two other Portland men who fled from the scene. Over a few days, all the while eluding the natives, they had to contend with intense heat, sunburn, alligators, sharks, and mosquitos. They were eventually rescued by another ship and returned to Portland to tell their amazing stories of survival (and confirm John Sheafe’s cause of death)6

Figure 13. Gravestone for Mary Sheafe

- MRS. MARY, wife of William Sheafe, died May 17, 1831. AEt. 55. Also their Son John Sheafe, who was lost from the Brig. Alna, on the Florida Coast, Sept. 7, 1838, AEt. 29.

Died at Sea

There are twenty-six records for men who had “died at sea,” were “lost on board,” or “died during the passage [from one named place to another].” There’s a difference between one who was lost at sea—and certainly went to a watery grave—and one who died aboard the ship while on his voyage. For the latter, there is a possibility the deceased got a land-based burial somewhere, though burials at sea were common. The use of “lost at sea” and “died at sea” was not found to be consistent on gravestone inscriptions, vital records, and newspaper notices. Some who were truly lost at sea were listed as “died at...” and vice-versa, so for the purpose of this paper, I categorized each case as found in the original source documents.

Capt. Benjamin Tappan Chase died in 1821 at the age of 35. There is an eroding, broken marble marker at plot H - 17 to honor him. Jordan’s burial records note that Capt. Chase, “Died of yellow fever on voyage from Cuba.” The assumption is that he was buried at sea, but this case raises the consideration of timing. What if Capt. Chase died one day before the ship reached Portland? In that case, a burial at Eastern Cemetery is a good possibility. But as found, the burial record suggests that he died on the ship farther from home and was buried at sea. Henry Green, Jr., died at sea in 1809. He was 23 and on his passage home aboard the brig Diligence. The stone on plot A - 6 - 10 is inscribed with the words “died on his passage from Havana.” The Portland newspaper that reported his death at sea also included this commentary:

Several of the youths of this town, who promised to become valuable members and ornaments of society, have been destined to perish far from home, within the last two years....

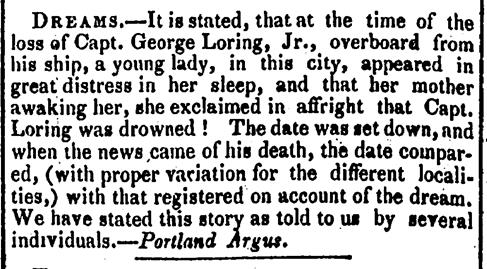

Capt. George Loring gives us a couple of head-scratching moments. His 1847 death at sea is confirmed on a grand white marble obelisk located in Section A of the cemetery, between tombs 83 and 84. The obelisk is set on a granite base and is over six feet tall. Only one panel of the obelisk is inscribed. There we find the captain’s name, date, and age (24) along with “died at sea.” He was one of many children of George and Lucy Loring. George Sr. was a sea captain and ship builder in Portland, and his namesake son had followed in his footsteps. George Jr. became master of the Boston-based ship Eliza Warwick and as reported in the newspaper under the title “Sad Accident at Sea,” he died while on a transatlantic journey to England. With two other men at the ship’s wheel, he was “carried overboard in a tremendous gale.” The heavily damaged ship was able to reach Liverpool, England, without him.

Figure 14. Monument for George Loring

One of the odd things about this case is that George Loring’s monument, shown here and in clear view to all who visit, eluded Jordan as it is not found in either of his published sources. The monument was drawn onto the 1890 survey map, but did not make it onto the city’s record of burials later used to generate listings on the Find a Grave website. It wasn’t until I reviewed the transcription forms that I realized there was a cenotaph present. I’ve since added Loring to findagrave.com.

The most bizarre aspect of this case arose just a couple of weeks after Loring’s death was reported. His death en route to Liverpool was on January 12, 1847, and was first reported in a Boston newspaper on February 22. On March 4, a curious story appeared in the Portland paper that is best told in the words of its writer:

Figure 15

- DREAMS. — It is stated, that at the time of the loss of Capt. George Loring, Jr., overboard from his ship, a young lady, in this city, appeared in great distress in her sleep, and that her mother awaking her, she exclaimed in affright that Capt. Loring was drowned! The date was set down, and when the news came of his death, the date compared, (with proper variation for the different localities,) with that registered on account of the dream. We have stated this story as told us by several individuals. — Portland Argus.

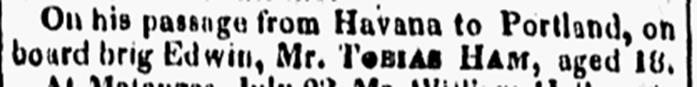

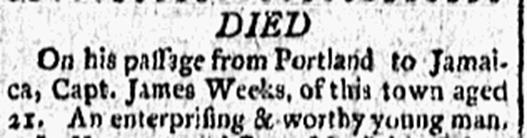

Many of the records for those who died at sea include the ship name, ports of departure, and destination port. It’s easy to come to a conclusion that a death aboard a ship that had left Portland resulted in a burial at sea or in another port (and, therefore, a cenotaph back home). It’s not quite as clear when the ship was on its way back to Portland. An example of each follows:

Figure 16

- On his passage from Havana to Portland, on board brig Edwin, Mr. Tobias Ham, aged 18

Figure 17

- DIED, on his passage from Portland to Jamaica, Capt. James Weeks, of this town aged 21. An enterprising & worthy young man.

The memorial for George P. Richards is found in Section A, Row 16, Plot 6. It’s a white marble restored by the Spirits Alive conservation crew.

Figure 18. Gravestone for George Richards (Photo by Diane Brakeley)

- George P. Richards, Died at sea July 31, 1849. AEt. 17 yrs. & 9 mos., Sarah Richards, Died April 1, 1850, Aet. 14 yrs, 8 mos. (epitaph illegible)

The inscription under George’s name is clear: “died at sea July 31, 1849.” He was 17 when he died. He shares this marker with his sister Sarah Richards, who died less than a year later at age 14. Their father had predeceased them by about a dozen years and their mother remarried and moved to Boston.

This marble may be a true gravemarker for Sarah and a cenotaph for George. The decoration is what sets this apart from other cenotaphs at Eastern Cemetery, as it features a small tree or shrub with two broken buds which are on the ground at the base of the tree. Broken flower buds and broken branches were often carved onto gravestones in the mid-nineteenth century, representing a life cut short. That message is clear on this stone, as it memorializes two young lives lost before the prime of their lives.

The Dash (and the Dart)

We can’t ignore the fact that four of the twenty records for those who were lost at sea name the same vessel—the privateer schooner Dash. During the War of 1812 many privately owned ships were commissioned to engage in warfare at sea. They were, in effect, pirate ships with permission by the US government to seize British ships and crews and steal their cargo for their own use or sale.

The Dash was launched in 1813 in Freeport by the Porter family. Samuel and Seward Porter were merchants in Portland. The Dash was under the command of two other captains before their younger brother John Porter became her captain in 1814. The newly-married young captain, just 24, more than proved his worthiness, as the Dash is generally considered to have been among the most—if not the most— successful privateers during the war. Newspapers up and down the east coast of the US reported Capt. John’s return to Portland on January 5, 1815, after a voyage of seven to eight weeks’ duration. The bounty list is staggering, with the value of goods seized estimated to be about $1,000,000 today. The article is shown here.

Figure 19.

- MARINE NEWS

Portland, Jan. 5

“Privateer brig Dash, John Porter, commander, arrived here this afternoon, after a cruise of seven or eight weeks, and has made five captures, viz: —a schr. with fish, (arrived at Boston some time since;) sloop Mary, bound to Bermuda; with an assorted cargo; brig General Maitland, bound from Martinique to Bermuda, cargo sugar and rum; letter-of-marque schr. Armistice, Capt. Stanhope, of New York, laden with rice and cotton, which she captured; and a brig of George’s bank a few days ago.

“The Dash laded herself from the above vessels with 115 puncheons of rum,

English dry goods, copper in sheets, porter, wine, &c.—Value on board estimated at from $40,000 to $50,000.

“She has captured this cruize, property estimated per invoices at $120,000.

“The General Maitland, and Armistice were manned and ordered for Portland, the latter about 10 days since, off the Capes of the Delaware.

“She has brought in no prisoners, has had no engagement, and been chased but once.

“It is reported that a prize of English goods is in at Wiscasset, and another at Thomaston. At any rate we are in a fair or foul way to have a plenty of dry goods. Sales of a quantity here to day amount to about $100,000—sold at reduced prices—many articles below sterling cost, and such as are precisely adapted to our market.

“P.S. A brig is below, supposed the Dash’s prize, just come in.”

A letter to the owner now in this town states, that the Dash has 115 puncheons rum, 10 hhds. and 45 bbls. sugar, 5 trunks copper plates, 7 casks porter, wine, white lead, &c.

Yours, &c.

E. C. H. B.

Boston, January 7

The Dash was in port for just a couple of weeks. News of the treaty that had been signed by the US and Great Britain— effectively ending the war—had not yet reached Portland, and on January 21, 1815, Capt. John Porter set sail again. Within a couple of days, while in the vicinity of the Georges Shoals (east of Cape Cod), a fierce storm arose. Another privateer chasing the Dash turned back to the safety of land, but saw Porter sail directly into the gale. He was perhaps overconfident in his (and the ship’s) ability to weather the storm that would last for a week. Perhaps he hoped to continue his string of successes on the high seas. But nobody ever heard from him or the Dash again, and all aboard—believed to be 55 in total—went down with the ship.7

The four from the Dash memorialized at Eastern Cemetery are:

- John Mountfort, age 19, on his mother Elizabeth’s stone at plot D - 35

- George Roberts, age 42, ship’s carpenter, on his wife Hannah’s stone at plot A - 13 - 5

- Stephen Veazie,8 age 35, on his mother Rachel’s stone at plot J - 107 (Figure 4)

- Daniel Weeks, age 27, on his parents’ stone at plot D - 146. (Figure 6)

I found records for two other men at Eastern Cemetery who were lost at sea in “January 1815” and I strongly suspect that they were also aboard the Dash when it went down.

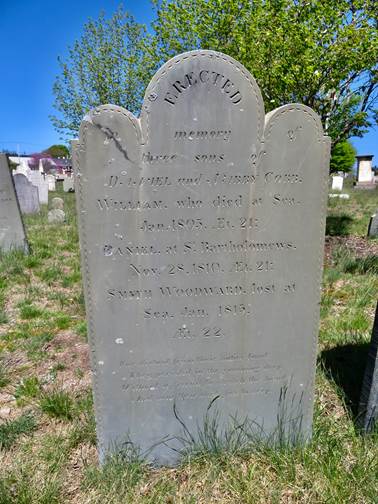

- Smith Woodward Cobb, age 22, on a shared stone with two brothers at plot D - 129 (Figure 20)

- Samuel Shaw, age unknown, on his wife Rachel’s stone at plot H - 35

Though Evergreen Cemetery in Portland would not open for another three decades, there is a cenotaph there for Capt. John Porter. The stone is broken and in the ground, but part of the inscription is still visible, reading “sailed from Portland, January 21, 1815.” Whether this stone was originally at Eastern Cemetery and moved to Evergreen or was only and always at Evergreen has yet to be discovered.

There was another privateer represented at Eastern Cemetery. On the stone for Sally Dodge at plot J - 46, her son Israel’s name is found inscribed with “Lost in the Privateer Dart.” There’s no date of death for Israel, but since the Dart was only active for a few months in 1812, we can assign a death year of 1812 to him.

Figure 20. Gravestone for the Cobb sons

- ERECTED in memory of three sons of Daniel and Nabby Cobb. WILLIAM, who died at Sea, Jan. 1805, AEt. 21; DANIEL, at St. Bartholomews, Nov. 28, 1810, AEt. 21; SMITH WOODWARD, lost at Sea, Jan. 1815, AEt. 22.

Died Abroad

I can tie nineteen more records for men memorialized at Eastern Cemetery to the sea. Rather than finding “lost at sea” or “died at sea” on their records, they instead note that they died in a specific place. The entire Caribbean region dominates, with deaths reported as far south as Brazil, Surinam and Guyana, as far west as Panama and Belize and as far east as the islands of the West Indies. Locations named in these burial records, on stones, and in newspapers include Cuba, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, and St. Barth’s. All of these suggest men traveling from Portland to the Caribbean during the very rich period of trade.

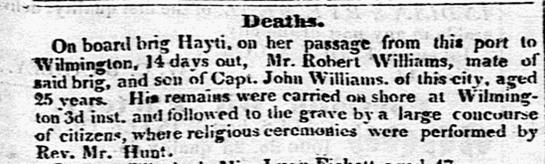

Often, the burial record or the gravemarker does not tell the whole story. Take the case of Capt. Robert Williams who died in February, 1833, at age 25. He is memorialized on the marble pedestal monument at Tomb A - 14, and his inscription reads that he “Died Wilmington, North Carolina.” From this, we might picture him walking around the city and falling victim to a wintertime flu or other communicable disease. But the newspaper provides the details. He actually died at sea while aboard the brig Hayti. The paper reported that his body had been brought to shore, and was “followed to the grave by a large concourse of citizens.” No gravemarker is known to exist for him there, so perhaps he was buried there in an unmarked grave.”

Figure 21

- Deaths. On board brig Hayti, on her passage from this port to Wilmington, 14 days out, Mr. Robert Williams, mate of said brig, and son of Capt. John Williams, of this city, aged 25 years. His remains were carried on shore at Wilmington 3d inst. and followed to the grave by a large concourse of citizens, where religious ceremonies were performed by Rev. Mr. Hunt.

We have one well-known person memorialized on an Eastern Cemetery cenotaph who was buried in the Mediterranean region. Lieutenant Henry Wadsworth, at age 20, died in Tripoli (Libya) in 1804 during the Barbary Wars. He was a crewman on the Intrepid, and on a mission to destroy the flotilla of pirate ships in Tripoli’s harbor. His small boat, loaded with explosives, accidentally blew up before they could accomplish their mission, killing Wadsworth and 12 other men aboard. There’s a memorial of some type in Tripoli for these men who perished over 4,000 miles from home. The large pedestal monument shown here at plot H - 13 in Eastern Cemetery was erected by his grandfather. Having been vandalized many years ago and left in pieces, it was restored by the Spirits Alive conservation crew in 2013. And of course, one of Portland’s favorite sons—the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow—was born in 1807 and named in honor of his fallen uncle.

Figure 22. Monument for Henry Wadsworth (Photo by Dave Smith)

The person memorialized on a cenotaph who was buried farthest from home is another young man named Henry: Henry Tukey. He died in the Dutch East India port of Batavia (today’s Jakarta, Indonesia), nearly 10,000 miles from Portland. The small slate marker at plot G - 33 understates his place of honor as the person who died farthest from home. The stone was placed after the death of his father in 1826. After his father’s inscription we find:

Also,

his son Henry Tukey,

died in Batavia

Oct. 3, 1821

AEt. 26

Epitaphs

Gravestone inscriptions contain the facts: name, age, dates, and perhaps place of death, but the more poetic epitaphs—when found—may give clues as to where a person was laid to rest.

John Cox was a seaman who died at age 20 in 1785. His marker at plot E - 60 is not a cenotaph, but a true grave marker, as confirmed by his epitaph:

Boreas’ winds & various seas

Have toss’d me to & fro,

In Spite of both, by God’s decree,

I harbor here below

Figure 23

“Boreas” is the personification of the north winds, (Figure 23). There’s a second verse to this epitaph, but the point is made in the first verse... that John successfully made his way through his brief career as a seaman by avoiding being swept overboard or lost in a wreck. So congratulations to John for avoiding the watery grave. But still, he died at age 20! His was far too short of a life, and though he probably died of a communicable disease, the truth is not known but for the fact that he was buried at Eastern Cemetery.

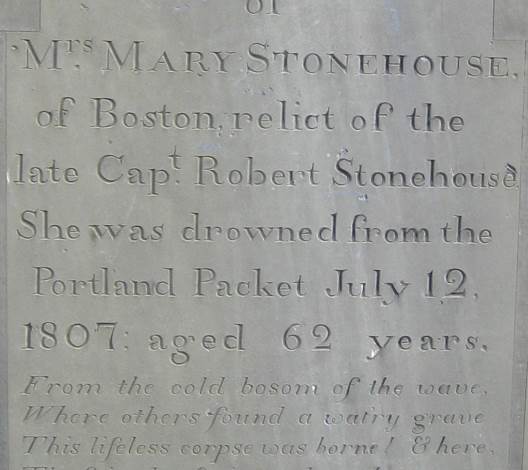

Figure 24. Detail of gravestone for Mary Stonehouse

- Mrs. MARY STONEHOUSE, of Boston, relict of the late Capt. Robert Stonehouse. She was drowned from the Portland Packet July 12, 1807: aged 62 years.

Similarly we have Mary Stonehouse, who was drowned off Cape Elizabeth in 1807. She, her daughter, and grandson were among the 16 who died when a packet ship heading home from Boston fell short. Only seven bodies were recovered; the rest were lost at sea. The three generations are memorialized on two stones placed side by side at Eastern Cemetery.9 Mrs. Stonehouse’s inscription reads in part, “She was drowned from the Portland Packet, July 12, 1807, aged 62 years.” That alone does not tell if she was lost at sea or washed ashore. But the first three lines of her unusually long epitaph confirm what happened:

From the cold bosom of the wave,

Where others found a watr’y grave

This lifeless corpse was bourne!

So she (along with her daughter and grandson) was recovered and buried at Eastern.

Contrast the Cox and Stonehouse gravemarkers with the cenotaph for three sons of Daniel and Nabby Cobb at plot D - 129 (Figure 20). John died at sea in 1805 (age 21), William died at St. Bartholomews in 1810 (age 21), and Smith W. was lost at sea in 1815 (age 22). The epitaph on this stone reads:

Far distant from their native land They perished in the yawning deep Without a friend to stretch the hand And none their early fate to weep.

Likewise, Daniel Moody’s cenotaph, found at plot G - 10, confirms he was not buried at Eastern Cemetery. His inscription states that he died at Havana in 1821 at the age of 21. The epitaph then reads:

No friendly hand could rescue or could save The much lov’d victim from a distant grave.

Cenotaphs within the Cemetery

We tend to think of empty graves decorated with cenotaphs as being for people buried far away, but we might apply the concept to intra-cemetery moves as well. I mentioned Thomas Hilton, first husband of Rachel Shaw, above as likely being buried somewhere at Eastern Cemetery, just not with his wife. Additionally, three of Bartlett Adams’ children, two sisters in the Owens family, a girl named Cornelia Rogers, and another girl named Abigail Babcock all have two burial listings at Eastern Cemetery. Each was assigned a plot (and stones are found on them) but they also are listed on tomb rosters.

I believe that when these children died, they were buried in the older section of the cemetery in their own graves (and with stones). Later, their families purchased family tombs in the newer section and they had their kids’ names inscribed on the larger tomb monuments (thus the “burial” record), even if they didn’t move the remains into the tombs. Though I left these kids off the intentional cenotaphs roster, I mention them here for further consideration.

3 Honorable Mention Cenotaphs

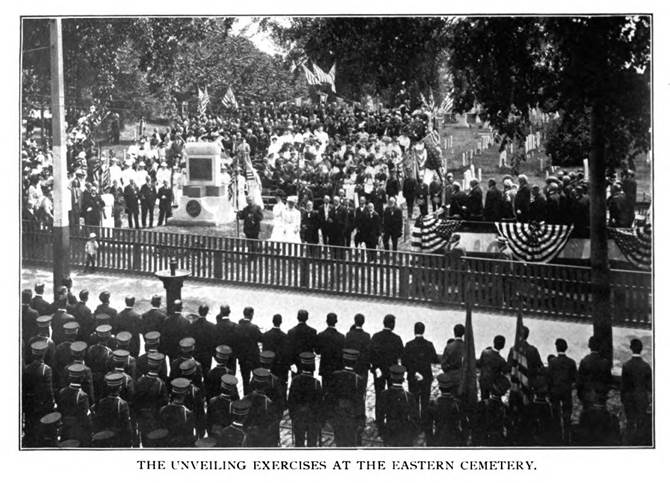

The most grand cenotaph at the cemetery is for Alonzo Stinson, who died—and was laid to rest—at Bull Run, Virginia. He was the first Portlander to fall in the Civil War.10 The monument was erected 50+ years later to great fanfare in the front corner of the cemetery where Congress and Mountfort Streets meet. In this image of the monument’s unveiling celebration in 1908, the Stinson monument can be seen center left.

Figure 25. 1908 Celebration in Eastern Cemetery

It is an impressive monument in its own right and a wonderful memorial to Stinson. But its placement came only after the remains of the African Americans originally laid to rest in that patch were removed and put in a mass grave nearby to make room for it.

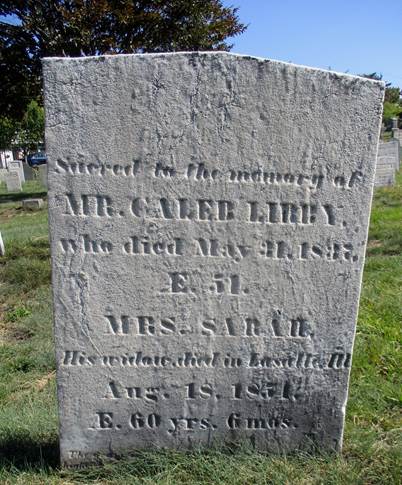

Figure 26. Gravestone for Caleb Libby

Of the 85 intentional cenotaphs at Eastern Cemetery, 84 are for males. Sarah Libby is the only female to be so memorialized. She lost her husband, Caleb Libby in 1837 and then headed to the midwest. A marker was put on his grave in Section A, Row 8, Grave 10. She died in La Salle, Illinois in 1854 at the age of 60. Back home in Portland, her family had her name inscribed on Caleb’s stone, for it reads “His widow died in La Salle, Ill. Aug. 18, 1854.” Sarah was buried at the Oakwood Cemetery in La Salle and has a marker there on her grave, so her memorial at Eastern Cemetery, a secondary cenotaph, is quite unique.

Figure 27. Monument for Bill Jordan (Photo by Dave Smith)

And finally, we end where I began, talking about Bill Jordan, a historian of the cemetery and author of two of the primary sources used for this research. Tomb 80 was in his family’s possession for many years, having changed hands from the Mussey family around 1870. It was Bill’s stated desire to become the last person buried at Eastern Cemetery, but upon his death in 2015 his family had his remains interred at Forest City in South Portland. They installed a white marble bench on the Eastern Cemetery tomb, to encourage visitors to sit and appreciate the history and beauty that the cemetery offers. The bench was installed in 2016 and is inscribed with Bill’s dates of birth and death as well as “In honor of...” an “Educator, Antiquarian, Bibliophile, Historian.” Though not of a typical gravemarker shape, it serves well as a modern-day cenotaph.

Final Thoughts

While the roster of cenotaphs is solid, I suspect there are more at Eastern Cemetery that have yet to surface, particularly among the 700 records of removals and the 225 records of veterans. The Spirits Alive conservation crew continues to unearth stones that have been subsumed by the sod over many years. And as more records appear for burials at other cemeteries, our list of unintentional cenotaphs should grow.

I thank Larry Glatz for setting me on this journey. He, Herb Adams, and Janet Joyce helped me sort out the list of men who died in the wreck of the Dash. I thank Penelope Hamblin for reviewing the veterans roster, and those named below for posting photos on the Find A Grave website I used in this paper. Martha Zimicki and Holly Doggett are owed a big thank you for the fine work they and their teams have done on the Spirits Alive transcription project. That work continues.

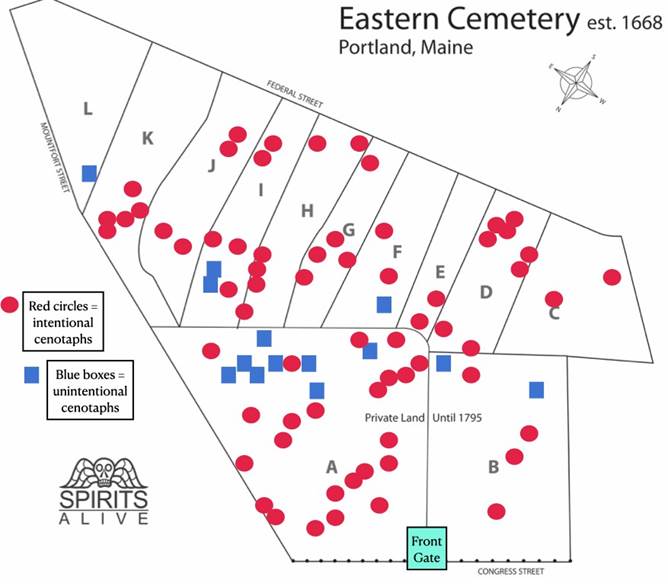

Appendix A - Cenotaphs Plot Map

Figure 28

Appendix B - Transcription Form (2 pages)

Figure 29

Figure 30

Table A - Intentional Cenotaphs

| Note Link | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alden | Capt. John Jr. | 1833 | 20 | A-3-18 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Alden | Franklin | 1820 | 17 | A-3-18 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Bailey (Bayley) (Bagley) | Hudson | 1798 | 48 | B - 10 - 13 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Baker | Capt. William | 1811 | ? | A - 3 - 22 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Bradbury | Francis | 1851 | 21 | A - 15 - 4 | died in New Mexico | secondary | Note |

| Bradford | Henry C. | 1840 | 23 | A - 8 - 18 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Bradford | Alexander | 1826 | 18 | B - 2 - 1 | died in Virginia | secondary | Note |

| Bradford | Nathaniel Jr. | 1825 | 21 | B - 2 - 1 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Briggs | Abner | 1839 | 17 | not known | died at sea | primary | Note |

| Carter | George Henry | 1823 | 18 | K - 133 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Chase | Capt. Benjamin Tappan | 1821 | 35 | H - 17 | died at sea | primary | Note |

| Chase | Capt. Amos T. | 1840 | 29 | H - 20 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Cobb | Smith Woodward | 1815 | 22 | D - 129 | lost at sea (Dash?) | primary | Note |

| Cobb | Daniel | 1810 | 21 | D - 129 | died in St. Barth’s | primary | Note |

| Cobb | William | 1805 | 21 | D - 129 | died at sea | primary | Note |

| Crosby | Capt. Watson C. | 1775 | ? | F - 45 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Cushing | Jacob | 1816 | ? | I - 15 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Day | Joseph | 1851 | 40 | A - Tomb 26 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Dodge | Israel | 1812 | 18 | J - 46 | lost at sea (Dart) | secondary | Note |

| Fenley | Capt. Benjamin W. | 1854 | 28 | J - 134 | died at sea | primary | Note |

| Green | Henry Jr. | 1809 | 23 | A - 6 - 10 | died at sea | primary | Note |

| Hall | Aaron | 1828 | 20 | I - 121 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Hall | Joel | 1837 | 18 | A - 3 - 10 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Ham | Tobias | 1821 | 18 | I - 91 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Harding | Ariston | 1806 | 26 | E - 53 | died in Brazil | secondary | Note |

| Harding | Daniel | 1811 | 21 | E - 53 | died in West Indies | secondary | Note |

| Harding | Job | 1810 | 27 | E - 53 | died abroad | secondary | Note |

| Harding | Stephen Jr. | 1823 | 31 | E - 53 | died in Maryland | secondary | Note |

| Herrick | Dr. Martin | 1820 | 73 | A - 21 - 7 | died Massachusetts | secondary | Note |

| Hilton | Thomas | 1793 | 27 | J - 106 | Eastern Cemetery | secondary | Note |

| Hope | Robert A. | 1802 | infancy | I - 25 | died in Virginia | secondary | Note |

| Jordan | William Barnes, Jr. | 2015 | 88 | A - Tomb 80 | buried S. Portland | primary | Note |

| Knight | William W. | 1806 | 24 | F - 113 | died at sea | primary | Note |

| Knight | Capt. William W. | 1832 | 24 | A - 2 - 11 | died at sea | primary | Note |

| Lane | Columbus | 1805 | 3 months | K - 142 | died in Vermont | secondary | Note |

| Libby | Sarah | 1854 | 60 | A - 8 - 10 | died in Illinois | secondary | Note |

| Loring | Capt. George W. | 1847 | 24 | A - 90 (between tombs 83 & 84) | died at sea | primary | Note |

| Loring | Capt. Ignatius | 1805 | 49 | A - 4 - 3 | died in Grenada | secondary | Note |

| Lowell | Joseph H. | 1833 | 33 | K - 49 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Lowell | William | 1835 | 28 | K - 48 | died in Port Mahon | secondary | Note |

| Mason | Munroe C. | 1825 | 16 | A - 1 - 5 | lost at sea | primary | Note |

| McLellan | George | 1801 | 19 | H - 181 | died in Surinam | secondary | Note |

| McLellan | Plato | ? | ? | A - 24 - 28B | buried in Gorham, ME (?) | primary | Note |

| Montgomery | Thomas J. | 1854 | 30 | A - 24 - 21 | died in state of Washington | secondary | Note |

| Moody | Daniel S. | 1821 | 21 | G - 10 | died in Cuba | primary | Note |

| Moody | Edward | 1823 | 17 | G - 19 | died in Cuba | secondary | Note |

| Mountfort | John | 1815 | 19 | D - 35 | lost at sea (on the Dash) | secondary | Note |

| Mountfort | Isaac | 1809 | 21 | D - 38 | died in Cuba | secondary | Note |

| Morss | Joseph | 1810 | 20 | C - 225 | died at sea | primary | Note |

| Morss | Charles | 1811 | 20 | C - 225 | died in Guadeloupe | primary | Note |

| Paine | Alexander | 1818 | 29 | G - 42 | died in Guyana | primary | Note |

| Peterson | Hewett W. | 1842 | 23 | B - 8 - 31 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Poole | James M. | 1853 | 29 | A - 4 - 10 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Radford | Joseph B. | 1833 | 18 | A - 5 - 10 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Ramsey | William | 1819 | 18 | A - 17 - 11 | died in Haiti | primary | Note |

| Reynolds | Capt. James | 1837 | 26 | B - 6 - 7 | died in Louisiana | secondary | Note |

| Richards | George P. | 1849 | 17 | A - 16 - 6 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Roberts | George | 1815 | 42 | A - 13 - 5 | lost at sea (on the Dash?) | secondary | Note |

| Sawyer | Capt. John | 1831 | 48 | A - 11 - 14 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Sawyer | John (Jr.) | 1839 | 32 | A - 11 - 14 | died in Maine | secondary | Note |

| Shattuck | Cato | ? | ? | A - 24 - 28A | buried Gorham, ME (?) | primary | Note |

| Shaw | Capt. Benjamin | 1823 | 74 | H - 35 | died in Belize | secondary | Note |

| Shaw | Samuel | 1815 | 20 | H - 35 | lost at sea (on the Dash?) | secondary | Note |

| Shaw | John | 1837 | 24 | G - 132 | died in Guyana | secondary | Note |

| Shaw | Samuel | 1818 | ? | J - 106 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Sheafe | John | 1838 | 29 | C - 94 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Simmons | William | 1780 | 40 | E - 62 | died in Nova Scotia | secondary | Note |

| Simmons | Capt. William | ? | 24 | E - 62 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Small | Capt. Henry | 1825 | 55 | B - 11 - 11 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Smith | William Rufus | 1821 | 21 | H - 3 | died in Guadeloupe | primary | Note |

| Stinson | Alonzo | 1861 | 19 | A - 14 - 23 | died in Virginia | primary | Note |

| Strong | Capt. Robert | 1817 | 43 | K - 167 | died in Martinique | secondary | Note |

| Thrasher | Benjamin Franklin | 1860 | 40 | D - 46 | died in Cuba | primary | Note |

| Thrasher | Benjamin | 1855 | 64 | D - 47 | died in Cuba | primary | Note |

| Todd | Samuel | 1829 | 51 | I - 27 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Tukey | Henry | 1821 | 26 | G - 33 | died in Indonesia | secondary | Note |

| Veazie | Isaac Jones | 1809 | 22 | J - 108 | died in St. Barth’s | secondary | Note |

| Veazie | John (Jr.) | 1800 | 23 | J - 108 | died in Guyana | secondary | Note |

| Veazie | Stephen | 1814 | 35 | J - 108 | lost at sea (on the Dash) | secondary | Note |

| Wadsworth | Lt. Henry | 1804 | 20 | H - 13 | died in Libya | primary | Note |

| Weeks | Capt. Joseph | 1797 | 35 | D - 146 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

| Weeks | Daniel | 1815 | 27 | D - 146 | lost at sea (on the Dash) | secondary | Note |

| Weeks | Capt. James | 1809 | 21 | D - 153 | died at sea | primary | Note |

| Williams | Capt. John, Jr | 1845 | 41 | A - Tomb 14 | lost at sea | secondary | Note |

| Williams | Capt. Robert | 1833 | 25 | A - Tomb 14 | died at sea | secondary | Note |

Notes: Intentional Cenotaphs

Capt. John Jr. & Franklin Alden – The marble stone at this location marks the grave of 62-year-old Capt. John Alden, who died in 1833. Though eroding, we can see below his name “Also...” then the names of Capt. John Jr. (“died at sea”) and Franklin (who “was lost at sea.”) In his book, Jordan excluded John Jr. but instead named “Joshua,” then in the ROI he put all three names but had no date or age for Joshua. The transcription form confirms that the stone names only Capt. John Jr. and Franklin, so Jordan’s use of Joshua in the book and ROI appears to be an error. (Note: After publication of this paper, the marker was lifted from the ground to be cleaned and repaired, revealing Joshua’s name and age of 27.) Back to John | Back to Franklin

Hudson Bailey – The Cumberland County, Maine archives state: "He sailed from Portland as mate in the vessel Snow Maria with his father as captain. The vessel was captured and condemned as a valuable prize. The captain died about that time, and Hudson, the son, was washed overboard and drowned...." The slate marker is in good shape and confirms Hudson “drowned at sea.” It then names Hudson’s wife Sally, who died in 1838. It is more of a design and style of an 1838 marker than a 1798 one. Originally inscribed as Bagley, the carver made the G into a Y as best as he could. Back to Hudson

Capt. William Baker – An eroded, broken, fallen marble stone is found at the plot. The ROI indicates it was a shared marker for the captain and his widow, Abigail, who died in 1871 at age 92. It is likely that the stone was placed on her grave and secondarily memorialized William who had died 60 years earlier. No vital records or newspaper accounting of his death are found. Still, Jordan’s book includes the stone inscription of “Lost at sea.” Back to William

Francis Bradbury – This is a shared marble marker for parents Alden & Caroline Bradbury and three children, including Francis, who is listed last on the marker. The inscription tells us that he died in New Mexico in 1851 at age 21. He was at the time serving the US military as a private. Further details of his death aren’t found in newspapers or other sources. Back to Francis

Henry Bradford – This is a shared marble marker for Henry and his sister Harriet, who died in 1847 at age 27. She is named first, so the stone was placed at the time of her death, and Henry’s death, noted on the stone as “Lost on the steamer Lexington,” follows. According to a Boston newspaper, Henry had lived in Boston for a while then worked in Jamaica for three years. While journeying home on the Lexington from New Orleans to New York, he “met his destruction” when the ship’s cargo of baled cotton caught fire and spread throughout the vessel. Only one survivor was known; 150 others perished. Back to Henry

Alexander Bradford – There is a shared slate marker in good readable condition naming the family patriarch, Nathaniel Bradford Sr. and three sons. He is also memorialized at Evergreen Cemetery, so he is listed on Table B (“Unintentional Cenotaphs”). Two of his three sons died while away from home. Alexander’s inscription on this marker reads “died at Va…” He is not memorialized on the monument at Evergreen or at a cemetery in Virginia, though it is likely he was buried there when he died in 1826. No newspaper accountings of his death are found. The Maine VR of death erroneously notes that he died in Maine, but the source is “from tombstone” which clearly notes Virginia. Back to Alexander

Nathaniel Bradford, Jr. – Nathaniel Jr.’s inscription on this marker reads “died at sea.” He is not memorialized on the monument at Evergreen. The newspapers reported that Nathaniel was aboard the brig Fame, traveling from Havana to Providence, when he died in 1825. Back to Nathaniel

Abner Briggs – We find no stone or plot location for Abner Briggs. While at sea aboard the barque Nautilus in the spring of 1839, Abner fell from the fore yard-arm to the ship’s deck and died of his injuries. The Nautilus was en route to Le Havre (France) from Charleston, South Carolina, and so Abner would have been buried at sea. The fact that a burial record exists for Eastern Cemetery suggests that at one time the family had memorialized Abner on a stone that has since gone missing. Back to Abner

George Henry Carter – There is a shared slate marker on this plot for George Henry Carter and his brother George Edward Carter, who was born the same year that George Henry died. The younger George lived only four years. George Henry is listed first on the marker and the words “died at sea” are on the stone. No newspapers are found to detail the circumstances of his death. Back to George

Capt. Benjamin Tappan Chase – An eroded broken marble marker is all that is left on this plot. Family members are in adjacent plots. We assume that the captain was buried at sea; Jordan’s book includes the original inscription of “Died of yellow fever on voyage from Cuba.” Back to Benjamin

Amos T. Chase – There is a shared stone at this plot for Amos and his wife Cynthia, who died 3 years before him. The Find A Grave listing refers to the stone as a cenotaph for him and a newspaper clipping accompanies his listing which confirms that he was one of four who died during the wreck of the Tariff off of Scituate, Massachusetts. It’s unclear if his body was lost or recovered. Back to Amos

Daniel, Smith Woodward, & William Cobb – A shared slate marker in good condition is found at this plot for three sons who died at sea/abroad. The epitaph on the stone tells the story: “Erected in memory of three sons of Daniel and Nabby Cobb. WILLIAM, who died at sea, Jan. 1805, AEt. 21; DANIEL at St. Bartholomews, Nov. 28, 1810. AEt. 21; SMITH WOODWARD, lost at Sea. Jan. 1815. AEt. 22. Far from their native land, They perished in the drowning deep. Without a friend to stretch the hand, And none their early fate to weep.” Smith Woodward Cobb may well have been a crewman on the privateer Dash. Back to Daniel Back to Smith Back to William

Capt. Watson C. Crosby – This plot has a slate stone carved by Bartlett Adams. It marks the grave of Abigail Crosby, who died in 1810 at age 73. Her inscription reads: In memory of Abigail Crosby, relict of Capt. Watson Crosby (who was lost at sea in the Autumn of 1775.)... Back to Watson

Jacob Cushing – A shared marble marker for four members of the Cushing family is found on this lot. The slab is eroding but some inscription is decipherable. The top names are patriarch Loring and matriarch Lydia Cushing. Mary (presumed daughter) is next, and Jacob (presumed son) is at the bottom of the marker, noting that he died at sea in February of 1816. A check of the newspapers and other sources does not allow for any more details on him or the exact circumstances of his death at sea. Back to Jacob

Joseph Day – Twenty-two people from four families are listed at this tomb, including Joseph Day and his parents. The ledger is eroded and not easily read, but newspapers confirm his death date. There’s also a suggestion made that he took his own life (perhaps due to failing health). He was aboard the Atlantic and five days out to sea when he died. The newspaper accounts are entitled “Death of a Boston Merchant” and refer to him as a lawyer and merchant “of Boston” and that Boston was “the place of his birth and education.” He was described as having been established in Cuba and then Boston, with no mention of Portland. Yet we find him in the Portland directories of 1834 & 1837 as a merchant at Ezekiel Day’s business. The newspaper reported that his remains were being returned to Boston, with no mention of further transfer to Portland. Back to Joseph

Israel Dodge – This is a shared marble marker for Sally (Sarah) Dodge, who died at age 75 in 1843, and her son Israel, who died at age 18. His inscription cannot be seen in the Find A Grave photo, but was found below grade during the SA transcription project. It reads, “Lost in the Privateer Dart, aged 18 yrs.” The Dart was active in 1812 along the Maine coast and so his year of death is inferred. No newspaper accounts of Israel’s death are found to nail down details, but the fact that he was “lost” suggests this is a cenotaph for him and a true grave marker for his mother. Back to Israel

Capt. Benjamin W. Fenley – Capt. Fenley is memorialized on a large white marble stone decorated with an anchor. The stone is eroded and difficult to read, but Jordan’s records note that the inscription noted “buried at sea.” The newspaper accounting of his death noted that he was of Boston, formerly of Portland, and that he had died on his passage from Aspinwall (today, Colon, Panama) Back to Benjamin

Henry J. Green – A slate marker in good, readable condition is at this plot and names only Henry, who “died on his passage from Havana” in September of 1809. The newspaper tribute noted that he was aboard the brig Diligence when he died. The paper named three other young men who also died on that voyage and lamented how many local boys had perished at sea in the past two years. Back to Henry

Aaron Hall – A slate marker in good, readable condition is at this plot, for four sons of Peter & Ann Hall. The top name is Stillman, who died in 1834 at age 14; below him are his three brothers in the order of their deaths, the last being Aaron in 1828. The inscription for him reads “died at sea, June 13, 1828.” The newspaper notes that he died “on the brig Warren, on her passage from Matanzas [Cuba] to Norfolk, very suddenly, age 18 years, a native of Portland.” A family monument at lot A - 3 - 10 also lists Aaron. Back to Aaron

Joel Hall – Presumed to the brother of Aaron, since they are listed together on the Hall family monument on this plot. He does not have his own marker as Aaron does. The Portland vital records note his death on January 4, 1838, while the inscription on the marker is 1837 and it reads “died at sea.” No newspaper accounts of his death are found, so we do not know other details. Back to Joel

Tobias Ham – A very nice and unusual slate marker from the Adams shop is on this plot. It’s decorated with an urn and 8 willow trees, and the top line reads “In memory of four sons of Jacob & Mary Ham.” Tobias’ three brothers are listed before him with death dates 1803 to 1817. Tobias is last on the list, with an inscription that reads “died at sea Aug 10, 1821.” The newspaper of the day noted that he was on his passage from Havana to Portland aboard the brig Edwin when he died. Back to Tobias

Ariston Harding – The shared stone at this plot is for the family patriarch, Dr. Stephen Harding, who died in 1823 at age 62. The marble has delaminated, so the majority of the inscription has been lost forever. A footstone exists and is in Bartlett Adam’s hand. Ariston’s death in 1806 was noted in an 1807 paper indicating place of death being “the Brazils.” Back to Ariston

Daniel Harding – Daniel’s name is on the stone and his death in 1811 was noted in the newspaper as having occurred in the “West Indies.” Back to Daniel

Job Harding – No notice is found for Job’s death in 1810, though Jordan noted in his book that all four men had “died abroad.” Back to Job

Stephen Harding, Jr. – Stephen Jr.’s death was noted in the paper to have resulted from “the prevailing fever” in Baltimore in 1823. Back to Stephen

Dr. Martin Herrick – There is an eroding white marble marker on this plot, for Sarah Wright Herrick, who died in 1843. She outlived her husband by nearly 25 years. He died in Lynnfield Massachusetts and has a stone at the Old Burying Ground there. Since his name and death date follow Sarah’s confirms the marker is her gravestone and he is named for the familial relationship. Back to Martin

Thomas Hilton – This marble marker is for Rachel (Veazie) Shaw, who died 1849 at age 79. She had far outlived her two husbands, Thomas Hilton (died 1793) and Samuel Shaw (died 1818). The stone has been restored by the SA conservation crew. Below Rachel’s name we find “Husbands of the deceased.” First is Thomas Hilton. The newspaper said that he was an exemplary individual, “But alas! Not all our care eludes the gloomy grave.” The stone is of a design that was made in the mid-1800s not late 1700s. Further, this stone rests on a single plot for one body. The adjoining plots are taken by other members of the Veazie family. While Thomas may be buried somewhere at Eastern, it is not at this plot. Back to Thomas

Robert Hope – This small shared slate marker was carved by Robert Hope (of the Bartlett Adams shop) for his two sons, one of whom died in Portland in 1806 and is buried at Eastern. The slate serves as a cenotaph for Robert Jr., who died in Virginia in 1802. Hope worked in the Adams shop for just a couple of years in the 1805–1808 window. Back to Robert

William Barnes Jordan, Jr. – Bill Jordan was author of the Eastern Cemetery book and ROI used for research. Tomb 80 was in his family’s possession since 1870. It was Bill’s stated desire to become the last person buried at Eastern Cemetery, but upon his death in 2015 his family had his remains interred at Forest City in South Portland. They arranged to have a white marble bench installed on the tomb to encourage others to appreciate the history and beauty that the cemetery offers. The bench was installed in 2016 and is inscribed with Bill’s dates of birth and death. Though not a typical gravemarker, it serves well as a modern-day cenotaph. Back to William

William W. Knight – A very nice slate marker from the Adams shop is on this plot. It is in a line of about a dozen stones for the Knight family. The stone confirms that William “Died on his passage from St. Bartholomew’s to Portland.” Back to William

Capt. William W. Knight – An eroded white marble stone is found at the plot. It is partially readable and it’s evident that it memorializes only Capt. William. The stone confirms that he “Drowned on his passage from Portland to Havana.” No newspaper notice of his death is found. Back to William

Columbus Lane – There is a shared slate marker on this plot for the “Two sons of Capt. Joseph and Gratey Lane who died in 1813 and 1819. It wasn’t until the SA transcription project that we discovered this marker names one more, Columbus, who died in Vermont in 1805 at 3 months. No gravemarker is known for him in Vermont, and he was not included in Jordan’s burial records. Back to Columbus

Sarah Libby – Sarah Libby lost her husband Caleb in 1837 and headed to the midwest, where she died in 1854 at age 60. The shared gravemarker at Eastern Cemetery names Caleb first, and then under her name we find “his widow died in La Salle Ill, Aug. 18, 1854.” There is a find-a-grave listing for her at Oakwood Cemetery in La Salle, so this is presumed to be a cenotaph for her. Back to Sarah

Capt. George W. Loring – Capt. George W. Loring was one of many children of George and Lucy Loring. He was master of the Boston-based ship Eliza Warwick and died at sea while on a journey from New York to Liverpool. In January 1847, a tremendous storm produced a great wave that swept him off the deck of the ship. The heavily-damaged ship was able to reach Liverpool. There is a very interesting newspaper clipping describing a girl who dreamt of his death at the time it occurred.

George’s parents are at Evergreen Cemetery, but a half-dozen of his siblings who died young remain in graves at Eastern Cemetery, decorated with modest gravemarkers. Oddly, George’s large white marble obelisk, set on a granite base, has eluded prior researchers, as his name is not found on the burial rosters in Jordan’s book or the accompanying Record of Interments. Back to George

Capt. Ignatius Loring – This is a shared marker in the style of 1830s slates, with the widow of Capt. Ignatius named first (Abigail, who died 1835). The captain is named below her and the inscription confirms his death occurred in Grenada. No newspaper accounts found. Back to Ignatius

Joseph H. Lowell – This is a shared marker for Joseph’s father Enoch, who died in 1832 at age 66. It’s a slate from the Ilsley-Thompson shop and in good readable condition. Below Enoch we find Joseph’s inscription “Drowned on his passage from Matanzas to Boston. (Cuba).” He died in 1833 as second mate on the brig Florida. A newspaper clipping details Joseph’s death at sea as well. Back to Joseph

William Lowell – Younger brother of Joseph H. This is another shared marker made of slate and in good readable condition. William’s mother is listed first; she died in 1845 at age 75. William’s name is at the bottom of the marker with the words “Died at Port Mahon.” This might be Delaware but could be Spain. No newspaper clipping is found to provide further details. Back to William

Munroe C. Mason – According to the newspaper, Munroe Mason fell from aloft aboard the brig Oxford, while at sea. He is said to have struck some part of the vessel while falling into the water. A line was thrown to him but he did not reach for it, and when they lowered a boat to the water to retrieve him, Munroe went under and was not seen again. The large marble marker on this plot is too eroded to read, but it appears to have had a lengthy inscription. Whether it was the story of his death, a shared marker for other family members, or a long epitaph is unknown. A more modern granite marker within a family lot at Oak Grove Cemetery in Malden, Massachusetts, lists Munroe Mason and “lost at sea” along with his brother (presumed) Frederic Mason and “died at sea.” Back to Munroe

George McClellan – This is a shared marker with George’s father Capt. William (named first), who died in 1815. It’s a purple slate in the style of markers from the mid-1800s, the surface of which is flaking (but still readable). Under the Capt.’s inscription we find the details that George “Died in Surinam” which is on the north coast of South America. No newspaper listing found. Back to George

Plato McClellan – After Jordan’s book was published, so not in the burial records, a new veteran’s marker was placed in the African American section of the cemetery, honoring this formerly enslaved person who served in the American Revolution. From historian Larry Glatz: “The Plato McClellan case is interesting. I’m pretty sure he died in Gorham and was buried there—perhaps on the property of the McClellan family, where he lived. I’m not really sure how this stone got to Eastern Cemetery.” Back to Plato

Thomas J. Montgomery – A badly eroded marble marker is on this plot, memorializing Dr. Nathaniel Montgomery, who died 1857. Secondary on this marker we can find the inscription for his son Thomas J., who was a captain in the 4th United States Infantry and who had died in Washington state three years earlier. He was originally buried in the Fort Steilacoom Cemetery in Washington but later removed to the San Francisco National Cemetery, where a veteran’s marker is found for him today. Back to Thomas

Daniel S. Moody – There is a slate marker in good condition for Daniel on this plot, within a long line of others from the Moody family. The inscription reads, “Died at Havana.” The epitaph confirms that this is a cenotaph, since it reads, “No friendly hand could rescue or could save, the much loved victim from a distant grave.” Back to Daniel

Edward Moody – This is a shared slate marker in good condition for Edward and his father William (primary on the stone). William died in 1821. Just two years later, his son Edward died in Havana. There is a long line of others from the Moody family in this section. The inscription reads, “Edward, son of William & Rachel Moody, died at Havana Aug. 27, 1823; aged 17 years.” The newspaper reported that Edward was aboard the brig Herald and that he was the youngest son of the late William and Rachel Moody. Back to Edward

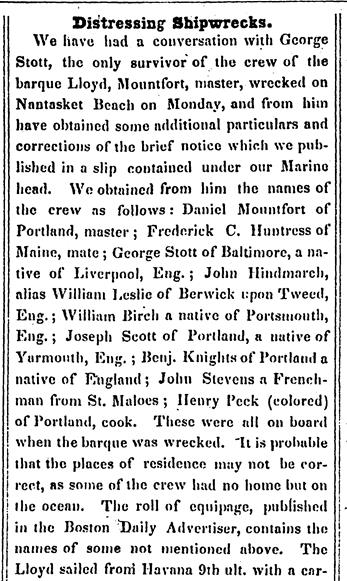

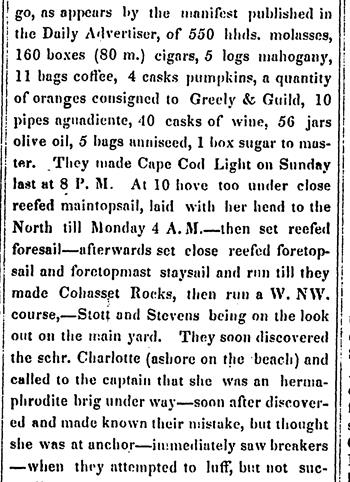

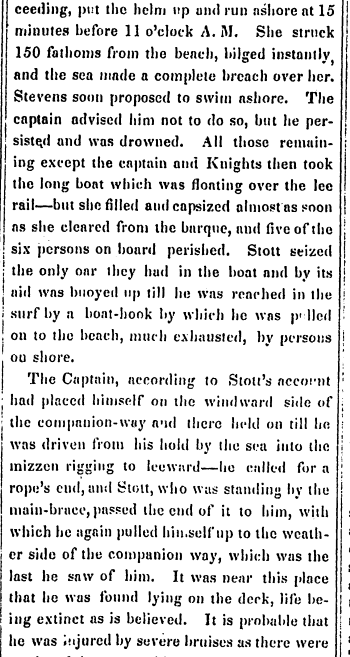

John Mountfort – This is a shared marker, memorializing a mother and two sons. Elizabeth (Ilsley) Mountfort died in 1852; her husband Daniel’s stone is immediately beside hers at D - 36. He died at age 60 in 1822. Under her name we find “Sons of Daniel and Elizabeth.” First is John, with “Lost on board Brig Dash, 1815.” Details are found in the paper under “The Dash and the Dart,” and this is a confirmed cenotaph. Also listed is Daniel Mountfort Jr., who died in 1839 in the wreck of the Lloyd off Massachusetts. His body was recovered and returned to Portland for burial (as confirmed by the newspapers of the time). Back to John

Isaac Mountfort – There is a shared stone at this plot for Isaac and his brother William, two more sons of Daniel Sr. and Elizabeth (Ilsley) Mountfort. It’s a slate in good, readable condition. William died in 1824 at age 24 and is listed first. Below him we find Isaac’s inscription and “died at Havana.” No newspapers are found to detail circumstances of his death. Back to Isaac

Joseph Morss – A small slate marker in fair condition (carved by Abel Davis while in the shop of Bartlett Adams) memorializes two sons of Nathaniel & Phebe Morss. They died just a year apart, Joseph “died at sea” in 1810. No newspaper found to confirm details. Back to Joseph

Charles Morss – A newspaper detailed Charles’ death in 1811. There was a notice that named him as “the only child of an affected widow” and that is true given his brother’s death the year before. On the marker is “died at Point Petre, G.” which is in Guadeloupe. Back to Charles

Alexander Paine – There is a slate marker in good condition on this plot, carved by Elias Washburn. The inscription notes that he “died in Demarara.” Demarara is along the north shore of South America (the Guyanas). Given the distance back to Portland, he was surely buried in South America or at sea. One newspaper said he was “of Westbrook” and another said he was “of Portland.” Back to Alexander

Hewitt W. Peterson – A shared white marble marker in eroded but readable condition stands on this plot. Capt. Daniel died 1856 at 73 and is listed first, below him we find “Hewitt W., only son of…” and “lost at sea.” No other details are found in newspapers. Back to Hewitt

James M. Poole – There is a pedestal monument on this lot, and James’ name and date are inscribed, along with “lost at sea.” The transcription form confirms his in the only name inscribed on the south-facing panel. The monument was erected for his father James (died 1868) and his name is on another panel. No newspaper accounting of James, Jr’s death at sea is found. Back to James

Joseph B. Radford – There is a shared stone at this plot. The white marble is eroding but somewhat readable. The stone lists Joseph’s father first, who died in 1836. Then, below a decorative flourish, we find his sister Frances who died 1821 and then Joseph. A newspaper notice from July 1833 notes only that Joseph died at sea... no other details included. Back to Joseph

William Ramsey – This is a terrific shared marker for William and his sister Ann Louisa. It is slate, in very good condition and carved by Elias Washburn. The stone was placed here for William, since his name is first and the lettering is that of Elias who was in the Adams shop until about 1821. Many years later (c. 1842 when Ann died) another carver added her name to the stone. The lettering is quite different for both names. The inscription confirms he died in Port-au-Prince, and the epitaph confirms this as a cenotaph, as it reads “Far from your friends dear child your body doth lie; May Christ be your friend and keep your soul on high” Back to William

Capt. James Reynolds – This is white marble pedestal monument inscribed on three sides. Eight members of the family are listed. The pedestal is cracked where James’ inscription is, but a faint “Died in New Orleans” can be read on the eroding surface. No newspaper notice of death is found for him. Most likely he was buried in Louisiana. Back to James

George P. Richards – A restored white marble marker is found for George and his sister Sarah Jane, who died a year after him in 1850 at age 14. Their father John K. died in 1837 and has his own marker a few rows away. No further details are found in the newspapers for George, but the inscription under his name is clear: “died at sea.” The decoration features two broken buds, representing these two children. Jordan’s burial record for Sarah Jane says she died in Boston. This fits what we know about her mother, who remarried after John K. died in 1837 and relocated to Boston. If Sarah Jane died in Boston where her mother lived, why was she brought back to Portland for burial? The stone may serve as her true gravemarker, but is a cenotaph for her brother. Back to George

George Roberts – Though only a remnant of the original marble stone is found on this plot, it originally memorialized George and his wife Hannah, who outlived him by 40 years. The marker was likely placed when she died in 1855 and his name was secondarily mentioned. Jordan’s book noted the quoted lettering from the marker as “Lost in the Dash.” More details are found in this paper under the heading “The Dash and the Dart.” Back to George

Capt. John Sawyer – There is a shared marble marker on this plot, for the captain and his son. The captain’s inscription is first and notes that he “perished at sea.” He was in command of the brig Superb of Portland at the time of his death. There is another marker found at Evergreen Cemetery for him which may be a cenotaph. Back to John

John Sawyer, Jr. – John Jr.’s inscription is second, stating that he died in 1839 “at Belfast” at age 33. The newspaper notice of his death says that he was a resident of Belfast, Maine for over a year, working as the landlord of the American House. His death was caused by a fever of 7 weeks duration. No stone is known for him in Belfast, so it is possible that his remains were brought to Portland for burial, resulting in the placement of this shared marker with his father. Back to John Jr.

Cato Shattuck – After Jordan’s book was published, so not in the burial records, a new veteran’s marker was placed in the African American section of the cemetery, honoring this formerly enslaved person who served in the American Revolution. From historian Larry Glatz: “The Cato Shattuck case is quite interesting. He died in Westbrook while traveling from Portland back to his home—or the home of his employer—in Gorham. The place was off the Fort Hill Road, not far from the North Street Cemetery. I once made a plea to the Gorham VFW to seek the relocation of Shattuck’s military marker from Eastern Cemetery to the North Street Cemetery to better reflect his personal associations. But I got nowhere. The folks there didn’t want to ’disturb’ an already-set marker. I’m not really sure how this stone got to Eastern Cemetery.” Back to Cato

Capt. Benjamin Shaw – A single slate marker in good readable condition—inscribed by Bartlett Adams—is found on this lot. It memorializes eight members of the family, all of whom died in 1823 or earlier. Two of the eight died while abroad. The patriarch Benjamin’s inscription notes that he “died in Baliz, Honduras” (Belize) in 1823 and it is clear based on his placement on the marker that this is his cenotaph. Benjamin’s newspaper notice of death says that he died “in the Bay of Honduras.” Back to Benjamin